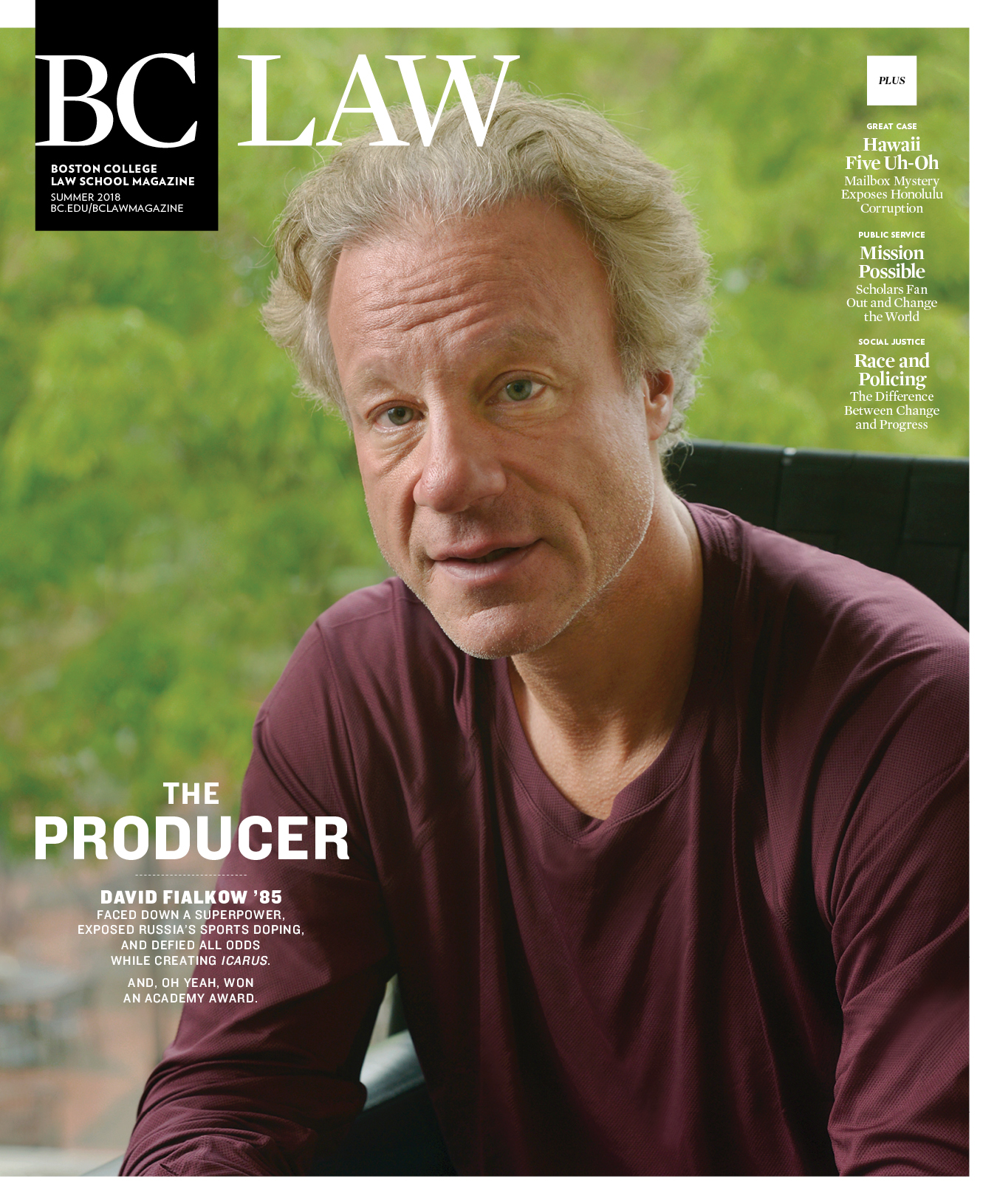

Little gets in Vladimir Putin’s way, and almost nothing that does stays there. To raise his ire or imperil him is to risk everything. David Fialkow ’85 is an exception to this rule. In 2018, a film project he produced unmasked Putin and the Russian Federation’s perversion of international sports and crippled Russia’s athletic prowess at this February’s Olympic Games.

