Hope has many adversaries, but few greater than the metallic clink and jangle of human bondage. On April 23, 2019, Christopher “Omar” Martinez walked out of the Hampden County Superior Courthouse as a free man for the first time in almost twenty years. Tears streamed down his face as Omar swept his sister up in a bear hug and then held onto his father, both men sobbing, for what seemed like minutes. A hallway full of Boston College Law students, attorneys, and spectators heard cries of delight as Omar facetimed his mother in Puerto Rico and told her that his conviction and life-sentence had finally been overturned after years of proclaiming his innocence.

Omar was only nineteen years old when his friend and co-worker Eddy Reynoso was shot and killed in Springfield, Massachusetts, on October 25, 1999. Two days after the shooting, Omar found himself being interrogated by the police for the first time in his life. He was alone, confused, and terrified. Following seven hours of interrogation, Omar, who spoke only Spanish, signed a confession written in English. After a six-day trial in 2002, he was sentenced to life.

“I had given up,” Omar says now. “I lost trust in [the system]. I lay there at night thinking on my mom and crying. I was like, ‘Well, this is it. This nightmare has become a reality and there is nowhere to go from here.’”

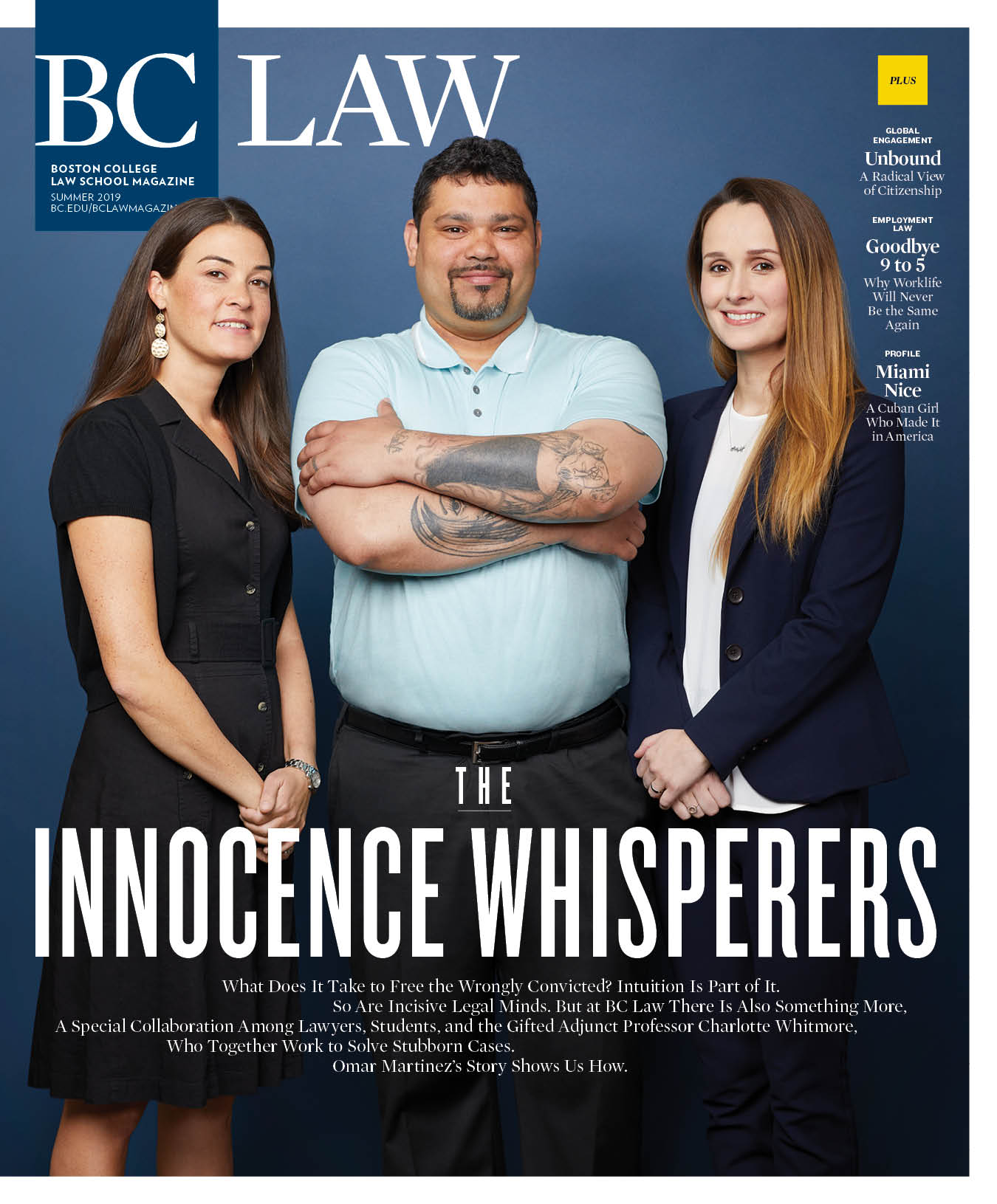

The Dream Team

Boston attorney Chauncey B. Wood, of Wood & Nathanson, was first appointed to represent Omar in 2002. He believed in Omar’s innocence but was unable to persuade the state trial or appellate courts to grant relief or even funds to investigate the holes in the prosecution’s case. Without resources to investigate, the case seemed to be at a dead end.

That changed in 2015 when Wood helped persuade the Committee for Public Counsel Services’ Innocence Program (CPCS IP) that Omar’s case merited reinvestigation and CPCS reappointed Wood to the case. Because the case required extensive reinvestigation and litigation, the CPCS IP suggested that Wood partner with BC Law Adjunct Professor Whitmore and the BC Innocence Program (BCIP), an interdisciplinary legal educational program founded and directed by Associate Clinical Professor Sharon Beckman. Her vision was for BC Law students to study the problem of wrongful convictions in the classroom and work in the clinic to help remedy and prevent these injustices.

Wood, Whitmore, and the entire BCIP team partnered for four years, collaborating on briefings, motions, and strategy. “Representing Omar under Whitmore’s supervision has been an extraordinary experience for the students,” Beckman observed.

In the courtroom, advocating for her incarcerated innocent clients, Whitmore is reserved but tenacious. Whitmore’s parents met while at Harvard Law School. She herself earned her BA, an MEd, and her JD at Ivy League schools. Whitmore captained the Dartmouth squash team and to this day is fiercely competitive in racket sports. Her competitive nature is evident in the courtroom as well. Whitmore has a quiet certitude about her, but her preparation and advocacy are intense. Once she sets herself in motion, she will not stop.

