“Who are the new guys?”

For law enforcement officers monitoring a basic brick home in the Bronx, most of what they were seeing on May 14, 2014 was familiar. Many of the same suspected drug dealers they’d been tracking throughout the northeast for months. The same squat dwelling surrounded by iron fences that appeared to serve as a base for a trafficking operation. Even the same gray Jeep that had replaced the car the team stopped in Connecticut the previous year, hoping for a large bust, but finding only a small sample of heroin.

Everything about the night’s surveillance looked normal, until the new guys emerged from the Jeep’s back seat. Clean-cut, fashionably dressed, and carrying backpacks, the two men who followed their driver into the house were completely unknown to investigators. Soon, more suspected drug dealers and traffickers began to converge on the property, further confirming that this wasn’t an ordinary spring night in New York.

Shortly after a meeting outside of the Bronx home that was captured on camera, the guys with the backpacks handed over eight kilograms of illegal drugs (four each of cocaine and heroin)—nearly eighteen pounds—exactly what their suppliers had promised. Investigators from the joint New York-based Drug Enforcement Task Force watching the house responded during the next two days with a multi-faceted surveillance detail that would take them to Queens, back to the Bronx, and all the way to Hartford, Connecticut. But the Task Force still had no idea who these new, clean-cut suspects were.

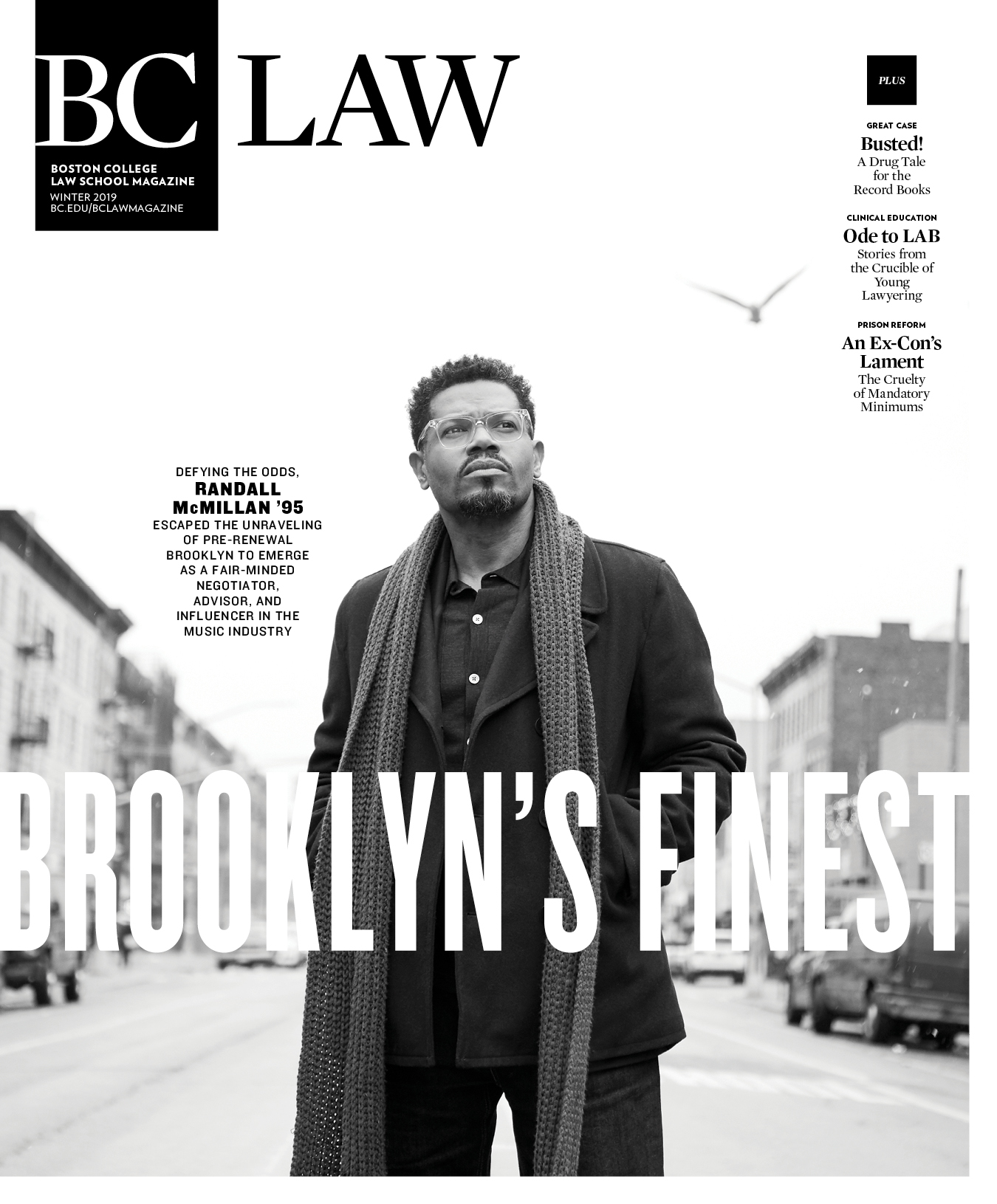

When law enforcement finally answered that question two months later, the information would help unravel a story that spanned three continents and two decades of diplomacy, plunging the Spanish Navy into an international scandal and putting sixteen men behind bars on both sides of the Atlantic. Andrés Torres ’08, an Assistant District Attorney in Manhattan assigned to the Office of the Special Narcotics Prosecutor for the City of New York, was a key part of it all.

The best way to understand why Torres was the right guy for this case requires—at some point along the way—digesting two seemingly unrelated items on the prosecutor’s résumé. By all appearances, they are merely chronological and topological waypoints. But suffice it to say for now that the convictions in The People of New York vs. seven drug-offender defendants, the Manhattan Supreme Court kingpin statute indictment and 2018 conviction of two extradited major-trafficker defendants, and the involvement of associated international tribunals, is also Torres’s story of optimal preparation meeting improbable opportunity.

STRANGER THAN FICTION

The full details of the Task Force’s 2014 criminal investigation into the stranger-than-fiction crime that unfolds below were culled from court documents, interviews, and law enforcement media advisories along with English and Spanish-language news reports.