Fialkow co-produced the Oscar-winning documentary film Icarus, a project the Russian government despised long before it debuted at the Sundance Film Festival in January 2017. In the course of being made, the movie project stumbled upon a massive performance-enhancement cheating scandal inside one of the world’s largest and most respected anti-doping laboratories, in Moscow.

Evidence gathered during the shooting of Icarus, which began as a story about performance-enhancing drugs (PEDs) and world class cycling, directly led to the banishment of Russian track and field athletes from the 2016 Rio Summer Olympic Games, and eventually brought about the barring of all Russian athletes from competing under their own flag at the 2018 Winter Games in Pyeongchang, South Korea. Documents secured by team Icarus remain the world’s only hard proof of cheating by Russia’s Ministry of Sport.

The Boston Globe nearly underbilled the magnitude of the moment earlier this year when it proclaimed that the movie sparked “an international incident with Russia, one with seismic, still unfolding repercussions.” Consequently, Putin probably knows more about David Fialkow’s life and times and comings and goings than anyone close to Fialkow should be comfortable with. What the former KGB chief may not realize is that he got beat on the global stage by a guy who used to sell Fuller brushes to make ends meet. You don’t have to be a fan of Tolstoy to appreciate that level of poetic justice.

Now that he’s part of an Oscar-winning team, it smacks of faint praise to characterize Fialkow as a filmmaker “on the side.” Be that as it may, he’s only produced documentary films as a hobby for the past decade. His day job is as co-founder and managing partner of the Cambridge-based venture capital firm, General Catalyst. Fialkow isn’t even the longest-running movie producer in his own house; his wife, Nina (née Sing), has worked as an independent producer, mostly for PBS, since the 1980s.

The Newton native’s particular interest in the Icarusplotline was distinctly personal. He is a passionate sports fan and a heavy-duty cycling enthusiast. One call of duty among his many philanthropic endeavors is serving as chairman of the Pan-Mass Challenge, a 100-plus mile bike-a-thon and fundraising titan for the Dana-Farber Cancer Institute. “David loves biking, loves sports and he has a huge level of integrity,” says childhood friend, business partner, and fellow alumnus Joel Cutler ’84 in answer to how the match was made between the film financier and Icarus director Bryan Fogel. “The idea of cheating in sports is just repugnant to him. The idea of cheating at all is repugnant to David.”

Cutler’s is a useful rough sketch. Yet Fialkow’s success as a documentary film producer, including the current highpoint with Icarus, has considerably more to do with his gift for putting people together at the right time and place, along with his vigor for seizing opportunities.

Fialkow has always had a highly developed sense of industry. He earned his diploma at Buckingham Browne & Nichols School in Cambridge in 1977 and attended Colgate University, where he was courted as an athlete (racquetball), before graduating in 1981. He deferred his acceptance to law school for a year to travel and continue overseeing a successful T-shirt business he’d started. The son of retired Boston attorney Jay Fialkow, he was rarely idle. Between high school and his time at Boston College Law School, Fialkow pounded the pavement as that aforementioned Fuller Brush salesman, tended bar at Cityside on Beacon Street, and even washed UPS trucks in order to support himself.

The job he calls “transformational,” however, was when he was a driver for Thomas H. Lee, a pioneer in the treacherous alchemy of leveraged buyouts. Lee’s firm, founded in 1974, is among the oldest and largest private equity firms in the world.

“I just drove the car, but Tom was a brilliant business tycoon who taught me a lot about the business world,” says Fialkow, who was attending BC Law at the time. “He was the one who impressed upon me that ‘it’s not what you do, but who you do it with, or for.’”

Enter Bryan Fogel. An avid cyclist from the age of thirteen, the Colorado native was both disillusioned and captivated by seven-time Tour de France champion Lance Armstrong’s 2013 admission that he had used PEDs. Fogel struggled to comprehend how his onetime idol and self-described “most tested athlete on planet earth” had kept his secret hidden over twelve years and throughout nearly 300 blood tests.

Theorizing that the system designed to catch cheaters was broken, Fogel decided to prove as much and make a documentary film about his experience. His methodology: Dope himself up, compete in the world’s most grueling amateur cycling race—the week-long Haute Route traversing precipitous Alpine peaks—and complete testing protocol without detection. If an average Joe could beat the labs, he reasoned, any competent professional could surely dope with impunity.