“The most fraught component of a legitimate post-conviction innocence claim is navigating the human element. Gaining the confidence of a potential exoneree, building the trust of witnesses, supporting the defendant’s anguished family, and staying vigilantly considerate of victims’ relatives,” explains Supervising Attorney and Adjunct Professor Charlotte Whitmore.

“For as long as I can remember, fighting for underserved populations was something I wanted to do,” says Whitmore, who witnessed an Innocence Project courtroom exoneration at twenty-two as an intern in New York, but still thought she wanted to become a teacher in an inner-city school. “My dad definitely instilled that value. He was the first in his family to go to college. He always stressed how my grandfather, despite having very little money, would give money to almost anyone who needed it.”

After earning her JD with honors at Penn Law, Whitmore clerked for the Honorable Anita B. Brody in the Eastern District of Pennsylvania and the Honorable Marjorie O. Rendell in the United States Court of Appeals for the Third Circuit. Subsequently, Whitmore was awarded an Equal Justice Works Fellowship to become the first staff attorney for the Pennsylvania Innocence Project. Upon winning an exoneration and release in a precedent-setting case there, Whitmore joined Beckman in the BC Innocence Program.

“All along the way, I had almost exclusively really smart and strong female mentors and supervisors,” she says. “One after the other, these impressive females who were a little bit older than me, who were simply amazing, allowed me to learn from them. That’s special and unique and played a large part in how I approach my work.”

Omar’s case consumed thousands of hours of factual investigation, briefing, argument preparation, and litigation by BCIP staff and students. Whitmore received prolific support from director Beckman, from Assistant Clinical Professor Claire Donohue, who handled the social work side of things, and from more than a dozen undergraduate interns and BCIP students. Most prominent among them were law student Lauren Rossman ’19, who worked side-by-side with Whitmore for almost two years, and BC School of Social Work student Parker Lawrence, who created Omar’s exoneree re-entry plan under the supervision of Donohue.

Inside Associate Justice John. S. Ferrara’s courtroom in the Hampden Superior Court in Springfield this past April—233 months into Omar’s prison term—Whitmore and Wood argued that, based on newly discovered evidence of innocence, justice was not done in Omar’s case. Judge Ferrara agreed and granted the defense motion for a new trial, thereby vacating Omar’s conviction. Omar was released the same day and was able to finally start to re-build his life free of any criminal convictions.