Soon after the clean-cut newcomers’ evening arrival at the house in the Bronx back in May of 2014, the men, the backpacks, the gray Jeep (and a handful of other cars) were on the move again. Task Force (TF) members tracked the suspects to a club in Queens, where the contingent from the Bronx met with traffickers from Hartford into the early morning hours of May 15. As dawn approached, the newcomers traded their backpacks for $14,000 in cash. Their driver dropped them off near the Hudson River in Hell’s Kitchen, a West Side neighborhood in Midtown Manhattan best known for its nightlife and as home to the Manhattan Cruise Terminal, served by some of the world’s biggest cruise companies.

The whereabouts of the unidentified new guys after their drop-off were unknown, but TF surveillance teams stayed on top of the suspects they’d been surveilling all along. Taking down crews in the drug rackets was familiar territory for the elite group of crime-stoppers, made up of seasoned New York Police Department detectives, New York State Police troopers, and federal agents from the Drug Enforcement Administration, all operating in conjunction with the Office of the Special Narcotics Prosecutor for the City of New York, where Torres serves as Senior Supervising Attorney.

On May 16, they stopped and searched three different vehicles linked to the NYC traffickers—two of which they trailed to a Hartford location and another parked outside a second location in the Bronx. As officers entered into the suspects’ Connecticut destination, occupants inside furiously attempted to dump evidence down a sink. No sewer system could have handled the treasure trove. Between Hartford and the Bronx, investigators seized fifty-three pounds of heroin, approximately nine pounds of cocaine, $85,000 in cash, two military-style assault rifles, plus additional handguns and drug paraphernalia.

TF members waiting near the car parked at the second Bronx location then made their move, seizing more cocaine and the men inside the residential unit. With the dragnet tightening, additional members of the trafficking group turned themselves in. Another managed to avoid arrest and was later captured in the Dominican Republic after he attempted to ship a luxury Mercedes from the Bronx to his new hideout.

It was a good bust. By Memorial Day, after more than six months following the original lead, the Task Force had a bevy of men in custody and enough evidence for the Office of the Special Narcotics Prosecutor to build a strong case. The file landed on Andrés Torres’s desk.

The two stylish drug mules who vanished before sunrise on May 15 were still a mystery. Once law enforcement identified them during the ongoing investigation, however, those men and where they’d come from ensured that there would be nothing ordinary about the rest of the probe.

