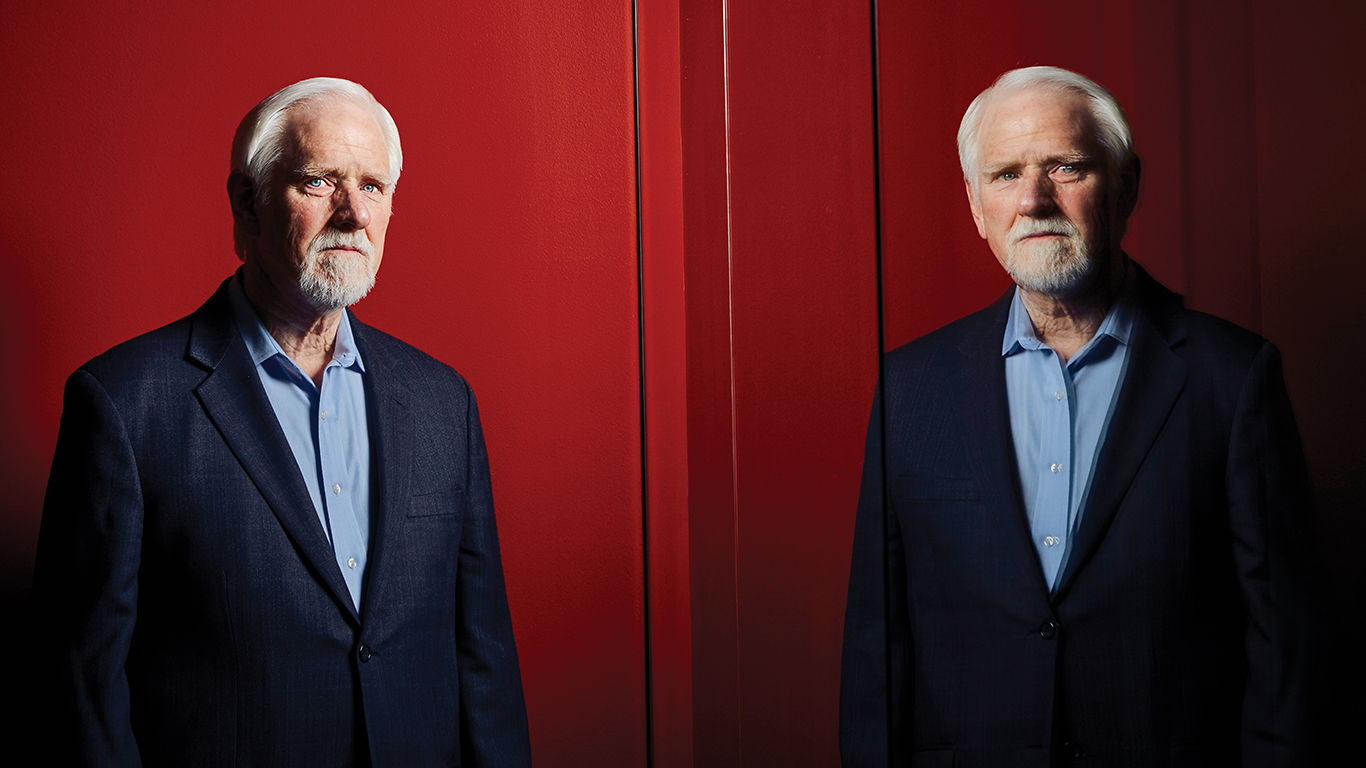

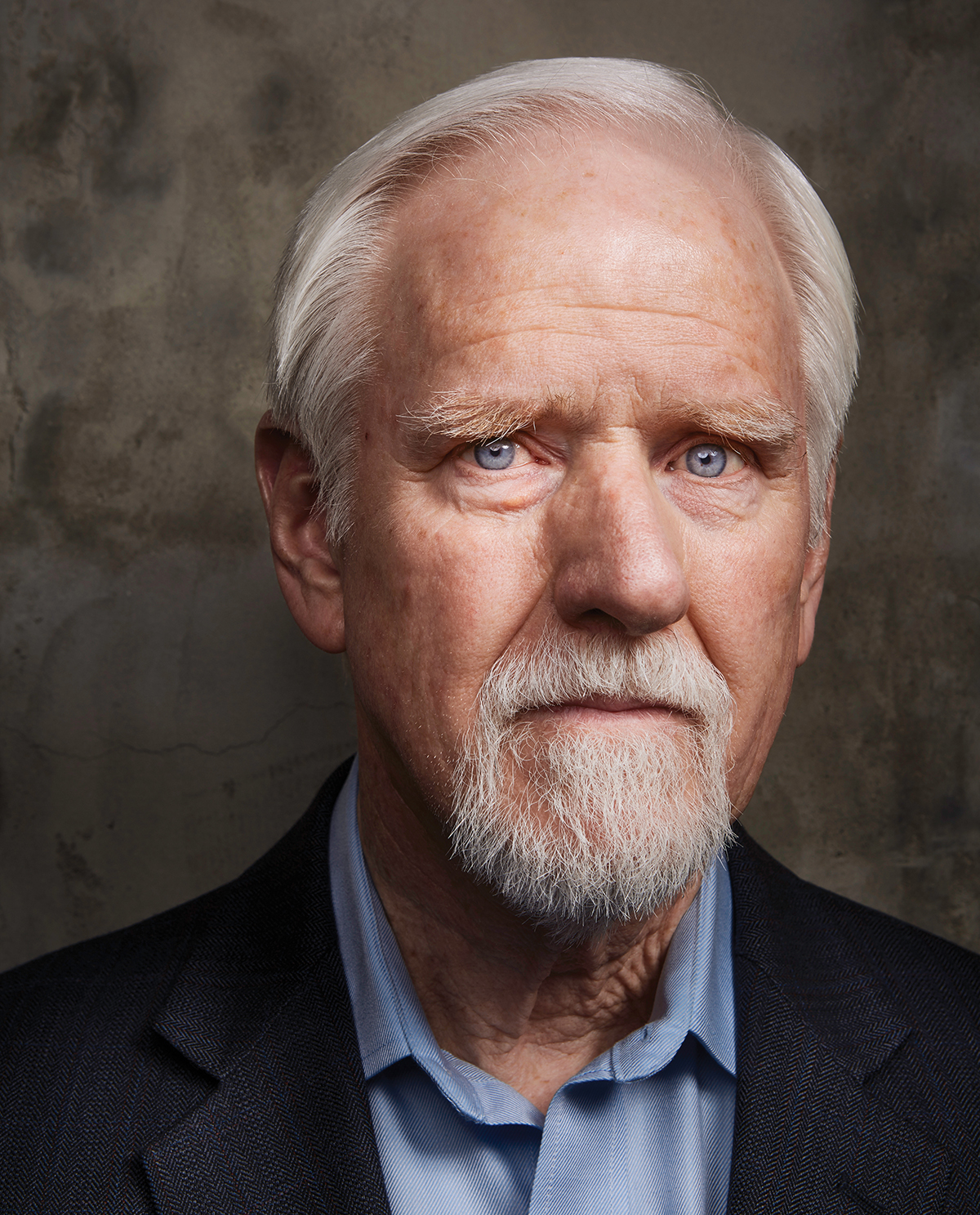

Walt Kelly ’68 didn’t have a starring role in Making a Murderer. He wasn’t a player in the sexual assault case that sent Steven Avery—an innocent man—to prison for nearly two decades. Nor was he involved in that same defendant’s subsequent murder trial and conviction following his exoneration from the assault verdict.

Rather, Kelly’s part in the saga that spawned the documentary Forbes magazine dubbed “Netflix’s most significant ever,” was about making amends. Kelly represented Avery in a civil suit during a short-lived but symbolic oasis of legal and ethical recompense sandwiched between two bitterly contested criminal cases.

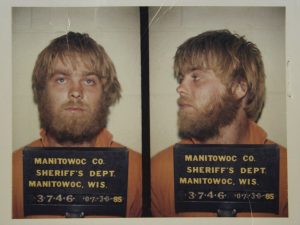

The streaming documentary Making a Murderer chronicles the story of Steven Avery, who had a relatively low-key criminal record and lived on the lot of his family’s auto salvage yard in rural Wisconsin. Convicted of first-degree sexual assault in Manitowoc County in 1985, Avery spent eighteen years behind bars before being exonerated by DNA evidence in 2003.