Seeds of Doubt

Massachusetts Rule of Criminal Procedure 30(b) authorizes a judge to grant a new trial any time it appears that justice may not have been done. A judge may grant a new trial if newly discovered evidence “casts real doubt” on the verdict, meaning that (1) the new evidence would have probably been a real factor in the jury’s deliberations, (2) the result of the trial might have been different, or (3) the defendant was deprived of a substantial ground of defense.

In 2002, the Commonwealth’s theory at trial was that Omar killed Eddy because of a dispute over a young woman named Gricela Gonzalez. She testified for the prosecution and told the jury that Eddy had been teasing Omar about a poem that Omar had written for her. In her statement to Springfield police, Gricela also described an altercation two days before the murder between Eddy and Gricela’s sister Jackie. That day, when Eddy started teasing Gricela, Jackie defended her by taking a swing at Eddy and threatening him with bodily harm. Omar, who was present at the dust-up, stepped in to defuse the situation.

Gricela’s testimony about an alleged motive, together with Omar’s confession, written in English, was enough for the jury to find him guilty. The Commonwealth presented no physical evidence or eyewitness testimony tying the crime to Omar. In the ADA’s closing argument, she encouraged jurors to rely on the confession alone without corroboration. Ultimately, the jury did just that.

The case, however, was riddled with intrigue, unanswered questions, and evidence that the jury never heard. The BCIP investigation eventually provided the elements that Omar and his defense team had been searching for.

Among them was the statement of the alibi witness, a 15-year-old friend of Omar, who signed a document written in English saying that Omar shot Eddy. Police used it to persuade Omar to sign a confession, but that statement was not used as evidence at trial, and the alibi witness did not testify.

There was the interrogator. He questioned Omar’s alibi witness and translated the exchange from Spanish to English. It later came to light that the interrogator may have had a significant conflict of interest.

There was the Holyoke shooter. Twenty-six hours after Eddy was murdered, a Latin Kings gang member shot a man in nearby Holyoke with the same .38 caliber revolver used to kill Eddy. A cab driver identified the Holyoke shooter as a man he picked up near Eddy’s apartment the night of Eddy’s death.

There was also the ear-witness to Eddy’s murder.

The Puzzle Pieces

In July of 2015, Wood applied for and received funding from the New England Innocence Project’s (NEIP) Running for Innocence Fund to hire a private investigator to locate two key witnesses in Omar’s case who never testified at trial: the alibi witness named Carlos “Carlito” Rodriguez, and the exculpatory ear-witness named Wilbert Diaz.

BCIP joined Wood in August 2015 and plunged into an exhaustive post-conviction investigation of the case. Within three months, the team shared in a big breakthrough when the private investigator secured a signed affidavit from Rodriguez stating that he was with Omar the night of the murder and that Omar did not shoot Eddy Reynoso. Rodriguez also recanted his 1999 police statement, in which he had inculpated Omar, claiming that police physically coerced him and threatened him until he signed the statement.

Wilbert Diaz was Eddy’s neighbor, and he told police immediately after the murder that the killer asked “Are you Eddy?” before firing his gun, indicating that Eddy and his killer were strangers, whereas Eddy and Omar were friends. Diaz knew Omar and was with him just hours before the murder. Diaz was positive the killer’s voice was not Omar’s and he would have testified as much at trial, but neither the prosecution nor the defense asked him to testify.

“No innocent person should suffer as Omar and his family have these past twenty years. Our criminal system is broken, but our students learn they can be agents of change,” says BC Innocence Program Director and Associate Clinical Professor Sharon Beckman.

At the time of trial, Omar’s defense attorney couldn’t find Diaz because he was searching for him at an outdated Springfield address. The trial assistant district attorney twice served Diaz with subpoenas at his new Worcester address she’d obtained at least eighteen months prior to Omar’s trial. She also met with Diaz personally to review his testimony and, according to Diaz, told him that he wouldn’t have to testify. The Commonwealth’s pretrial witness list included Diaz’s outdated address. The ADA never informed the defense of Diaz’s whereabouts and did not correct the defense’s own use of Diaz’s incorrect address in filings.

In addition, the BCIP team scoured social science research on false and coerced confessions, a field which had principally evolved after Omar’s 2002 conviction. Omar was a teenage Spanish-speaker when he signed the typed, six-page confession written in English. The confession was produced by a detective who translated Omar’s oral Spanish into written English, and then translated the English text orally into Spanish for Omar’s review and approval.