To this day, Fogel frames his movie pitch as the athletic blood-doping version of the 2004 fast food exposé Super Size Me. But even in the most flattering light, the notion that an audacious, forty-something human lab rat could deal himself in to the high-stakes World Anti-Doping Agency (WADA) testing process and churn out an Oscar-winning, feature-length film seems pretty half-baked. A leap of faith was required for Impact Partners, a New York-based, social-justice documentary underwriter with which Fialkow is affiliated, to back the film. Even Icarus co-producer Dan Cogan, who rounds out the Impact team with James R. Swartz, calls Fogel’s pitch a “gonzo idea.”

Once again, Cutler explains why Fialkow would back such a longshot. “Taking risks, pushing the boundaries, spotting the opening, then putting his capital to work in a place where he thinks it’s effective—that’s very much like what David does every day at work,” says Cutler. “It’s a natural skill-set for him, especially if you add the creativity part. Venture capital is really quite creative, and that’s one of the reasons why David’s so good at it. His success as a film producer is about this confluence of mixing up really smart people, deploying capital, taking huge amounts of risk, being artistic, seeing something before other people do, and not giving a hoot whether people say it’s a dumb idea or not.”

“So often, the financier is looking over your shoulder. David is somebody who empowers people to do their best work and he’s someone who’s going to fight for you. You don’t get that every day in this business. In fact, you don’t get that any day. He’s truly inspiring and one of a kind.” —Icarus director Bryan Fogel

An entrepreneurial dynamo whose default tempo is somewhere between allegro and prestissimo, Fialkow was once described in a news article as a “Renaissance Man.” Yes, that’s with a capital “R” and capital “M.” Fogel calls Fialkow “a force of nature.” A former stand-up comedian who co-wrote and starred in the Off Broadway play Jewtopia, Fogel needs no prodding to elaborate: “David always believed in the project and did everything he could to support it, and he truly took on a position in the working environment that was way beyond that of an investor. He used his skills and connections and talents to help guide this film.

“What generally happens in these endeavors is that the business end encroaches on the creative, or the creative becomes all about the business,” continues Fogel. “So often, the financier is looking over your shoulder. David is somebody who empowers people to do their best work and he’s someone who’s going to fight for you. You don’t get that every day in this business. In fact, you don’t get that any day. He’s truly inspiring and one of a kind.”

Be that as it may, once Icarus was green-lit, neither Fogel nor Fialkow anticipated the maelstrom of corruption, suspense, secrecy, and danger that awaited.

Fialkow has put up some impressive totals throughout his career. While still in law school, he and Cutler founded the Last-Minute Travel Company specializing in steeply discounted vacations for students or others with flexible schedules. They launched the business out of their apartment in Allston and, by 1987, the company was operating out of Filene’s Basement as the National Leisure Group. The childhood friends sold the business in 1995 for $20 million. At the time, it was the third-largest provider of vacation packages in the US and was handling 135,000 bookings a year worth about $93 million.

Prior to founding General Catalyst in 2000, Fialkow co-founded and operated multiple enterprises ranging from travel, information services, and speciality retail opportunities to the consumer-direct and payment-processing industries. He also served as an associate at Thomas H. Lee and US Venture Partners. According to SEC filings earlier this year, General Catalyst now has $3.4 billion under its management spread across nine VC funds.

When it comes to film production, Fialkow is, undeniably, the guy who writes checks. But he brings artistic gravitas to the process that stretches well beyond the stroke of a pen. A sociology major at Colgate, Fialkow spent four months in London making films as part of the university’s multi-country Global Study program. Appalled by human rights violations he encountered while visiting South Africa, he founded the South African Committee upon his return to Colgate with the hope of effecting change from within. His cinematographic work in the UK earned him a grant to continue making films on his own. Fialkow believes in art for art’s sake, and he believes in paying it forward.

“We try to give as many people as possible the opportunity to be young filmmakers, young directors, or young producers, and to have their stories told. None of us has had overnight success. I think getting mentored, being creative, backing great talent and, perhaps most important, allowing a change of direction in the middle of the creative process as the ordinary course of business—that’s what produces the best outcomes,” Fialkow says.

“At the time we launched the project, we thought we were making a film about cycling and doping,” explains Fialkow. “It was going to be a movie about a guy who raced one year without drugs and raced the next year while doping. There was never any thought, discussion, vision, or belief of a Russia storyline. A lot of this was in 2015 and early 2016, before the [US] election and all the Trump and Putin stuff. We didn’t really know where things were leading, but over time, we realized there was this Russian angle. That was really, really significant for us. Then, it kept getting deeper and deeper and deeper. At that point, we realized that we had a better film on our hands.”