Enter Walt Kelly, well known in civil liberties circles, who would become half of the two-man team that Avery chose to represent him in a $36 million wrongful conviction civil action.

The lawsuit was filed in 2004 and within a year, the plaintiff’s legal team had Manitowoc County against the ropes. Case files and depositions clearly demonstrated gross misconduct by the former district attorney and retired sheriff in their push to secure Avery’s 1985 conviction.

In 2005, with his lawsuit poised to commence, Avery was arrested for the murder of a photographer who was last seen on his property. His wrongful conviction case fell apart. The documentary indicates that a vindictive and dishonest police department may have framed Avery because of the pending lawsuit.

Kelly’s trajectory to accompanying Avery to the doorstep of a likely civil victory in 2005 was seemingly random. But in many ways, Walt Kelly was predestined to end up as Steven Avery’s lawyer.

Kelly was well into his fourth decade as an attorney when he took Avery’s case. He was eminently qualified, except for one rather conspicuous fact. He had never represented a wrongfully imprisoned criminal defendant before. In this particular forum, he was—and remains—a rookie. “Steven’s [post-]exoneration case is the first and last exoneration case I’ve done,” Kelly confirms, sounding as if he himself is still somewhat surprised by the detail.

Be that as it may, by the time he accepted Avery as a client, Kelly was deeply familiar with ACLU and civil rights issues. He also knew staff at the Wisconsin Innocence Project, which had secured the DNA testing that proved Avery’s innocence in the sexual assault case. Kelly had previously won a well-publicized police and DA misconduct lawsuit just a ninety-minute drive from the county line in Manitowoc.

Joe Goldberg, a former BC classmate, insists that Kelly’s status as a wrongful-conviction neophyte wouldn’t have sent him, Goldberg, in search of alternative counsel had he been in Avery’s shoes.

“Walter exemplifies what you really want in a lawyer,” says Goldberg ’68, a senior shareholder at Freedman Boyd in Albuquerque, New Mexico, and one of the most respected plaintiffs’ antitrust litigators in the country. “He’s smart, aggressive, and persistent. That’s what Walter was as a law student, and it’s what he’s shown himself to be as an attorney. If you were in trouble, you would want Walter as your lawyer.”

Avery’s 1985 conviction was vacated via unequivocal DNA evidence in September of 2003. By then, Gregory Allen, the actual perpetrator of the assault on the woman named Penny Ann Beernsten, was already serving a sixty-year sentence for his conviction in a 1995 sexual assault.

Before taking on Avery’s civil lawsuit, Kelly enlisted some help. He didn’t have an active criminal practice at the time, and that made him uncomfortable. He called Steve Glynn, a friend and Milwaukee-based criminal defense attorney with a long record of representing clients he believed to be falsely accused of crimes. Unbeknownst to Kelly, Glynn had represented Avery almost ten years earlier in the first of two post-conviction attempts to use DNA evidence to prove his innocence.

With the legal team in place, the objective was clear.

“We knew the case was going to involve constitutional violations of the exculpatory laws under Brady v Maryland, says Kelly. “We had to prove that the sheriff and the DA, acting for Manitowoc County, had violated Steven’s constitutional rights in securing his arrest and conviction in the sexual assault case.”

As Kelly notes, the core of the lawsuit would be built upon section 1983 of the US Code, which applies to deprivation of rights secured by the Constitution. Job No. 1 in crafting the suit was pouring through a mountain of documentation. The existing record was enormous and everything had to be reviewed: the entire criminal proceeding from 1985 in addition to the post-conviction efforts to secure Avery’s release prior to his exoneration, as well as records compiled by the Innocence Project.

“Our depositions brought out the very aggravated nature of the constitutional violations. In fact, some of their conduct was so egregious that there was the possibility of a federal criminal civil rights investigation. That was the start of affairs.” —Walt Kelly

Kelly and Glynn decided to withhold filing a suit for damages until the completion of an ongoing investigation into Manitowoc’s handling of the Avery case by the Wisconsin Attorney General.

“Our thinking was that the AG would be very likely to find misconduct, which would help the civil suit,” explains Kelly. “We also wanted the DOJ investigators to ‘have at’ all of those witnesses in order to put meat on the bones of the story that we could then use in the civil suit. It turned out that we had a great disappointment with the AG’s ultimate conclusions.”

