She has decided the fate of an alleged Somalian pirate, forced the release of Guantánamo detainees, ruled that confessions obtained through torture from Rwandan murder suspects were inadmissible in court, and presided over AT&T’s doomed merger with T-Mobile. She created precedent on battered woman syndrome. She represented boxing promoter Don King in a tax fraud case. And she has promoted the rule of law in countries that desperately need it.

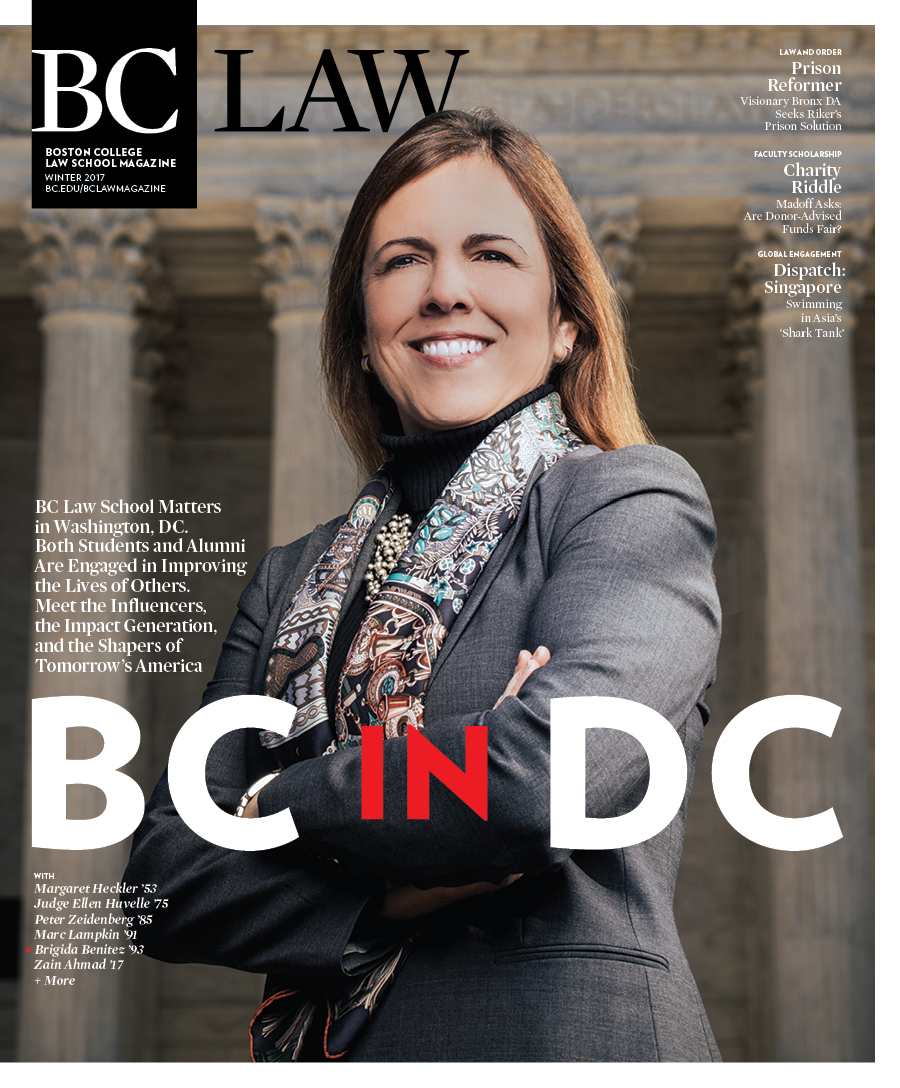

She is Ellen Segal Huvelle ’75, and these are just a few highlights of her forty-plus years in the law, more than nine of them as a judge for the Superior Court of the District of Columbia, and seventeen on the bench of the United States District for the District of Columbia.

Huvelle graduated from BC Law during a transformative time. The Civil Rights Movement was changing, the Women’s Movement emerging, the Vietnam War ending. About 20 percent of American law students were women. By 1977, only eight women had ever served in the federal judiciary. Today, women make up about a third of the judges in the federal courts. At a September 29, 2016, ceremony where the US District Court for the District of Columbia received Huvelle’s portrait, in attendance were more than four hundred of her colleagues, friends, and jurists—an influential swath of the capital’s best and brightest, including Associate Justice of the US Supreme Court Elena Kagan and former US Attorney General Eric Holder.