Deciphering what ultimately spawned Icarus requires a flashback to 2013. A year into his second stint as president, Vladimir Putin’s approval ratings were bottoming out. According to the Russian NGO Levada Center and the Pew Research Center, only 40 percent of Russians thought the country was moving in the right direction and about 60 percent believed economic conditions in Russia were “bad.” Just a half-dozen years earlier, in 2007, when Putin spearheaded Russia’s winning bid to host the 2014 Winter Olympic Games in Sochi, his approval rating had been 81 percent—the highest of any world leader.

As the 2014 Games approached, according to Icarus and corroborating reporting, Putin devised a scheme to return to preeminence with the Sochi Games as the driver. Allegedly, at the highest levels of the Russian government, it was decided that an unprecedented showing by the host country’s athletes at Sochi could ignite a flame of nationalistic pride and provide cover for Putin’s planned expansion of Russia’s strategic influence. The plan was to cheat.

Dr. Grigory Rodchenkov, director of the state-of-the-art and world-renowned Antidoping Centre Moscow, told team Icarusthat he was given brazen and astonishing instructions. Russian athletes who doped prior to international competition would no longer cycle off of drugs on a precise, personalized day—a “wash-out” interlude predetermined by laboratory experimentation—to avoid detection when tested. That protocol had been somewhat customary (subject to the constraints of existing science) among Russian athletes who doped, beginning in the 1950’s of the Soviet era and onwards. For Sochi, the Russian Ministry of Sport wanted designated athletes with promising medal prospects to keep doping and have their steroid-tainted samples given during Olympic competition automatically swapped for their own clean urine, secretly stored in the FSB (formerly KGB) Command Center adjacent to the testing lab. In effect: an elaborate, state-sponsored scam to inflate Russian medal totals.

According to Rodchenkov, in the dark of the night and undetected by both International Olympic Committee monitors and WADA inspectors, samples were switched. Russia won an unprecedented thirty-three medals and a record thirteen golds as host of the Sochi Games. Putin’s approval rating skyrocketed overnight. Coincidence or not, five days after the closing ceremonies, Russian troops entered Crimea, which was absorbed into the Russian Federation less than a month later. Later in 2014, Kremlin-backed militias and Russian military personnel occupied about 6,000 square miles of eastern Ukraine in a conflict that continues today.

Fogel acquired his own PEDs from an American “anti-aging” doctor, but he needed science to game the system and beat any drug test. After demurring Fogel’s 2014 request for guidance, a UCLA anti-doping researcher suggested he reach out to Rodchenkov, who was well known for his comprehensive expertise in anti-doping testing protocol. The two men met via Skype and before long, the Russian, apparently intrigued purely by the scientific exercise, agreed to be Fogel’s accomplice in optimizing his performance by pharmaceutical means.

Rodchenkov traveled stateside early in 2015 to oversee the start of Fogel’s six-month doping regime. He then smuggled the film director’s urine back to his Moscow lab and calculated Fogel’s proper wash-out date; in other words, when he had to stop doping to be undetectable during his Haute Route race in August. Initially viewed as a peripheral character in Icarus, Rodchenkov carries the plot. The Atlantic flawlessly described Fogel’s fun-loving, pet-worshiping, and quasi-paternal Russian co-star as “a dream subject—eccentric, garrulous, frequently shirtless, and immensely charming.”

The movie’s original storyline completely derailed, however, when Fogel failed to perform as expected in the Swiss Alps. Drug-free during the 2014 race, Fogel finished fourteenth. Largely due to a bike malfunction that left him unable to shift out of high gear for 100 kilometers, Fogel finished twenty-seventh in 2015, despite the elaborate cocktail of illegal drugs that had coursed through his veins during training.

“The race results were less than extraordinary, so we needed to pivot,” says Fialkow. “We made the decision when Bryan was still in Switzerland to send him to Moscow to film and interview Rodchenkov. That pivot turned into the movie.”

At this point, team Icarus was simply looking to beef up the storyboard and make the film more beguiling. But suddenly, the “eccentric” Russian scientist turned into “the Russian Edward Snowden,” as Fogel likes to say. Dr. Rodchenkov let Fogel follow him around with a camera and even welcomed him inside his Moscow lab. Then, he began spilling the secrets of the state-run criminal conspiracy to rig the 2014 Winter Games. That’s when things got pretty Zero Dark Thirty. “We realized he was not only the anti-doping Czar, he was also the doping Czar,” says Fialkow. “The irony of that was just incredible.”