Former Attorney General Peggy Lautenschlager’s fourteen-page findings concluded there was “no basis to bring criminal charges or assert ethics violations against anyone involved in the investigation and prosecution of [Avery].” The document was released in December of ’03, just weeks after Avery was set free.

The surprising outcome was a blessing in disguise. As part of the discovery for Avery’s lawsuit, Kelly and Glynn got access to all the investigatory reports that formed the basis of Lautenschlager’s decision.

“In truth, what happened in that case was that inside the Wisconsin DOJ, Lautenschlager’s investigators were very strongly in favor of finding misconduct,” says Kelly. “But it was the AG and one of her deputies who made the decision not to do that. And we had all of those internal documents.”

Before Avery’s legal team had deposed a single witness, there was an arsenal of ammunition from the AG’s office supporting a section 1983 claim. Meanwhile, Avery’s story had entered the national consciousness and Avery himself had become a statewide symbol of a broken criminal justice system in need of repair.

Ultimately, Kelly and Glynn deposed almost forty witnesses on Avery’s behalf. Each set of testimony was more damning than the last and supported the allegation that Avery had been the victim of aggravated constitutional violations. Legally speaking, it was a bloodbath.

“I think the depiction of the Steven Avery story in the [Netflix] series is a positive good,” says Kelly. “It reveals the underbelly of the criminal justice system. Although this is a spectacular case in itself, these operations and biases and countervailing forces that go on in the criminal justice system are daily events. And they require us to think twice about what’s important in that system.”

As the discovery period progressed in Avery’s civil suit, two moments in particular sent a charge through his attorneys.

First, they elicited testimony revealing that Manitowoc County detectives had begun round-the-clock surveillance of Gregory Allen two weeks before the sexual assault on Beernsten in 1985. However, surveillance of Allen was temporarily suspended on the day of the assault because police resources were redirected to another case.

What’s more, Beernsten continued to receive threatening phone calls after Avery’s arrest, which county sheriff Tom Kocourek dismissed as immaterial. Worst of all, just days after Avery’s arrest, a Manitowoc County detective informed Kocourek that Allen was not under surveillance when the attack occurred, and it was likely that the wrong man was in custody. The detective was told to steer clear of matters outside his jurisdiction.

A second high point during discovery was equally incriminating. Beernsten had identified Avery as her assailant using an image array of suspects. But deposition testimony confirmed that the sheriff’s department had used a booking photo of Avery to generate its forensic composite drawing.

The misstep? The mug shot that inspired the drawing was taken in January of 1985, and Avery’s appearance at that time was dramatically different from how he looked when he was arrested in July. Meanwhile, the department possessed and was aware of a 1983 booking photo of Allen that looked a lot like Avery’s composite drawing, but omitted it from the image array Beernsten reviewed.

“Those were the two moments when we knew—to a degree that you rarely know in a civil right’s suit—that we had the defendants, ice-cold,” recalls Kelly. “I will tell you that in my mind and [co-counsel] Steve Glynn’s mind, if we had to go to trial, the only issue was going to be: ‘how much?’

When Kelly and Glynn filed Avery’s lawsuit on October 24, 2004, the dollar demand wasn’t arbitrary. Using a survey by the Innocence Project of wrongful conviction exoneration awards, along with other recent data from across the country at the time, Avery’s lawyers did their best to extrapolate. The grand total: $18 million in compensatory damages for targeting, personal hostility, and obstruction of justice, along with punitive damages of an additional $18 million.

The math involved a little alchemy (and helped to set precedent) since these were the early days of DNA exoneration cases and associated lawsuits. Kelly explains how the team arrived at $36 million.

“We looked at the eighteen years served (of a thirty-two-year term) and we looked at the incredible losses that Steven had taken. Not only the possible loss of his mind, but the loss of his marriage and the loss of contact with his children. We thought that a million dollars a year was reasonable based upon everything we knew. Then, we looked at the developing law of punitive damages, and one of the [key components] was and is some kind of a reasonable ratio between the punitive damages demand and the compensatory damages demand. We decided to make that ratio one-to-one.”

At this point, the case was essentially all but over. Except for the payout.