All this qualifies Huvelle as a trailblazer. But oddly, the word seems trite when applied to her, because the word that makes the most sense, that best captures her legacy, is simply:

Judge.

Huvelle grew up in Newton, Massachusetts, graduated from Wellesley College in 1970, and received a master’s in city planning from Yale School of Architecture in 1972. “In hindsight, city planning was too amorphous for me,” Huvelle says now. With her father, brother, and husband all lawyers, she saw the legal profession in sharper focus.

She clerked for a year for Chief Justice Edward Hennessey of the Massachusetts Supreme Judicial Court, and then in 1976, she and her husband Jeffrey (now a litigator at the DC firm Covington & Burling) moved to Washington, DC, where she joined the firm Williams & Connolly and eventually became the firm’s first female partner. There, as a young associate, she broke new legal ground when she was co-counsel defending a battered wife charged with murdering her husband. This was the late 1970s, and “back then, people certainly didn’t talk about battery, and I don’t know if there were any centers for battered women at all,” Huvelle says. Battered woman syndrome was emerging as a newly understood phenomenon, and the judge refused to admit expert testimony about it at trial. On appeal, Huvelle and her team argued that the trial judge’s refusal to admit that testimony was in error. They won.

“Ellen sensitively developed the defense of battered wife syndrome, which resulted in the publication by the DC Court of Appeals of the first appellate opinion in the country to recognize the admissibility of expert testimony on battered wife syndrome,” US District Court Judge Emmet Sullivan told the audience at the presentation of her portrait in September.

Huvelle also represented hotel magnate and tax-evader Leona Helmsley and boxing promoter Don King. “I always liked Don King,” she says. “He was one of the all-time great con men. He was very smart. He was self-educated and spent time in jail and had a wonderful sense of humor—he claimed that one day he woke up and God made his hair stand on end.”

In 1990, Huvelle was appointed Associate Judge of the DC Superior Court by President George H. W. Bush, and in 1999, she was recommended to President Bill Clinton for a seat on the US District Court for the District of Columbia by Congresswoman Eleanor Holmes Norton, who chose Huvelle from the three names submitted to her by her Judicial Nominating Commission. The commission vets applicants to the court and strives for diverse appointments. (Huvelle now serves as the court’s Senior Judge.) It took the Republican-controlled Senate more than two-hundred days to confirm her.

She spent her first year shoveling through an appalling backlog of cases. Huvelle “tackled her docket with a vengeance,” says her longtime law clerk Alison Grossman. “With the help of her law clerks…who once brought sleeping bags to the office, and her judicial assistant and a bevy of interns, she dug her way out and she never looked back,” Grossman told the audience at the portrait unveiling event. “As soon as she became chair of the Calendar Committee, she changed the way dockets are created for new judges so that no judge would ever again have a first year like hers.”

Huvelle gets a lot of good-natured ribbing from her colleagues for her legendary efficiency, but efficiency has a serious side. “The real beneficiaries are the litigants who appear before her,” Grossman says. “She sees no reason why a lawyer should spend hours questioning a witness when she can ask three critical questions and get the necessary information, saving everyone time and money. She sees no reason why work should stop just because there’s snow on the ground. And with no backlog, she and her clerks have the luxury of giving every motion and case the time and attention it deserves.”

Just as justice is never delayed in Huvelle’s courtroom, Grossman says, it is also never denied. “There was a time that she ordered the release of a pretrial detainee from the DC jail over the protest of the prosecutor after she learned from the detainee’s doctor that his death was imminent. There was a time she granted the petition of the youngest Guantánamo detainee and ordered the government to complete the transfer in twenty-one days, which seemed to her a perfectly reasonable amount of time. There was a time that she realized that an elderly defendant in a civil case was likely the actual victim of fraud by the plaintiff, and she promptly ordered that the plaintiff’s assets be frozen. She has on more than one occasion taken prosecutors to task for not properly exercising their discretion in bringing a case,” Grossman says.

