Growing up, Jazmine Banks, a young woman from San Francisco, was placed in more than twenty foster homes, had a child before she turned eighteen, and was housed by the domestic violence system in a place that was dangerous for her and her daughter. “For so long I thought I was the only person going through this,” she says. “A lot of youth have had the same exact experiences that I have had. That’s what made me want to stand up for people…to use my voice for power…especially for chocolate women.”

Banks found that voice in I Am Why, a kind of startup advocacy group with a national reach that BC Law Professor Francine Sherman ’80 began in early 2017. It embodies two of Sherman’s long-held ideas: that social policy should be made with the full participation of those who have to live with it and that the primary purpose of lawyers who work with social change movements—popularly known as movement lawyers—should be to encourage and support those who traditionally have been shut out of decision-making.

I Am Why grew out of Sherman’s directorship of the Juvenile Rights Advocacy Project, a BC Law School clinic, and her work on the 2015 monograph Gender Injustice, which she co-wrote with Annie Balck, a former BC Law student and now a lawyer who works with I Am Why and other social change groups. The monograph’s main thrust is that juvenile justice systems were designed—for the most part, poorly designed—for boys, and work even worse for girls, ignoring things like girls’ higher rates of trauma, their greater vulnerability to family conflict and sexual abuse, and the enormous importance of relationships in the lives of girls and young women.

What if girls and young women, including those with experience in the system, helped shape juvenile justice policies and those of other government programs that serve people like them, including the child protection and education systems? Would the policies better fit girls’ and young women’s needs?

To answer the question, Sherman has been helping to organize workshops and to recruit to I Am Why young women who have an interest in activism and experience with different forms of oppression. Some of the recruits have been involved in the juvenile justice and child welfare systems; some have experienced homelessness and endured gender-based violence; some are single mothers. Others have had none of those experiences but suffer gender-based oppression in their everyday lives. The vision is to build “young women’s individual and collective power,” Sherman says.