“Everybody knew [we were going to win],” says Kelly. “The defense lawyers knew as well. Our depositions brought out the very aggravated nature of the constitutional violations. In fact, some of their conduct was so egregious that there was the possibility of a federal criminal civil rights investigation. That was the state of affairs.”

Attorneys Kelly and Glynn deposed witnesses on Steven Avery’s behalf. Each set of testimony was more damning than the last and supported the allegation that Avery had been the victim of aggravated constitutional violations. Legally speaking, it was a bloodbath.

The goings-on behind the scenes in Manitowoc County at the time affirmed Kelly’s optimism. Throughout the pretrial phase, the county looked at every insurer it had a relationship with and which among them might qualify as a potential indemnifier, then made a tender of defense to each of them.

According to Kelly, Manitowoc was telling its insurers: “We think you’re covering us on this; we want you to represent us and indemnify if there’s a judgment.” Without exception, the insurers replied with a reservation of rights letter. In the simplest terms, they were cautioning the county: “We’ll represent you, but if Steven Avery and his lawyers are able to prove what they say they are going to prove, we’re not going to cover you.”

“It was dramatic,” recalls Kelly.

Avery’s lawyers completed a particularly revealing deposition supporting their claim in late October of 2005. A few days later, on Halloween, Wisconsin photographer Teresa Halbach disappeared. Her last known destination was the Avery salvage yard to photograph a vehicle for Auto Trader magazine.

A swift investigation followed, featuring striking discoveries and bizarre investigative phenomena (this is the part where you have to watch the show). Avery was arrested in November and pretrial testimony produced enough evidence for him to be held for trial.

Predictably, Avery’s civil case unraveled.

“Once the investigation commenced, I would say it didn’t take long at all for Steven to fall from a state of grace to a state of ignominy because of the accusation that he had mutilated and murdered Teresa Halbach,” says Kelly. “Steve Glynn and I went through the transition where we handed off all that we had from the civil suit to Dean Strang and Jerry Buding, who were the lawyers we recommended to Steven and his family for the [new] criminal case.”

In December of 2005, Avery accepted a settlement with Manitowoc County for $400,000. He needed the money to foot the bill for his new criminal defense team. The county accepted no fault or liability regarding Avery’s 1985 wrongful conviction in the deal. All told, Avery received just over $22,000 in annual compensation after serving eighteen years for a crime he didn’t commit. On June 1, 2007, Avery was sentenced to life in prison for the murder of Halbach.

Kelly prefers not to call the outcome of the civil suit a legal loss. “We all had a specific legal goal and approach, and it was achieved. Only afterwards were the exigent circumstances such that we had to settle for what we could get.”

And what of Steven Avery’s fate?

“I’ll tell you, I don’t think it’s over,” Kelly says. “He’s retained new counsel to continue to challenge his conviction. This is an ongoing story as far as I’m concerned.”

In a broader sense, the sudden turn of events in Avery’s lawsuit can’t diminish the worth of cases Kelly has made a habit of taking on.

“Lawyers like Walt Kelly have spent much of their careers beating their heads against the wall,” says BC Law Criminal Procedure Professor Robert Bloom ’71, a former civil rights attorney and co-author (along with Professor Mark Brodin) of Criminal Procedure: The Constitution and the Police. “Sometimes, those are immovable walls. That doesn’t stop these folks from continuing to go ahead and do these things. Walt Kelly is a hero to me. And a hero to some of my colleagues too.”

Kelly is a Newton native, the son of a litigator who transitioned to business and became CEO of a General Electric subsidiary. Kelly’s dad was from “that generation of Irishmen who cracked the barrier at Harvard College and Harvard Law School.” Predictably, the law was a regular topic of conversation around the dinner table.

As a consequence, Kelly arrived at BC with a deep-seated respect for the law. But those influences could not have shaped the course of Kelly’s career if not for a certain confluence of events.

First, Robert Drinan, SJ, was dean of the law school when Kelly was a student. A Catholic priest, Father Drinan was a member of the Massachusetts Bar, owned a doctorate in theology, and was later elected to the US House of Representatives. He was educated and iconoclastic. A colossal role model.

