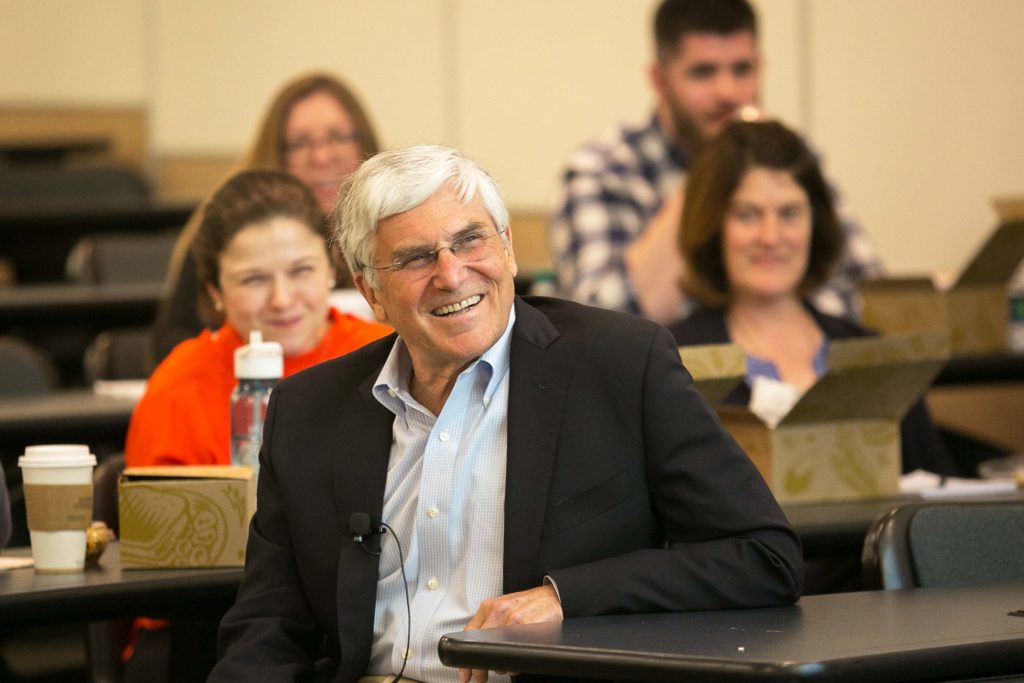

After a 41-year Army career that included the longest stint commanding Multi-National Force–Iraq of any coalition leader, General George W. Casey Jr. (Ret.) doesn’t have many unfulfilled career ambitions. Still, his address to a large audience on April 25, co-sponsored by BC Law’s Leaders Advancing and Entering Public Service (LEAPS) and the Student Veterans Association, gave Casey a chance to finally realize a desire to go to law school he’d harbored since his days at Boston College High School.

“My plan was always to go to law school after my two-year Army ROTC commitment was up,” Casey said. “Forty-one years later my wife said it was the longest two years of her life.”

Few would challenge the idea that Casey made the right choice. Throughout four decades in uniform, he rose to the rank of four-star general, leading troops in Bosnia during Operation Joint Endeavor, commanding a 30-nation coalition during the most difficult years of the Iraq War, and leading more than 1 million soldiers as chief of staff of the US Army. The experience left Casey uniquely qualified to give his lecture, “Civil-Military Relations: From the Constitution to the War on Terror.”

After a welcome from 3L and US Army Captain Curtis Cranston, Casey was introduced by Hon. Christopher Muse, a BC Law adjunct professor and Massachusetts Superior Court judge, who attended BC High and Georgetown University with Casey. “We comfortably rely on the rule of law,” Muse said, contrasting many countries where Casey was deployed to where “hate, violence, and chaos fill that void. Everyone in this room is motivated by a desire to promote a just society.” Muse chided Casey about his stalled legal career before stressing the importance of civil-military relations and ceding the floor to his boyhood friend.

Blending constitutional law, military history, experiences with senior administration and military officials, and self-effacing humor, Casey provided a dissertation on the importance of civil-military relations from the nation’s founding to modern conflicts in Iraq and Afghanistan.

“The relationship between a democratic society and its military is extremely important for the long-term health of the state,” he said, “but it needs to be cultivated. It’s not something we can take for granted.”

Casey used two case studies to illustrate the competing dynamics that regularly play out between civilian officials and military leaders: World War II and the first year of the Obama Administration as it grappled with troop levels and strategy in Afghanistan.

Casey highlighted successful interactions between President Franklin Roosevelt, his military commanders in Washington and the European theater, and allied leaders like Winston Churchill, to demonstrate how high-level civil-military relations is supposed to work. “General Marshall understood that in a democracy, presidents need victories,” he said, praising Marshall’s ability to keep military dissent private. “Politics is always a factor, but not the factor, in every decision to commit the military.”

Next, Casey shifted the discussion to the war in Afghanistan and the difficulties of managing civil-military relations in what he termed, The Media Age. Guiding the audience through the issues facing the early Obama Administration in Afghanistan, Casey described how the outsized media profiles of some military leaders, and several instances of public criticism of strategic and manning decisions, made an already difficult combat mission even tougher.

“It’s a lot harder to get things done today and have intelligent private discussions,” he said, adding that military dissent needs to happen but needs to remain private. “I’ve never been rebuked by a civilian leader for telling them what I thought. People only get in trouble when they do it in public before telling the President.”

Casey took audience questions on topics ranging from the Vietnam War to Defense Secretary James Mattis’ resignation before returning to the importance of his main topic. He stressed that civil-military relations needs to be cultivated in both directions. “It’s deeper than just, ‘Thanks for Your Service,’” he said.