“We were able to get [certain] evidence immediately because of the strong law enforcement partnership that exists between the United States and Colombia now. That only happens when two countries are friends and have worked together for a long time. The legal field can be such a local thing, but when crime is globalized, you have to have lawyers who can function globally.” —Andrés Torres, Senior Supervising Attorney, Office of the Special Narcotics Prosecutor for the City Of New York

A SYMBOL OF GOODWILL

For weeks following the initial busts, law enforcement continued to pour over evidence as the Office of the Special Narcotics Prosecutor prepared criminal cases against the suspects already in custody. All the while, the Task Force was trying to pinpoint the pair still at-large, who hadn’t been part of the crew they’d been watching all along. The fact that the gray Jeep had had been within relatively close proximity to commercial piers in the afternoon hours of May 14 might have been a clue, but the Port Authority Bus Terminal, Penn Station, and the Lincoln Tunnel were all only a few blocks away as well.

What’s more, the only vessel of note moored in the area, aside from the U.S.S. Intrepid, a retired aircraft carrier and permanent floating museum, had been another, temporarily berthed, celebrated military ship. It was the Spanish Juan-Sebastián Elcano, also a tourist attraction. The third-largest tall ship in the world, and named for the captain who led Magellan’s circumnavigation of the globe, the 371-foot, four-masted topsail schooner was built the same year Charles Lindbergh completed the first solo crossing of the Atlantic, in 1927.

Interestingly, the Spanish Navy uses the relic as a globe-traveling “floating embassy” of sorts, celebrating Spain’s rich nautical history and serving as a living museum toured by schoolchildren and dignitaries, alike. With twenty-three officers, twenty-two NCO’s and 139 sailors aboard, the vessel doubles as a training billet for some Spanish midshipmen. In fact, during the ship’s 2014 visit to Manhattan from May 10-15, at least one school attended by children of folks involved in the Task Force’s criminal investigation had visited the iron-hulled behemoth. Surely, an innocuous side note. Until it wasn’t.

Spring became summer, and investigators were shocked to discover in July how far removed the two mystery men were from New York and the drug operation. Not only were they foreign nationals, they were Spanish Navy. Midshipmen at that, completing a six-month training cruise on the famous Elcano.

There was also a strong corroborating detail in the overall criminal investigatory fact packet: As part of an unrelated operation, agents from the Department of Homeland Security had nabbed two Colombian traffickers in New Jersey on May 13 of that same week in 2014. The men were caught with twenty-seven kilograms of cocaine, and camera footage revealed that the cocaine was delivered to the Colombians in Manhattan by three crew members from the Elcano. The like-themed July break in the Task Force investigation was like a fog lifting: If three guys had come ashore to deliver drugs in Manhattan (and later recovered in Jersey), it wasn’t hard to believe two others had been deployed to the Bronx. DHS, DEA, and TF members working the angles concluded that degree of criminal activity could implicate the Spanish Navy, or even the Spanish government.

Here’s where Torres’s background becomes so important. Back in the mid-1990s, as an undergraduate student at Georgetown, Torres spent a year studying abroad in Madrid, honing his pronunciation of the Iberian theta and immersing himself in the tendencies and idiosyncrasies of Spanish culture. Just a few years later, Torres capped off a Fulbright project in Bogotá, where he studied peace negotiations between the Colombian government and the country’s (now-demobilized) armed FARC insurgents, by accepting a position in-country as a program officer with USAID, the humanitarian arm of US foreign policy since the Kennedy Administration.

Put a pin in that for just a moment.

“We were initially shocked to learn that the Elcano had been used to traffic in significant amounts of cocaine and heroin [not just in the New Jersey arrests, but also in the Bronx case],” says Torres. “Then, it seemed to make sense: sophisticated drug smugglers and unscrupulous sailors capitalizing on the ship’s worldwide fame and easy access to ports in order to traffic drugs into some of the world’s most important markets, like New York City.”

It made sense. And it was clever. A sovereign naval ship is not ordinarily subject to US Customs checks, making the Elcano the ultimate contraband transport container. Crew members later told authorities that there were no controls checking them as they left or boarded the vessel, either. It was a perfect cover. Until it got blown, that is. And now, Colombia had emerged as a possible focal point—both in the New Jersey bust and the New York Special Narcotics Prosecutor’s case led by Torres.

“Looking back, we could have [closed the investigation] with the dealers in the Bronx and Connecticut and this still would have been a great case,” says Torres. “But the Elcano sailors opened the door to build a truly international case.”