The cultural milieu of that time was equally compelling. Kelly entered law school two years after President Kennedy’s assassination and the same year Lyndon Johnson sent the first American combat troops to Vietnam. Weeks before Kelly graduated, Martin Luther King Jr. was killed, and shortly afterward, Robert Kennedy met a similar fate. Meanwhile, Kelly’s tenure at BC also coincided with the Warren Court’s transformation of the American legal landscape.

“Bob Drinan was a remarkable man and certainly had a lot to do with setting me on course for the career I’ve had,” says Kelly. “There was a sense in the air when we were all there from ’65 to ’68 that human rights and civil rights get a priority. A sense that, as much as lawyers are devoted in so many fields of their work, doing this work is particularly important. The school set that tradition and it still does.”

The BC Law environment and the churning societal mores of the day represented an external “pull,” but Kelly’s built-in desire to battle on the right side of history constituted the “push.”

“He’s just an incredibly passionate person, and you could see it from day one in law school,” says Cary Coen ’68, a classmate of Kelly’s and a retired attorney. “Every day, he was totally engaged in all the issues that come up in those classes and in debating them. I didn’t know him before law school, so it was incredibly noticeable. I think perhaps what’s unique is, Walt’s love for the law continues almost fifty years later.”

Kelly scored a clerkship with the late US District Court Judge Raymond Pettine in Rhode Island. A Johnson appointee, Pettine once said the Constitution should be interpreted in ways that “give meaning to the heart and soul of what it’s all about: a kinder, more understanding Constitution that recognizes the disenfranchised, the poor, and underprivileged.” For Kelly, it was a match made in heaven.

When his two-year stint with Pettine ended, Kelly took a job as a trial attorney and spent a year in the private sector before joining the administration of newly elected Wisconsin governor Patrick Lucey. Kelly served as Executive Director of the Wisconsin Council on Criminal Justice under the governor, a state and federal revenue-sharing program for improving the criminal justice system.

Lucey, who died in 2014, was a hard-nosed progressive who once summed up the essence of his political success by quoting a volunteer: “The big shots are against you and the little shots are for you. But there are a lot more little shots than there are big shots.” Clearly, during Kelly’s two years in the state capitol, another critical building block of his professional raison d’être slid into place.

He began practicing law again in Milwaukee in 1973, ultimately becoming a partner in a labor and employment trial and appellate practice, where he spent seven years before becoming a partner in his own practice, Sutton & Kelly. In 1994, he opened the solo practice that he maintains to this day. His current Milwaukee-based firm focuses on general trial and appellate work, emphasizing employment and labor law, trade regulation, civil rights, and discrimination.

By the time Avery hired him, Kelly owned considerable civil liberties bona fides, having spent more than a half-decade in consecutive terms as Chairperson of the Board of Directors of the Wisconsin American Civil Liberties Union, and as the Wisconsin Representative to the ACLU’s national Board of Directors.

“My early and continued trial and appellate work in labor was an invaluable experience,” says Kelly. “It definitely informed my approach to civil rights, and it informed my approach to the Avery case.” The release of Making a Murderer this past December thrust Kelly’s representation of Avery and the criminal proceedings that followed into the national dialogue. Soon, Professor Bloom was inviting Kelly to BC Law to discuss the case and Kelly brought along Avery’s criminal defense attorney Dean Strang.

“I think Walt is an excellent example of what we call a reflective practitioner,” says BC Innocence Program Director Sharon Beckman, who is also co-director of the Boston College Criminal Justice Clinic and planned the Kelly/Strang visit with Professor R. Michael Cassidy, faculty director of the Rappaport Center for Law & Public Policy.

“All of us on the faculty are really hoping to empower our students to think first about what kind of career would give them joy,” Beckman explains. “Something they would be good at and something the world needs them to do. Walt did a better job teaching that to our students than perhaps we could do because he’s such a living example of that.”

Indeed, Kelly used the end of the panel discussion at BC Law as just such a teaching moment. Acknowledging that there is still ambiguity about Avery’s murder conviction, he said: “Here’s an ethical provocation. Should Steven Avery’s life sentence be reduced by the time served for the crime he didn’t commit?”

Chad Konecky is a regular contributor to BC Law Magazine. His most recent article was “No Biz Like Showbiz,” about Netflix senior counsel Joel A. Goldberg ’92.