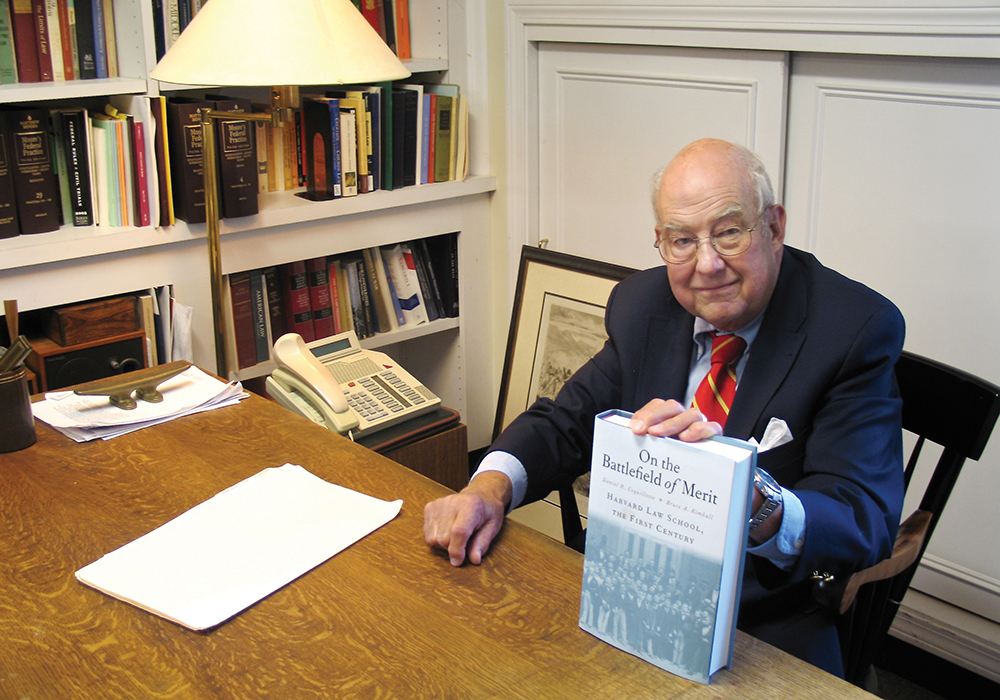

“If you want to avoid the mistakes of the past, you’d better know what the past is,” says J. Donald Monan, SJ, University Professor Daniel Coquillette. He’s explaining the warts-and-all approach of The Battlefield of Merit, the first installment of a planned two-volume history of Harvard Law School. While published by Harvard’s own university press, the book, co-written by Coquillette and Bruce Kimball, a historian of education, devotes many pages to the great law school’s sins, especially its long entanglement with slavery, which began with its 1817 founding.

Harvard Law was established using money from a family of slave traders and plantation owners. Among them was slaveholder Isaac Royall, whose coat of arms—three bushels of wheat on a shield—later became the official seal of the law school. Since publication of The Battlefield of Merit, that seal has become the source of widely covered student protests demanding the offending symbol’s removal.

Also, during the law school’s first half-decade, Joseph Story, an early dean as well as a US Supreme Court justice, upheld the notorious Fugitive Slave Act in his opinion in Prigg v. Pennsylvania.

Harvard Law in its early years was competing not with other law schools but with traditional legal apprenticeship. Under Story, the school offered three things that students couldn’t get from apprenticeships, says Coquillette: It taught law from a national perspective, with courses on constitutional law and legal philosophy, subjects rarely covered in apprenticeships; it admitted students based on merit; and it styled itself a training ground for national leaders. “These three ideas are so powerful that they’re still the creed of Harvard Law School today,” says Coquillette, “as well as the creed of every elite law school in the country.”

In striving for national standing, though, Harvard Law recruited nationwide, and for years one-third of the student body came from the South, teeing up intramural debates between southern supporters of slavery and northern abolitionists.

“Seeing a man in chains on the streets of Massachusetts, that was too much.” —Daniel Coquillette

The bitterest debate came in 1854, when Edward Loring, a federal commissioner in Boston and also a Harvard Law lecturer, ruled against an escaped slave whose owner was suing for his return. Southern Harvard Law students formed a sort of honor guard, escorting the slave owner to and from the proceedings. At Loring’s first class after the ruling, “southern students stood and applauded, and northern students hissed,” says Coquillette. “Seeing a man in chains on the streets of Massachusetts, that was too much”—not only for students but also for Harvard’s overseers, who let Loring go at the end of the term. Still, the debates over slavery raged, lasting until war came and southern students departed, many to serve the Confederacy as government officials and military officers.

The law school’s great post-bellum leader, C.C. Langdell, like his predecessor Story, revolutionized legal education. Langdell introduced case method instruction, replacing old-fashioned treatises and recitations with casebooks and Socratic questioning. Langdell “talked about law as if it were a science,” says Coquillette. “He said, ‘We can dissect those cases the way you dissect a frog,’ ” deriving broad principles from a close acquaintance with the facts.

Langdell also made the school more meritocratic, demanding college degrees of applicants and introducing class rankings and written exams. On the other hand, he contravened his own meritocratic principles by refusing admission to women students—according to his theory, law is “unfit for the feminine mind”—and by casting a wary eye on applicants from Catholic institutions, including Boston College.

Despite a record that includes Langdell’s admissions policies and Story’s deplorable opinion in Prigg, Harvard Law, thanks in part to those two flawed men, has made lasting contributions to legal education, and to American history. Coquillette points to our 2012 presidential election, in which both candidates and the man who swore in the winner had Harvard Law degrees. “I think Joseph Story is laughing in his tomb,” muses Coquillette, “and saying, ‘I achieved what I set out to achieve.’”