In the end, it was a no-brainer for New York’s Office of the Special Narcotics Prosecutor to deploy Torres as the point man. And not just because he speaks Spanish. A generation ago at USAID, Torres took his job the same week the US showered Colombia with a $1.3 foreign aid program aimed at ending the drug-fueled insurgency in South America and the corresponding epidemic in the United States. Colombia, where criminal cartels rose out of the jungles in the 1970s to seize a major portion of the international cocaine market, was at the epicenter of the crisis. Torres was tasked with helping to implement the massive aid program in a country that was being torn apart, overseeing multimillion dollar programs to strengthen Colombia’s democratic institutions, provide humanitarian assistance to war victims, and create economic alternatives to coca cultivation.

“It was a crazy time to be in Colombia,” he recalls. “There were people around the world calling it a failed state. Assassinations, bombings, and kidnappings were rampant. It was one of the most violent places in the world.” Against that backdrop, Torres spent a half-decade soaking up intricate details about the conventions, characteristics, and realities of Colombian culture and government, and helped steer the society toward calmer waters. “Colombia today is a dramatically different country from what it was in the year 2000. The government’s partnership in bringing down drug trafficking is the result of years of trust and cooperation forged through effective diplomacy,” he says.

Fast-forwarding to Manhattan and the criminal investigation at hand, after three years of law school and a decade climbing the ladder as a New York City prosecutor, it was once again time for Torres to leverage every iota of that same savoir faire he’d cultivated in Colombia.

THE TIES THAT BIND

After the break in the investigation that implicated the Elcano that summer, the DEA and the Department of Homeland Security gathered evidence from the arrests made in New Jersey and from the takedown of the crew in the Bronx, and relayed it to Spanish authorities so they would be prepared when the Elcano arrived home in August from her deployment.

The Spanish Civil Guard quickly launched their own investigation. En route to its home port of Cádiz, Spain, the ship arrived in Pontevedra, Spain, on August 2, where Civil Guard and US Department of Homeland Security agents were waiting. Authorities detained three men—two sailors and a civilian assigned to the kitchen—implicated in the New Jersey bust, a case that had a two-month head start on the Bronx investigation in terms of establishing an Elcano link. A thorough search of the vessel in Pontevedra eventually turned up 127 kilos of cocaine stashed in a locker used to store spare sails, according to a Civil Guard statement. Spanish daily El País published accounts from sailors who said “everybody onboard knew the Elcano was smuggling drugs.” Meanwhile, Torres and Spanish authorities, conducting concurrent investigations on opposite sides of the Atlantic, worked to close the noose on the two midshipmen suspects from the Bronx case.

The tall ship, now sailing under a cloud of scandal that engrossed the entire country, port-hopped around Spain, as scheduled. When the Elcano reached the port of Cádiz in October, Spanish authorities finally had enough evidence to arrest the two midshipmen who had delivered the drugs in the Bronx. Torres flew to Spain, where he was escorted to a meeting room on a military base for a pre-dawn briefing with Civil Guard and military investigators. Authorities relayed the details they’d pieced together in Pontevedra and Cádiz.

According to the record, the Elcano had begun its six-month deployment back in mid-April of 2014. The voyage, which would include stops in France, Italy, Morocco, and the Dominican Republic, began by crossing the Atlantic and arriving in the Caribbean port of Cartagena, Colombia. Excited to walk on solid ground, her sailors streamed into Cartagena’s streets to take advantage of the beachside resorts and bustling nightclubs in the historic Spanish section of the city. Taxi drivers in the port, acting as recruiters for drug organizations, offered to connect sailors with traffickers for a chance at a massive payday. The two aspiring naval officers from the Bronx case had taken the bait, accepting an offer to deliver drugs to contacts in New York, then dutifully stashed cocaine and heroin in their underwear before returning to the ship.

Spanish authorities would convene military tribunals for the sailors, but Torres returned to New York with a case that now stretched not only to Spain, but all the way to Cartagena. Back in Manhattan, he immediately reached out to police in Colombia, who it turned out had been conducting their own investigation for more than three years into the trafficking group responsible for the drugs found aboard the Elcano, though officers had been unable to make an arrest. Partnering with Torres, Colombian investigators shared years of evidence, including hundreds of hours of wiretap recordings of the suppliers implicated in the Elcano scheme.