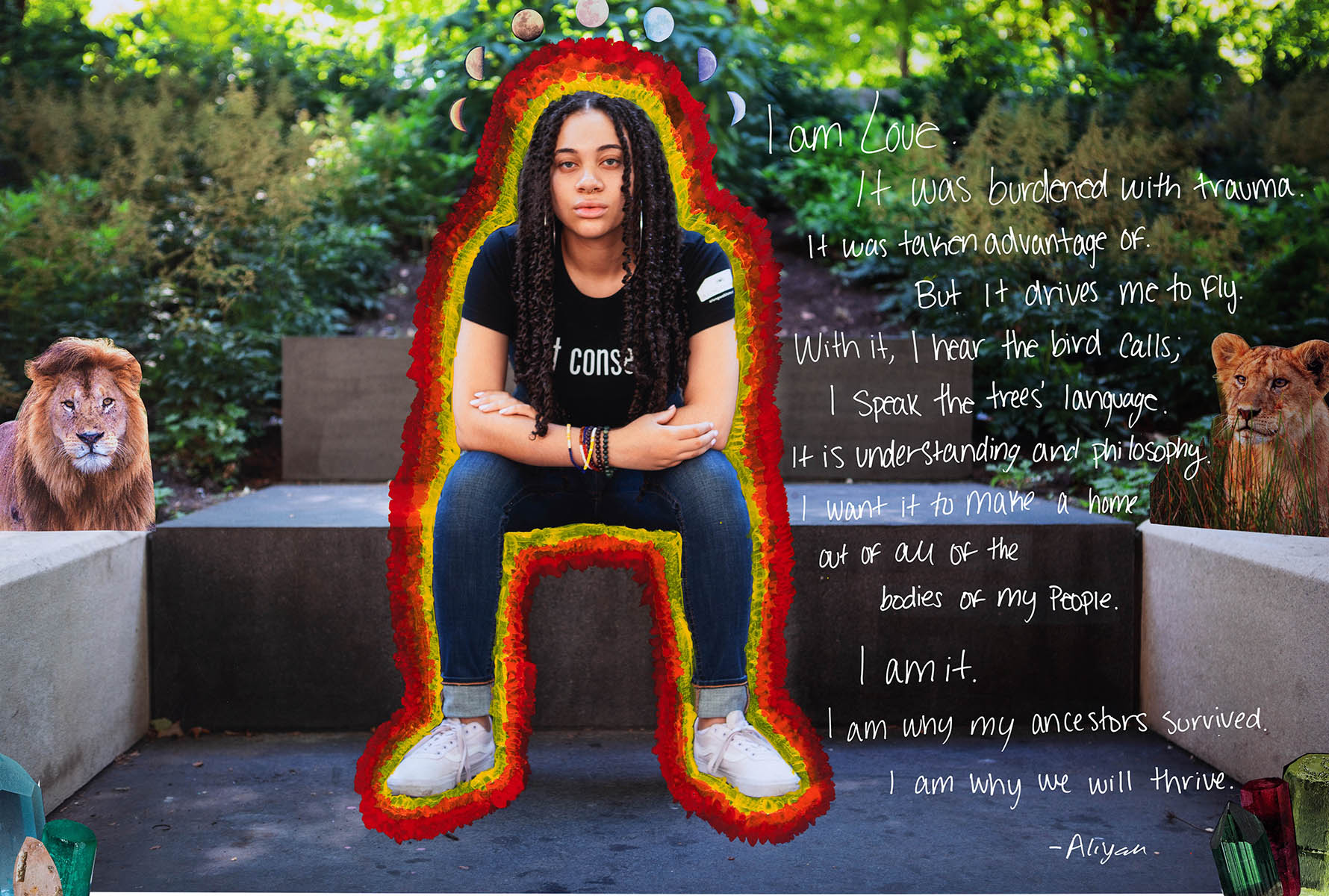

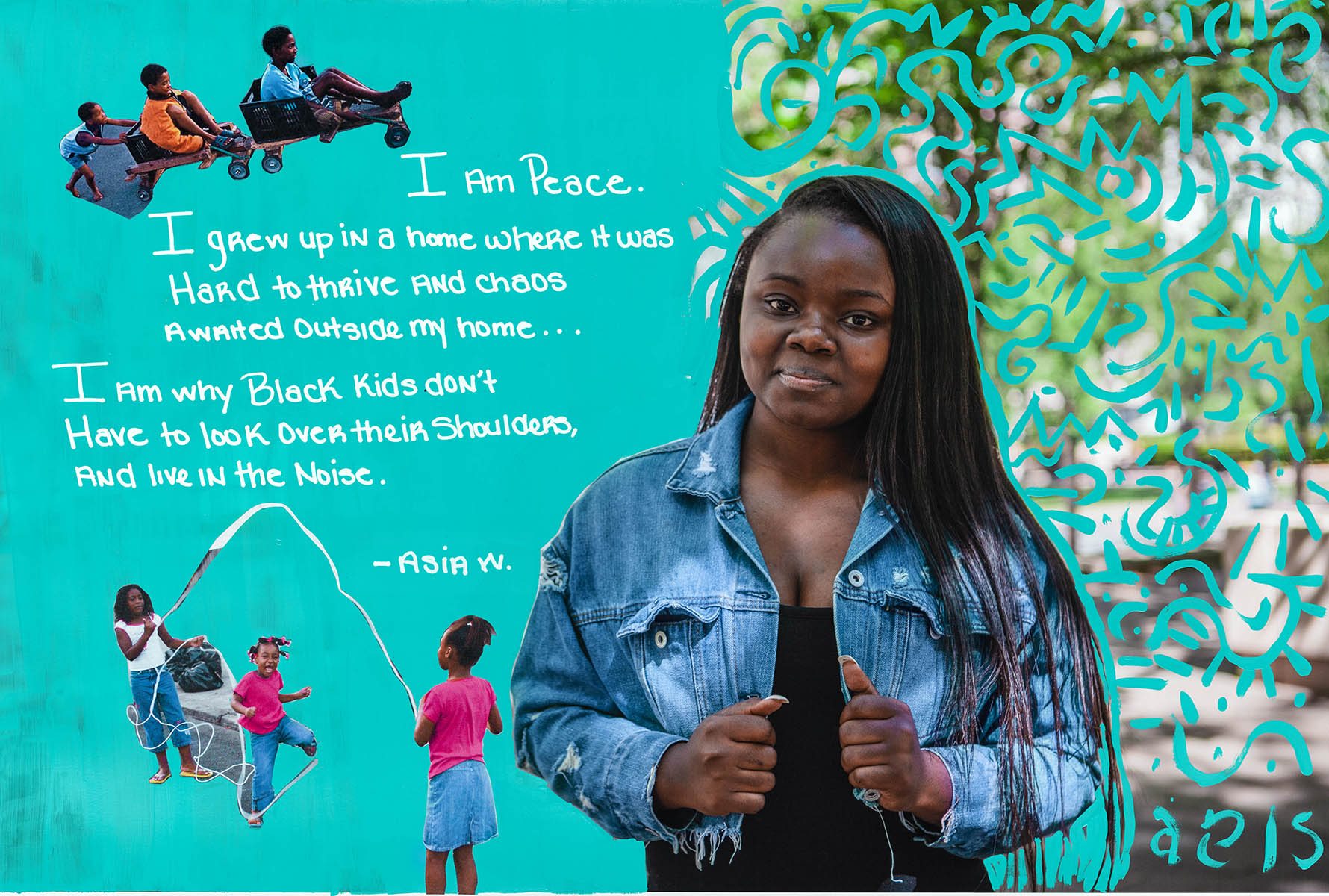

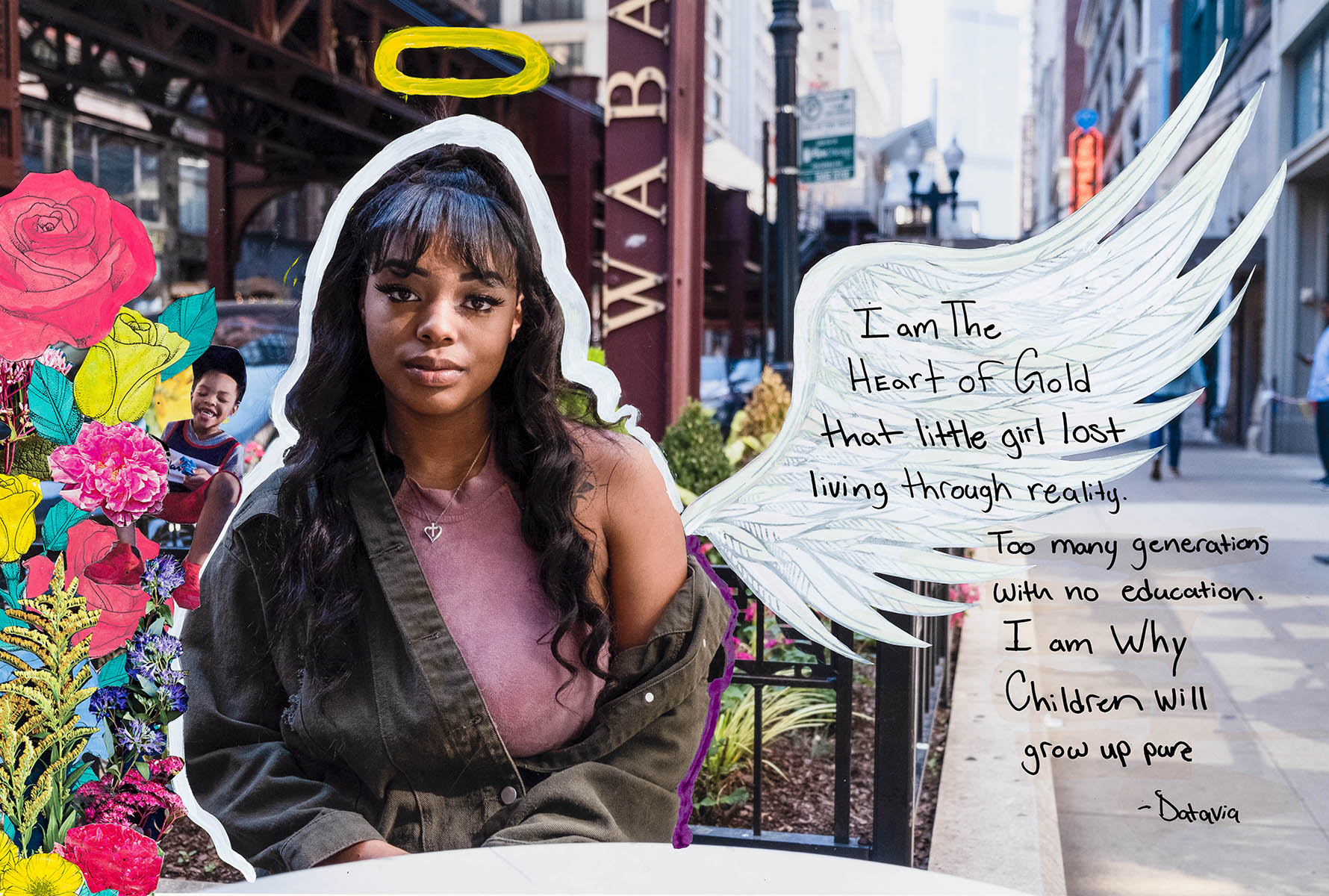

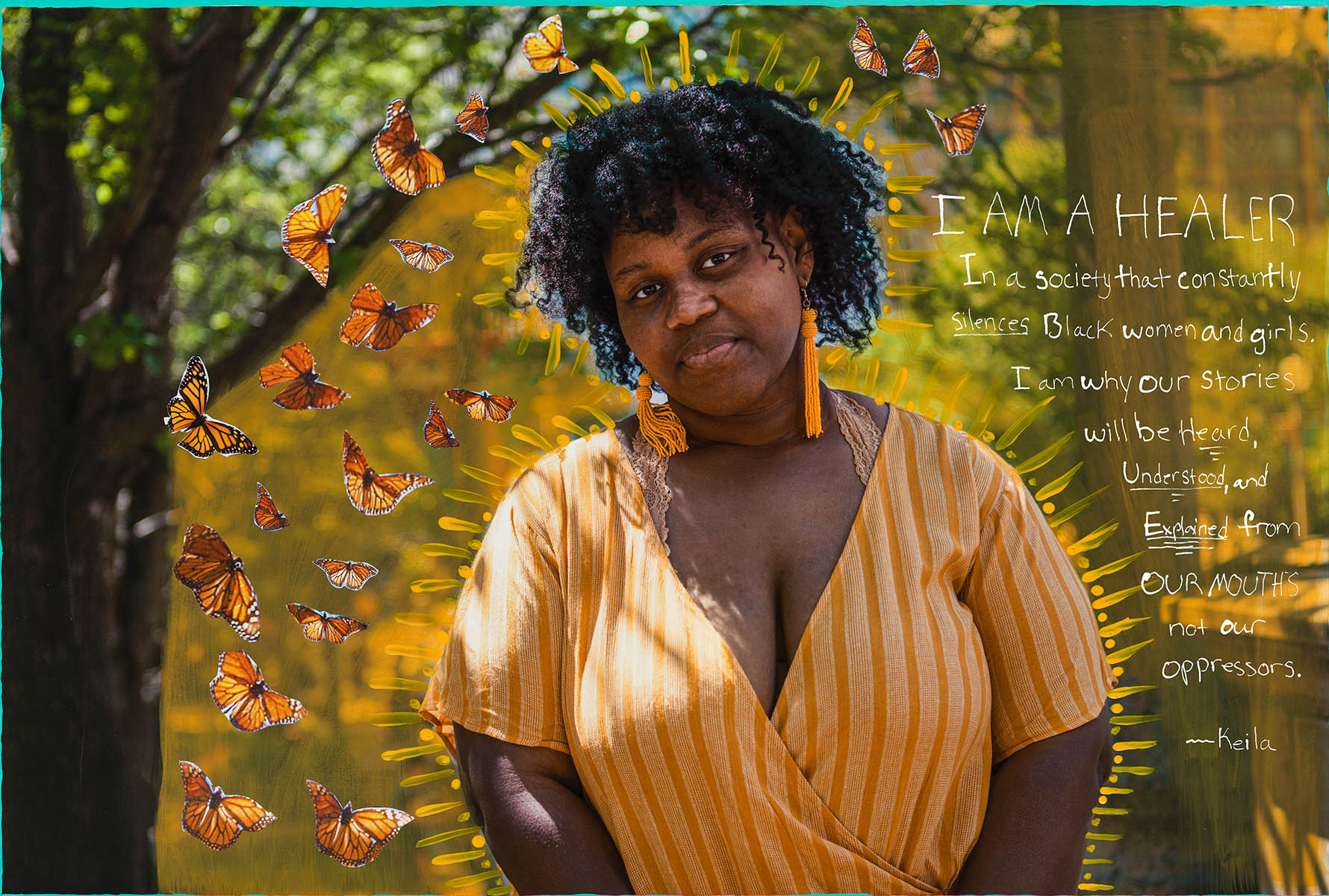

Jazmine Banks was one of those recruits. In 2018 she participated in the I Am Why San Francisco workshop in partnership with the Young Women’s Freedom Center. She and nine other young women wrote and designed photo collage self portraits and discussed, as she recalls it, “What do we imagine and what do we see in the future for girls growing up like us?”

Today, Banks is an I Am Why consultant on issues related to motherhood, self-determination, and safety. Marshaling various communications resources—a video of her on the I Am Why website, brochures connecting her experience to research, and video conferencing—she has begun working with Massachusetts programs and young mothers across the country to identify policies and practices that can give young mothers the power and support they need for their children and themselves.