With financial support from Running for Innocence and a federal grant awarded to CPCS, BCIP, and NEIP to investigate innocence cases, the defense team hired expert witnesses, procuring an affidavit from a practiced psychologist, who concluded that Omar’s personality characteristics and intellectual deficits at nineteen made him particularly vulnerable to giving a false confession. They also secured a report from an expert in police investigative procedures and false-confession risk factors, who analyzed BCIP’s comprehensive curation of evidence and concluded that Omar’s confession and his companion’s statement were unreliable.

Amid the line-by-line dissection of a case, it’s possible to become desensitized to the emotional intensity of the factual record. “In the moment, you can forget what this is all about, but then you burst into tears because a young person was murdered,” says student Rossman, who, like Whitmore, seems outwardly imperturbable. “What happened to Omar afterwards is tragic, too. This will never stop being tragic.”

Rossman, twenty-eight, flourished under Whitmore’s tutelage and mastered the skills of factual investigation and legal advocacy, a process punctuated by oases of euphoria or setback amidst a sea of drudgery.

Rossman’s own experience of being marginalized growing up fuels her desire to spend her career fighting to exonerate the wrongfully convicted. The child of a single mother raising a family within an affluent community, Rossman was socially ostracized by her peers and presumed by school officials to be a troublemaker. In eighth grade, she was falsely accused of using drugs by the principal. On another occasion, she was the suspect in a school vandalism incident, prompting an interrogation, a search of her backpack, and an analysis of her penmanship by a handwriting expert.

Rossman’s commitment to seeing justice done to others made her the quintessential Watson to Whitmore’s Holmes in Omar’s case.

Everyone working on a post-conviction relief case shares in the inexorable march of time-served by the defendant as a case is stripped to its bones, then reanimated. “There are so many frustrations and ups and downs,” explains Whitmore. “The most fraught component of a legitimate post-conviction innocence claim is navigating the human element: gaining the confidence of a potential exoneree, building the trust of witnesses, supporting the defendant’s anguished family, and staying vigilantly considerate of victims’ relatives.”

Following a separate investigative thread, Rossman volunteered to go to Florida to interview Gricela Gonzalez, one of the sisters who had gotten into the altercation with Omar and Eddy a few days before Eddy’s murder. Gricela told Rossman that she’d always believed Omar was innocent, but declined to go on the record, or say why she thought so.

Rossman, an intuitive fact-finder, fretted about the conversation. What basis did Gricela have for her belief? The third-year law student, who labored over the case the entirety of her 2L and 3L years, and the summer in between (the first such BCIP student to do so), dug in. Through extensive research, Rosssman discovered that Gricela’s husband is step-brothers with one of the Springfield police officers who worked on this case, the interrogator, Officer Francisco Otero.

“In the moment, you can forget what this is all about, but then you burst into tears because a young person was murdered,” says student investigator Lauren Rossman ’19. “What happened to Omar afterwards is tragic, too. This will never stop being tragic.”

During the police investigation of Eddy’s murder, Officer Otero, who was neither a detective nor assigned to the homicide unit, but rather an on-duty Springfield Police Department uniformed patrolman, stepped away from his normal duties to grill Rodriguez about an hour after Gricela completed her own statement to police.

Just a few months after Eddy’s death, Officer Otero’s step-brother moved in with Gricela. They conceived their first child three or four months after the murder. Their second child was born three months before Omar’s trial and the couple was married thirty days after Omar’s conviction.

A reasonable jury in possession of these details might question whether Officer Otero’s priority was to protect Gricela instead of identifying the real killer. Jurors might also speculate that Gricela came forward preemptively to protect herself and her sister Jackie, who had ties to the Latin King gang. This logic, while strong, was about to get even more sound.

Rossman by then had a profound sense of personal obligation: “The more we investigated, the more we realized this was a huge miscarriage of justice. I kept thinking: Every moment I’m not working on this case, he’s just sitting there, waiting for you to do something.”

On October 18, 2018, exactly 990 weeks to the day Omar woke up behind bars for the first time, Rossman became aware of an inmate at MCI-Norfolk named Ramon Santana. Santana is the half-brother of Kelvin Gutierrez, the man who committed the murder in Holyoke twenty-six hours after Eddy’s murder, using the same .38 caliber weapon that was used to shoot Eddy. Rossman and Whitmore went to meet with Ramon Santana.

According to Rossman’s signed affidavit, when Whitmore asked Santana if he knew anything about Eddy Reynoso’s murder, “Mr. Santana’s eyes immediately filled with tears and he lowered his head as he informed us that [Omar] was completely innocent.” When asked how he knew that, Santana responded, “I’ll just tell you this: Eddy tried to shut the door in my face.”