Even the best judges, however, don’t spend twenty-six years on the bench without drawing criticism. Huvelle’s ruling in 2006 that the confessions of Rwandan defendants on trial for murder were inadmissible because they were derived through torture in Rwandan prisons led the Justice Department to drop the charges. In 2008, the same Rwandans applied for political asylum in the United States. A former investigator for the US Immigration and Naturalization Service was outraged. He told the Washington Times, “The fact that the judge tossed the confessions doesn’t make them innocent.”

And in the Somali pirate case, Huvelle was faced with the question of whether the defendant in a high-seas hostage-taking case was an advocate for the hostage-takers, or just a translator going between the pirates and the ship owner. Pending the trial, Huvelle twice ordered the defendant released from jail on the grounds that his lengthy imprisonment violated his constitutional rights. Twice, the appeals court reversed her. Ultimately, the jury ruled in 2013 that the defendant was not guilty of piracy.

Judges, in addition to their courtroom responsibilities, take on administrative work to further the functioning of their courts. Huvelle is no exception. She chairs the court’s Calendar and Case Management Committee, which makes assignments of cases among the twenty-one judges of the federal district court of DC. “Seems like a life appointment,” she confides in a nod toward her colleagues’ appreciation of her famed efficiency. On the Criminal Law Committee, she says, “we’ve looked at the question of the disparity of crack and powder cocaine and changed the law dramatically on that.” That committee has also addressed the release of prisoners who have committed non-violent drug crimes, sentencing guidelines and federal legislation involving criminal justice reform, and clemency and mass incarceration.

Supreme Court Chief Justice Roberts assigned Huvelle to the United States Judicial Panel on Multidistrict Litigation, which decides whether and where to consolidate civil actions pending in different federal districts. These cases tend to involve products liability, torts, pharmaceuticals, and similar matters that cross jurisdictions.

Huvelle has also dedicated herself to fostering the rule of law overseas, teaching courses in Tunisia and China, and in the US to lawyers and judges visiting from Algeria, South America, and Eastern Europe.

A fall down a staircase in 2014, when she was sixty-six, left Huvelle with a serious spinal injury. “I can walk, but poorly, and my right hand in particular is not very useful,” she says. “I carry less of a caseload, but probably comparable to most of the [senior judges] where I am and I have these other administrative responsibilities, so I keep busy,” she says.

As word spread about her injury, notes from well-wishers poured in. A lawyer accustomed to being put in his place in her courtroom wrote, “I hope you can get through this so you can tell me to sit down and not argue as you preside once more.”

A defendant whose fate she held in her hands sent this message: “For what it’s worth, I want you to know that I respected the decisions you made throughout my two trials. I did not agree with all of them, which you might recognize as a massive understatement since I am writing from prison. But I felt your decisions were arrived at honestly. You always seemed to think through the issues and reach conclusions you thought were required by the facts and the law.”

And this, from another defendant she sent to prison: “You approached my lawyer and asked how my girls were doing. I want you to know that meant a great deal to me, so much that I had trouble relaying that story to anyone without losing my composure. There were times when I felt lost in the criminal justice machine, that I lost my humanity, and was seen solely as a defendant and not a flesh and blood person. Your words at sentencing and your later inquiry to my lawyer demonstrate that you appreciated you had a real person’s fate in your hands. I am grateful for that.”

The generosity of spirit noted by those who have appeared in her court and among her wide Washington circle of friends and colleagues extends to Huvelle’s involvement with BC Law. Huvelle has served for many years, first on the Board of Overseers and more recently on the Dean’s Advisory Board. “Judge Huvelle’s love for the law school runs deep,” says Jessica Cashdan, executive director of campaign planning and associate dean of law school advancement. “She is generous in countless ways, from offering sage advice and identifying new opportunities for the school to hosting gatherings and facilitating introductions in Washington, DC, and across our community. She is always ready and willing to go the extra mile to help further the pursuits of our students, alumni, and the school.”

For her part, Huvelle says of her legacy: “I hope that I leave behind good cases, ones where defendants felt that they got a fair trial and that people respected me as a judge and as a human being.”

She continues, “At my level, it’s not as if I’m going to leave a particular case that will have major impacts on the law, but, hopefully, I have exercised my discretion fairly and properly, and I have contributed to the judiciary.”