Ever since their publication in 1840, four years after their author’s death, James Madison’s notes on the Constitutional Convention have been treated by historians and constitutional lawyers as if they were impartial and uniformly accurate. Madison’s Hand, a new book by Professor Mary Bilder, will likely give the historians and lawyers pause. Bilder’s painstaking analysis reveals for the first time the extent to which Madison revised the notes during the time between the 1787 Convention and his death, in 1836. It also reveals the self-serving nature of some of the revisions. Madison tried to reshape perceptions around his own position on slavery, for example. In the words of Michael W. McConnell, director of the Constitutional Law Center at Stanford Law School, “Anyone who wants to understand the Constitution must take this book into account.” Or as Bilder herself says, “Everyone—historians, political scientists, lawyers, judges—has used the revised text as if it were written in the summer of 1787, and the book makes it very difficult to do that from now on.”

Q. What new insights does your book provide about the Convention and Madison’s role there?

A. I want people to realize that even at the Convention’s end, the Framers didn’t see the Constitution the way we see it. In 1787 things were moving very fast, and the delegates were struggling to stabilize the country. Madison wrote his notes that summer twice a week—and he was already revising his understanding of what had happened.

The notes started as a political diary, charting Madison’s hopes and frustrations. He wanted proportional representation in both houses—and he failed. He wanted a national government that could veto state laws—and he failed. By late July, he was pretty much on the outs of the Convention. But his notes turned out to be really helpful in rewriting drafts of the Constitution. By the end of the Convention, he’d reasserted himself as one of the most important members.

Q. Why did Madison revise his notes? For clarity and accuracy? To provide greater detail? To reflect new concerns, new political expediencies, changing views, or new understandings of the Convention or the Constitution? To put a shine on his own politics or public image?

A. All of the above. In his revisions to the notes, he integrated procedural and textual details from his secret copy of the official Convention journal. These revisions made Madison and the Convention seem particularly focused on text and procedure. He also moderated many comments, to give himself a more precise and measured tone, and he took others’ broad comments and narrowed them. And, having joined Jefferson’s Republican Party, he replaced his own speeches, which contained ideas opposed to the Republican agenda, with revised speeches in which those ideas were absent. He also now described the new government as a “Republican Government.”

He was surprisingly fussy about language, too. If he had used a word twice, he changed one of them to a synonym.

Q. Name Madison’s most significant revision.

A. The first sentence of the original notes read: “Monday May 14 was the day fixed for the meeting of the deputies in Convention for revising the federal Constitution.” In May 1787, the sentence made sense. Madison disliked the “federal” structure of the old government, in which the states were equally represented. He wanted a “national” government. And the government under the Articles of Confederation was a federal Constitution.

But years after the Convention, meanings had changed. The 1787 Constitution was now the federal Constitution, with “federal” referring to the mixed structure of representation in Congress. So Madison deleted “Constitution” and inserted “system of Government.” The sentence now meant that the Framers had transformed American history.

Q. Are there parts of the notes where historians should tread with particular care?

A. They should take special care with the section from August 22 to September 17; it was composed from rough notes filled with likely indecipherable abbreviations, and much of it is simply a copy of the official journal. We should also be careful about some of Madison’s most famous speeches—a number are on sheets that Madison substituted for his original ones.

Q. Madison opted for posthumous publication of the notes. Why?

A. He was the last Framer to die, in 1836, but other Framers lived into the late 1820s, and some had also kept notes. I think Madison worried that if he published his notes, others would say they misrepresented his positions in Philadelphia, which favored strict limits on the states’ power and giving the executive considerable authority.

Q. How should your findings influence “original intent” jurisprudence?

A. As I write in my conclusion, “If original understandings of the Convention existed, we cannot retrieve them. Indeed, hours after the Convention ended for the day, Madison could no longer recover it precisely for himself.”

The Constitution was contested from the beginning.

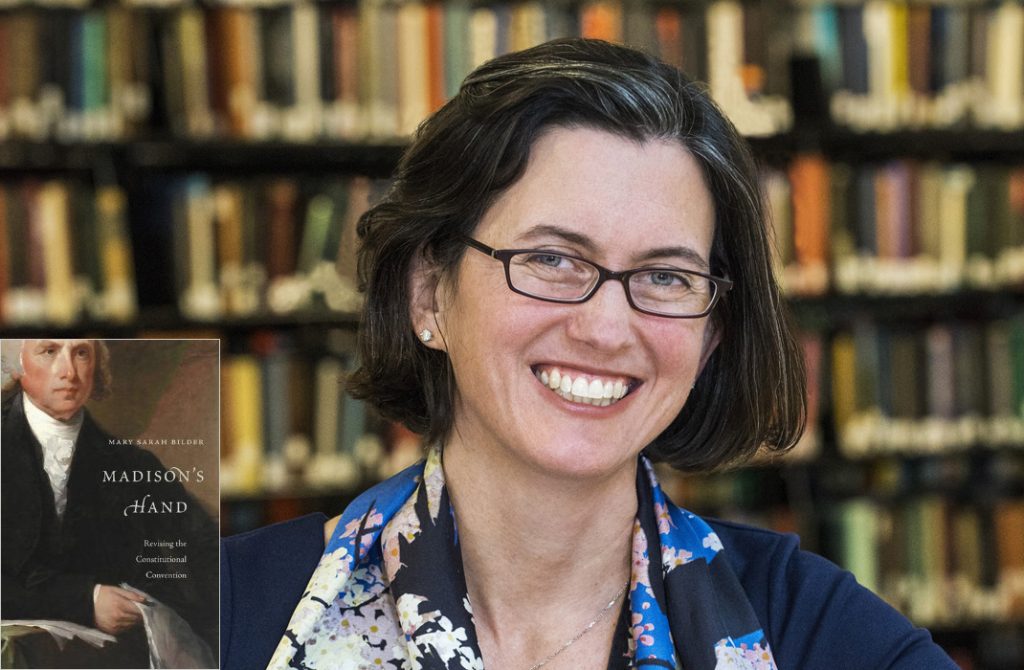

Mary Sarah Bilder is Professor of Law and the Lee Distinguished Scholar at Boston College Law School, and author of Madison’s Hand: Revising the Constitutional Convention (Harvard University Press, 2015). Richard Beeman, author of Our Lives, Our Fortunes and Our Sacred Honor, called it “an exceptionally important piece of work that will have a profound impact on all future work on the Constitutional Convention.” She is the author of The Transatlantic Constitution: Colonial Legal Culture and the Empire (Harvard University Press, 2004), awarded the Littleton-Griswold Award from the American Historical Association. Her articles appear in several important collected volumes of essays and a wide variety of journals, including the Yale Law Journal, the Stanford Law Review, the Yale Journal of Law and the Humanities, the George Washington Law Review, Law and History Review, Law Library Journal, and the Journal of Policy History. She co-edited Blackstone in America: Selected Essays of Kathryn Preyer (Cambridge University Press, 2009).