Santana, who was affiliated with the Latin Kings gang at the time, confirmed that he shot Eddy along with an unnamed accomplice over “women and relationships.” Santana said he gave the .38 revolver to his accomplice the following day. Santana stated that Omar was completely uninvolved in Eddy’s murder.

“Sitting in that prison visiting room with Lauren and Mr. Santana as he gave us a full confession with details of the crime, that was a pretty big moment,” says Whitmore. “After all these years, we felt like we had finally solved the mystery of who shot Eddy Reynoso and how [Kelvin] Gutierrez got the gun used in the Holyoke murder.”

The Decision

“Because we dig so deep and have the team talents to really pick cases apart, reinvestigate, and put them back together, we are constantly discovering new legal or factual arguments,” says Whitmore. “To actually break apart a case and see how a wrongful conviction happens and, frankly, how easily it can happen, is shocking. There’s not just one road to the right result or to justice. There are many different pieces along the way that you have to uncover, and to do that, you need a team working on the case.”

Omar’s defense team petitioned Judge Ferrara to consider numerous factors in its motion for a new trial based upon newly discovered evidence: (1) Wilbert Diaz’s testimony that the shooter was not Omar; (2) that the Commonwealth was aware of ear-witness Diaz’s contact information, but withheld this exculpatory information from the defense; (3) the trial defense attorney’s ineffective assistance of counsel for promising the jury that Diaz would testify that the shooter’s voice was not Omar’s when counsel had not interviewed or located Diaz; (4) expert testimony explaining why Omar’s confession was unreliable, (5) Rodriguez’s alibi testimony and recantation of his inculpatory police statement; (6) police testimony regarding Rodriguez’s interrogation and evidence of a police conflict of interest; (7) newly discovered alibi evidence from Rodriguez; and (8) Ramon Santana’s confession.

On April 23, after post-conviction oral arguments and three days of evidentiary hearings, Judge Ferrara calmly delivered his ruling granting the defense motion for a new trial and vacating Omar’s conviction. Shortly afterward, Omar was released.

It was 11:39 a.m. In the span of a few syllables, Omar was free, entitled to a new trial and, once again, presumed innocent. (On June 10, the Commonwealth announced it would not appeal the ruling vacating the conviction.)

In the end, the court ruled that the “confluence of factors [the defense] has presented demonstrate … a substantial risk that [the defendant’s] convictions may not have been just.” Judge Ferrara was particularly persuaded by the credibility of the new ear-witness testimony, the circumstances of Omar’s confession in the context of scientific evidence about interviewing tactics used by police to elicit false confessions, defense counsel’s promise to deliver a witness—Diaz—whom he had not found, and the original ADA’s “unexplained and perhaps inexplicable” failure to alert the defense to witness Diaz’s whereabouts prior to trial.

“Honestly, I had to read the transcript to remember what the judge specifically commented on from the bench,” admits Whitmore. “After he granted the motion my brain … well, I was a total mess. My focus was less on what the exact holding was. I didn’t care at that point. I was thinking, ‘How are we going to get him out today?’”

Wood, too, was elated while contemplating Omar’s next steps. “Omar being released is a huge moment, but it’s just the beginning. It’s tomorrow and the next day and the day after that where BCIP is so critical to his success after this moment. As a private lawyer, I can’t do those things that are necessary to get a heavily institutionalized, wrongfully convicted defendant where he needs to go,” he says.

“That’s where,” Wood continues, “the full scope of what the BC Law innocence clinic can do—the intensity of the students helping the reinvestigation of a case, the social workers designing the exoneree re-entry plan, gifted attorneys like Charlotte and Sharon writing a ton of legal memos—and all that the clinic effectuates becomes cutting edge. Law school clinics like the one at BC are at the vanguard of client-centered representation that is crucial to post-conviction relief for the innocent.”

Beckman agrees that this is just the beginning. “BCIP will continue collaborating on innocence cases like Omar’s and on law and policy reforms to remedy and prevent wrongful convictions,” she says. “No innocent person should suffer as Omar and his family have these past twenty years. Our criminal system is broken, but our students learn they can be agents of change.”

For his part, Omar says publicly that he harbors no ill will or resentment. And there is no denying that his focus is elsewhere.

“I have a second family now—Mrs. Charlotte and her team—that I love and respect and have done everything for me,” he says. “I’ve started to do the work to show them, not with words but with actions, the appreciation I feel. When you haven’t committed the crime, I think you can leave peace within you. To keep the anger or grudges or remorse? I think that’s wrong. I prefer to forgive and to listen and do my best to have the dialogue.”