In the meantime, recruiting to I Am Why continues. Newcomers are interviewed in order “to dig deeper into the content of the change they would like and to really understand what they see as positive change,” Sherman says. Advocacy training workshops have taken place in New York, Boston, Atlanta, San Francisco, and Chicago, and workshop alumnae, organized into a “curriculum team,” are currently working to put the workshops online, where they can be customized and accessible to young women and young women’s programs nationally. Other teams are focusing on curating exhibits that connect young women’s art to local issues, and conducting research to connect their experience to policy. A fourth team, comprised of workshop alumnae who are mothers, will be developing policy and practice ideas for young mothers. Additional teams will be added as needed.

What if girls and young women, including those with experience in the system, helped shape juvenile justice policies and….government programs that serve people like them?

A lot of what has emerged in the workshops and interviews touches on how systems try to stifle what girls and young women see as their own best qualities. The system, Sherman explains, often turns traits like outspokenness, courage, strength, resilience, and self-determination into negative qualities that should be shut down, not nurtured.

In I Am Why, Sherman and Balck are practicing movement lawyering, in which lawyers are there not to set an agenda or serve as the movement’s public face but to perform other useful but less dramatic tasks behind the scenes.

Sherman is doing this, in part, through pedagogy, teaching BC Law students who are considering careers as movement lawyers to see themselves as value-added and not as the center of the movement.

Balck sees her role as “helping craft a message but not deciding what the message is.” Crafting the message of I Am Why itself includes seeking out social science research that supports the young women’s calls for change. “Our systems are used to functioning in a certain way,” Balck explains. “What we’re trying to show [public policymakers] is that what they’re doing now is not effective—that it’s not a good use for the taxpayers’ money, that it’s not good for reducing crime, that it’s not good for getting young women to change their behavior.”

Balck and Sherman, along with a professional writer, also tailor the group’s message to an audience of agency heads and officeholders by connecting it to data and other research and translating it into “language that systems will hear,” says Sherman. All of this is done with an eye toward persuading the powerful to share some of their power with young women and girls. For that to happen, of course, the powerful need to be exposed to the message, and Sherman has been providing them with I Am Why brochures and other materials, including videos, postcards, presentations, poster art, and research bibliographies.

The effort is in its early days, but system-involved girls in Massachusetts have used an I Am Why brochure recently to argue for more equal educational opportunities for girls of color. I Am Why materials are also being distributed in a campaign by the Young Women’s Freedom Center—the San Francisco group involved in the I Am Why workshop that recruited Banks—to end the incarceration of girls, replacing juvenile jails with community-based programs.

Over last December’s holidays, the center sent I Am Why postcards of support decorated with the members’ art to incarcerated young women in California. One postcard’s author, Lole Kalani “K.I.” Finao, said, “…when you read the message you automatically feel supported, and when you see the image on that IAW postcard you see determination, hope, resiliency, and you see you. In the words of one of my center sisters: ‘No one comes for us, so we come for us.’”

In November, Sherman spoke on movement lawyering to the law school’s juvenile rights clinic, which was being run during fall semester by Visiting Professor Jessica Berry. Berry invited Sherman to speak so as to give students a broader context for their work in youth justice systems. “Many of our clients are involved in several systems—juvenile justice, mental health, education, child welfare,” Berry says. “We’re focused on how to help little Jennie navigate the system, but I also wanted our students to think about how well the system is working for our clients and their families, and if it isn’t working well, how do we change that?”

Student Accursia Gallagher ’21 came away from Sherman’s class impressed with the client-centered nature of movement lawyering. “In some kinds of lawyering, “Gallagher says, “you tell your client, ‘don’t talk,’ but not in movement lawyering, where the client has to be the face of the movement.” Classmate Caitlin Maloney’s takeaway was that with movement lawyering, “instead of taking over and solving problems for your client, you’re increasing clients’ power, putting them in a position to enact the things they want to see. I view it as much more sustainable, much more uplifting, much more effective at making long-term systemic change than traditional client representation.”

The young women of I Am Why would agree. One of them, Jocelyn Mati, said as much in the poem she embedded in her workshop photo collage:

“i AM RESILIENT / 10 years old, waking / up to BANG! BANG! / No not GUNSHOTS. / A black property manager / with a white man in tow / here to reclaim this frame. / i AM WHY / kids and families / won’t ever lose hope!”

I Am Why is encouraging young women to recognize their strengths and to deploy them to change policies and systems that have failed them. Through individual stories, artwork and research, these activists are making their voices heard.