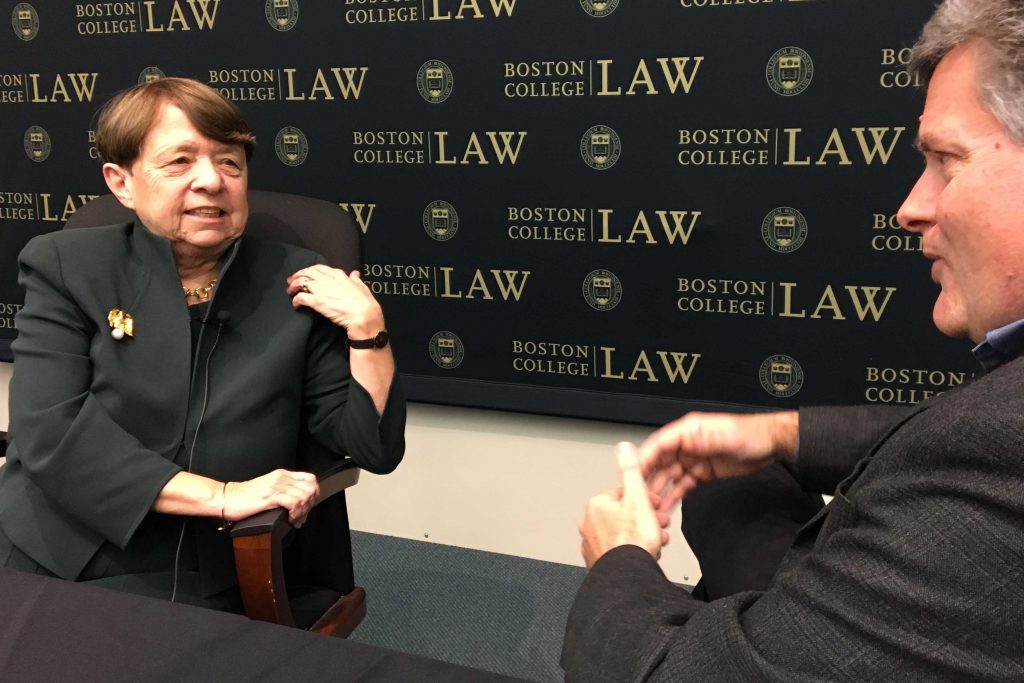

Very often, law students are encouraged to concentrate in one field of law. Specialization is a cornerstone of efficiency, but careers have the potential to take many different directions and we must not overlook an opportunity even if we feel out of our depth. Such was one of the many lessons conveyed to students by Mary Jo White, former US attorney for the Southern District of New York and former chair of the SEC, during a visit to BC Law in February.

White admitted that she was somewhat of an “accidental law student” even though the men in her family—her father, uncles, and brother—were all lawyers. When considering graduate school, she kept her options open, applying to programs in both psychology and law.

Though she began on the psychology track, White switched to law school, which, she said, “I found far more interesting than what I was doing.” Throughout law school and her early career in firms, she gravitated toward litigation: “I liked the combat…of taking other people’s problems and dealing with them.” She later left private practice to become acting US attorney for the Eastern District of New York, where the trial of mob boss John Gotti dominated her tenure.

White was named US Attorney for the Southern District of New York as the city was dealing with the first World Trade Center bombing. “In the aftermath, our office was the first out of any federal DA to form a counter-terrorism task force,” she said. “In my small way, I tried to blaze a trail of cooperation between the FBI and the DA’s office.”

When White was chair of the SEC—having been nominated for the post by President Obama in 2013—she strove to be an independent enforcer of federal regulations. “You don’t refuse the President,” she said, “but as a federal officer, I really tried to oversee regulations without political interference.”

Professor Brian Quinn moderated the conversation with White, who is now senior chair at Debevoise & Plimpton.

Story above by James Barasch ’18. Photo by Vicki Sanders

An Ethics Stress Test

Most people would agree that filling out bureaucratic forms is an annoyance; few may realize that when it comes to government ethics, not following instructions accurately and completely can threaten the system that guards against conflicts of interest throughout government, from the President’s office on down. The set of norms that govern conflicts have become fragile, said Robert Rizzi, an authority on the topic who spoke at BC Law’s Rappaport Center for Law and Public Policy. The title of his speech was “Conflicts of Interest in the Era of Trump.” Government ethics are now “undergoing a stress test,” he noted, which is challenging norms and assumptions and exposing design flaws in the structures built to support the Emoluments Clause of the US Constitution, the Office of Government Ethics (OGE), and beyond. Rizzi teaches a course on government ethics at Harvard and is a partner at Steptoe & Johnson, representing political appointees requiring Senate confirmation.

Legal Historian Studies Gay Nightlife

BC Law’s Legal History Roundtable in February hosted a presentation by Harvard Professor Anna Lvovsky titled “Laws, Gay Bars, and the Politics of Common Sense.” Here is a synopsis of what she discussed: Queer nightlife in the early twentieth century thrived in a period of minimal scrutiny by municipal authorities. With the end of Prohibition in 1933, all that would begin to change, as newly established liquor boards worked alongside local police departments to enforce a host of regulations against serving gay customers in licensed bars. The vast terrain of anti-homosexual proceedings provides a rich window into queer life in the mid-twentieth century: a record of the many bonds of friendship, unusual commercial alliances, and acts of resistance that defined the gay social world in these years. But that history is also notable for what it reveals about the dynamics of anti-homosexual regulation itself, and specifically how that project intersected with the broader public discourse about homosexuality in the mid-twentieth century…. In context, the ongoing litigation surrounding the boards’ anti-homosexual proceedings went far beyond a legal dispute about the liberties of gay men and women in the public sphere. It was also a cultural debate about the nation’s prevailing understandings of deviant behavior.

Fuzzy Logic

A chemist with a long history as an expert witness talked “Chemistry, Fuzzy Logic, and the Law” at BC Law on February 13. In his presentation to the Property and Technology Forum, Joel Bernstein said that though chemistry is thought of as an exact science, in reality it is not based on absolutes but rather on general rules and exceptions to those rules. This sets up a “fuzzy logic” in their work that cannot always directly translate to the law’s binary approach to questions about patent validity and infringement. He went on to explain to students how to work with expert witnesses of all types. Bernstein has written on the topic in the Israel Journal of Chemistry. His talk was hosted by the Program on Innovation and Entrepreneurship.

Alumni on Campus

Two alumni, Susan Beaumont ’86 and Nicholas O’Donnell ’03, also made appearances at BC Law in February, Beaumont to talk about her work as vice-president of law and real estate for TJX Companies, and O’Donnell, a Sullivan and Worcester attorney specializing in art law, to discuss recovering stolen art.

Respecting One Another

A diverse group of BC Law’s student organizations presented “Culture Shock: Microaggressions and the Road Towards Progression” in February to enable a transparent discussion of experiences of students of color at BC Law. The goal was to develop a deeper understanding of students’ identities, needs, and desires and to foster a stronger sense of community and cross-cultural awareness and respect.