“We were able to get that evidence immediately because of the strong law enforcement partnership that exists between the United States and Colombia now,” says Torres. “That only happens when two countries are friends and have worked together for a long time. The legal field can be such a local thing, but when crime is globalized, you have to have lawyers who can function globally.”

To be sure, partnership is crucial, and Torres was precisely the right man for the job. In spite of his considerable capabilities and uncannily relevant work history, his contributions to building a case of such intricacy, one requiring extraordinary multinational transparency, is nothing short of remarkable. Amidst circumstances that could have been fraught with suspicion, jealousy, ego, intel-hoarding, and outright mistrust, Torres threaded a narrow needle eye to sew up critical collaboration and candor.

As officers entered into the suspects’ Connecticut destination, occupants inside furiously attempted to dump evidence down a sink. No sewer system could have handled the treasure trove.

INDICT, EXTRADITE, AIR TIGHT

Torres poured through hours of Colombian police wiretap recordings from May 2014, and when he reached the dates of the Elcanoport call in New York, there was a burst of activity. It was all there. Jorge Luis Hoayeck and Jorge Alberto Siado-Álvarez, the Colombian drug trafficking leaders who had hatched the Elcano scheme, were on the wire discussing every intricate detail of the events in the Bronx with their contacts in New York.

In May 2015, after the year-long investigation that called upon every shred of diplomatic, deal-making, and door-opening proficiency he’d acquired years earlier in Spain and Colombia, Torres was finally ready to bring a case to a grand jury in New York. Task Force investigators took the witness stand to recount the Bronx investigation, and the torrid forty-eight hours of activity in New York and Connecticut that followed the Elcano visit. Colombian police officers also testified to explain their case, ensuring that the wiretap evidence could be admitted in an American court. After a week of testimony, the grand jury handed down indictments against Hoayeck and Siado-Álvarez under New York’s kingpin statute, and Torres moved on to the next phase of the investigation: finding them in Colombia and extraditing them to New York.

First, the entire investigation had to be turned over to the Justice Department’s Office of International Affairs, where attorneys spent months reviewing every detail of the investigation, as well as American and Colombian criminal statutes and reams of bilateral international agreements. After more than six months of reviews and edits in Washington, and exchanges with counterparts in Colombia, the Justice Department approved the indictment and issued provisional arrest warrants for Hoayeck and Siado-Álvarez in January 2016.

“This elaborate scheme, spanning oceans, enabled high-end Colombian drugs to be smuggled aboard Spanish military ships, deep into the bowels of New York City. Today’s indictment brings this drug running route—and this alleged corruption in the Spanish military—to an end,” New York Police Commissioner William J. Bratton said at the time.

Colombian police officers quickly apprehended both men, who then spent months fighting their case in Bogotá until Colombia’s Supreme Court approved their extradition. Meanwhile, Torres and the Office of the Special Narcotics Prosecutor prepared for trial. Both extraditions were approved that fall, and DEA agents waited at a New York area airport in October 2016 as Hoayeck climbed down from a government plane in handcuffs. Siado-Álvarez followed in January 2017, and both men were housed in New York City jails, where Torres confronted them with the mountain of evidence police in the United States, Spain, and Colombia had gathered against them. It was obvious that a trial was a lost cause, and both men pleaded guilty at their first opportunity.

Siado-Álvarez was sentenced to eight years in prison. Hoayeck received seven years. Across the Atlantic, the two sailors with the backpacks from the stakeout in the Bronx pleaded guilty in tribunals and went to a military prison in Spain, while the sailors from the New Jersey case, having chosen to go to trial, continue to work their way through Spain’s military court system. Special Narcotics Prosecutor Bridget G. Brennan, Torres’s boss, applauded the teamwork, saying, “It was only through the collaboration of authorities in Spain, Colombia, and here in New York that we were able to disrupt this surprising smuggling operation.”

For Torres, that international collaboration was personal, and years in the making. He has effusive praise for the judges and police officers he worked with in Spain and Colombia, and he highlights the importance of understanding their cultures after living in both countries as a key factor in the successful prosecutions. Though he relentlessly deflects credit, Torres does concede the whole affair has a once-in-a-career feel to it.

“It’s one of those things that sort of fell into place,” he says. “It was such a cool case for exactly those reasons. It enabled me to combine every facet of my own experience, knowledge, and passion in a single investigation. I realize how rare that is.”

Writer Chad Konecky contributed to this story.