It’s possible, even likely, that Rodchenkov felt the walls closing in on him before Fogel fell behind in the Alps. In December 2014, a German news documentary had issued a report about alleged state-sponsored doping in Russia. In November of 2015, after Fogel’s visit to Moscow, an eleven-month WADA probe into the Russia allegations led to the suspension of the Moscow’s anti-doping lab accreditation. Rodchenkov was forced to resign, and Putin held a press conference to deny any wrongdoing while incongruously pledging to punish anyone responsible for any violations. All the while, Fogel kept Skyping with Rodchenkov, and kept filming.

Within days of abdicating his post, Rodchenkov was tipped off by a friend in the government that his life was in danger. Team Icarusflew him to Los Angeles, two of Rodchenkov’s associates eventually turned up dead under suspicious circumstances, and Putin labeled the scientist “an enemy of the state” in the media.

“Over the next seven months … the team moved [Rodchenkov] to four different safe houses,” Fogel told Vanity Fair. “We moved our production offices four times and worked with him over those months to compile his evidence, translate [it], and bring that evidence to the New York Times, which published his diaries … we weren’t really thinking about making the movie. This was the journey we were on and we wanted it to be documented.”

Team Icarus used disposable cell phones to communicate about the film, stashed backup hard drives of footage around the country (believing the editing room in Santa Monica and Impact Partners’ offices in Brooklyn were unsafe) and, throughout production, never shared cuts or communicated in any manner about the film using the Internet. Fialkow and Fogel stayed as mobile and inconspicuous as possible, coming together in Boston, Martha’s Vineyard, New York, London, Los Angeles, San Francisco, Tampa Bay, and Yellowstone Park, among other locales. Because of these limitations, Fogel was still making edits to the final cut the night before Sundance.

“We were in daily, real-world crisis management that went so far beyond filmmaking,” recalls Fogel. “David never once backed down or cowered, but was there helping me and pushing me forward every step of the way. He’s an incredible, incredible human being and partner.”

Rodchenkov’s allegations and his revelations to the Timesin May 2016—a step Fialkow believed was critical in order to fully vet the Russian’s story—became the basis of a shocking report by WADA in July, which exhibited proof of at least 1,000 Russian athletes doping across thirty sports from 2011 to 2015. In short order, Russian authorities charged Rodchenkov as a drug trafficker and sought his extradition (though no such agreement exists between the two countries). US authorities quickly put Rodchenkov in the federal witness protection program, having gathered intelligence of a mounting Russian threat to his well-being.

Icarus became commercially available last August on Netflix, which purchased the movie for $5 million, a stunning sum in the world of documentary film. Fialkow says the profit will be used to finance future whistle-blowers. Today, the story of Grigory Rodchenkov is still being told. Fogel and the asylum-seeker’s lawyer can only contact him through an intermediary.

Moscow has issued a warrant for the former lab chief, which could affect his immigration case in the United States. Rodchenkov’s wife and children, who still live in Russia, have had their assets frozen, property seized, and their passports temporarily confiscated. Russia continues to deny allegations of widespread doping, even in the face of sanctions against its athletes in both Rio and South Korea.

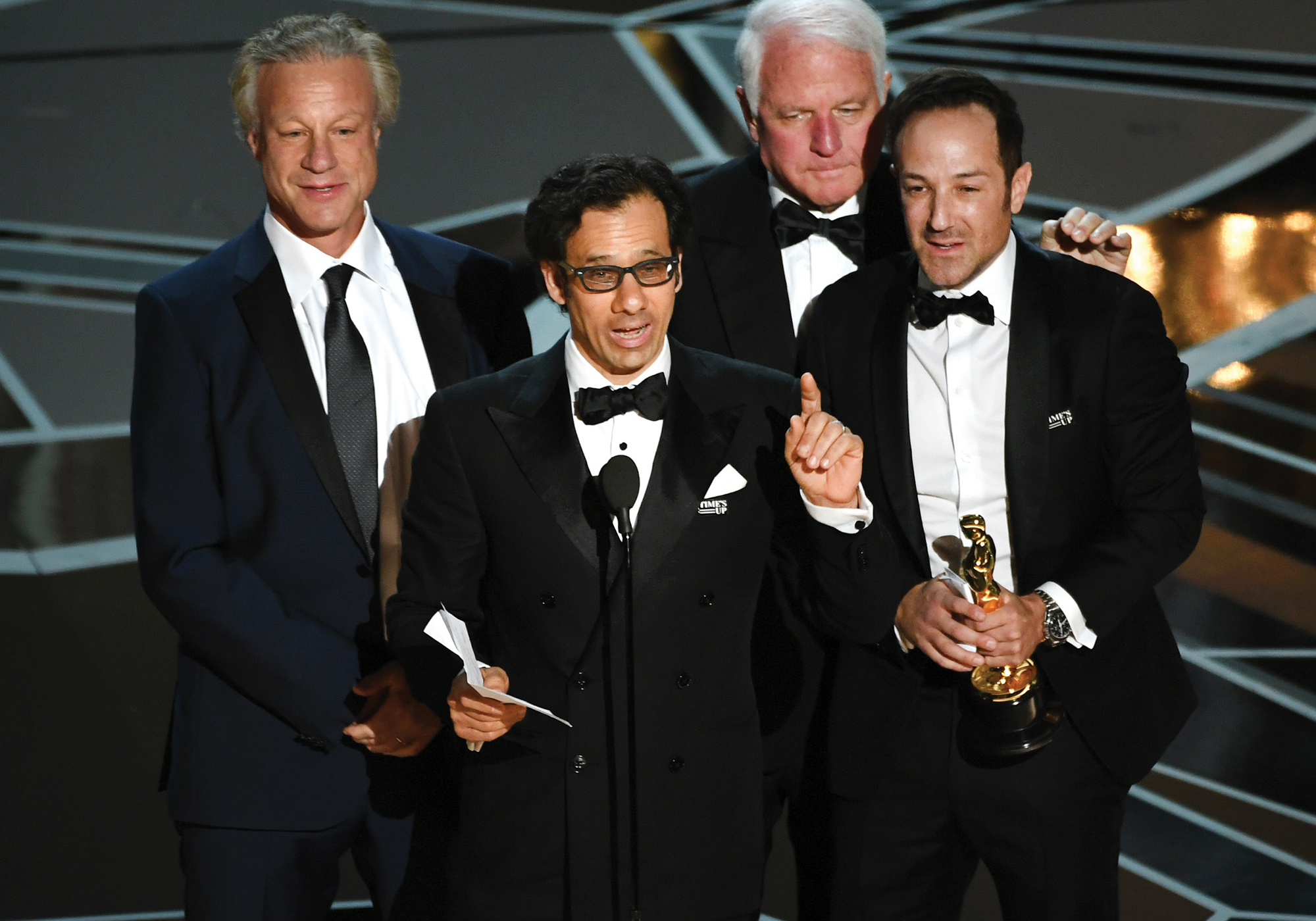

Given the downright radioactive half-life of the Icarus project (now five years on from when Fogel dreamed it up), the 90th Academy Awards were as much a respite as they were a celebration for the men who made the movie. Fialkow calls the Oscar win “very lucky.” Cutler sees it differently.

“Look, David has a really high moral compass and he’s really creative,” says Cutler. “He’s a collector of great talent. And he knows how to put those people in a room and help them work together, even if they never knew one another before that moment. So, is it a surprise to me he won an Academy Award? Yeah, in so far as it’s a relatively small group of people who get to win those. But it’s totally unremarkable to me that David does something outstanding whenever he puts his mind to it.”

While it is surely bad form to ask an Oscar winner how he plans to follow up an Oscar-winning project, it’s also hard to resist inquiring. Can Fialkow catch lightning in a bottle twice? It turns out Impact released a film in May on Showtime called The Fourth Estate, which chronicles part of the US election cycle in 2016. The documentary has Fialkow “very excited.” The company also has a forthcoming release later this year on what he calls a “similarly timely topic.”

That said, the newly minted Academy Award producer isn’t about to make any predictions.

“We were very fortunate with Icarus because you could never reproduce the timing of two Olympic Games and a Russia scandal, and have the film come out when it did,” he says. “I was confident we had made the best movie we could, you just never think that something like this is gonna happen. We’ll see what happens on the next two. One thing is for sure: It’s going to be interesting.”