For those who work with the legal needs of juveniles, the repercussions of the current health crisis have been particularly devastating, as the social distancing deemed necessary to control the pandemic has amplified the challenges of the field.

“In this moment lawyers are using every single skill they have,” said BC Law Professor Francine Sherman ’80. “For kids involved in our systems, there are enormous challenges.” Attorneys and the Department of Youth Services in Massachusetts are working hard to address this as well as communicating that the situation is perilous, she stressed.

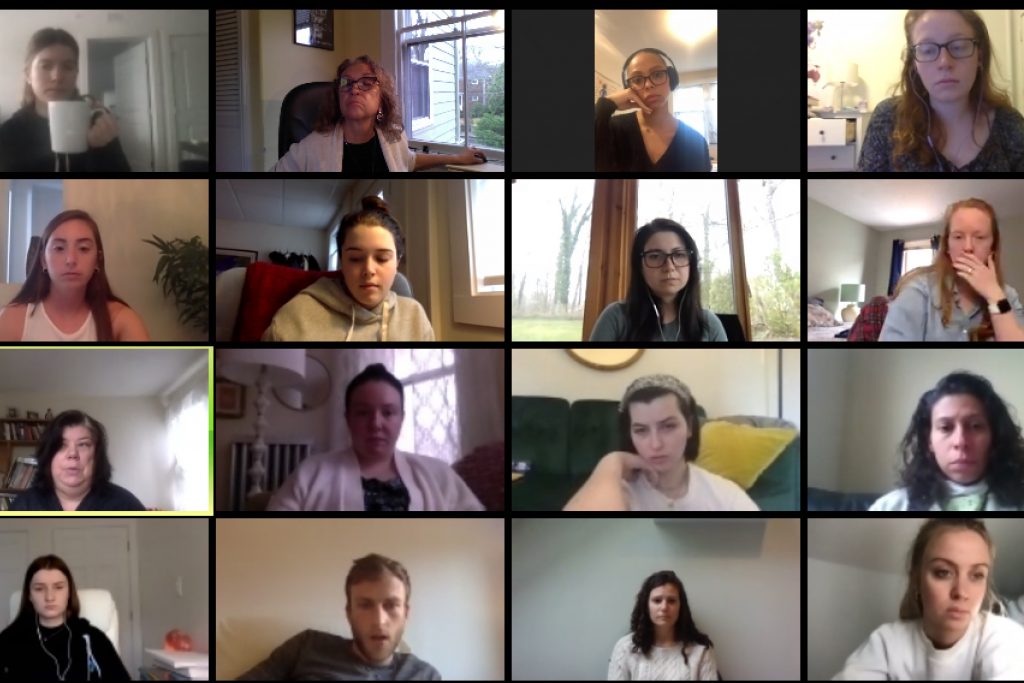

On April 2, Professor Sherman’s Children’s Rights Practice class was an opportunity for state juvenile defense attorneys and advocates to discuss the issues and share responses to this crisis with her 1L students via the cloud-based Zoom app.

The speed with which the crisis descended caught the juvenile system unprepared, her guests shared with the class. When courthouses closed, juveniles who had been arrested ended up being held for days without hearings. “We knew the courts were closed but we didn’t know what that meant,” recalled Mona Igram, attorney in charge at the CPCS Youth Advocacy Division’s Lowell/Lawrence office.

Although some courts have re-opened, with cases consolidated and staffing kept to a minimum, preserving due process has been difficult, and the legal professionals described scrambling to find technological fixes that lessen physical contact without sacrificing constitutionally protected rights. Testimony by video is being reconsidered, they reported, as are phone and online communications. Sentencing is being re-evaluated as well.

Incarceration is especially hazardous right now. “Being in jail or DYS is like being on a cruise ship,” said Holly Smith, attorney in charge of the Committee for Public Counsel Services (CPCS) Youth Advocacy Division in Somerville. She discussed how judges are increasingly considering health and exposure factors, but how advocates need to make sure that such awareness is shared.

Even community sentencing options have been upended. “It’s unreasonable to hold a kid to community service right now,” added Sarah Spofford, a juvenile public defender for the Committee for Public Counsel. “Nobody wants that.” She suggests that lawyers and advocates try to find workarounds, such as remote weekly meetings or educational programs. With schools and programs closed, advocates also have to try to keep their clients in touch with the clinical services often provided by such schools and programs.

In addition, as the skeletal court system currently is only focusing on emergency hearings, functions like home visits by social workers have been indefinitely postponed. “Ninety percent of what we do is not happening,” said Igram.

For the legal professionals who deal with juveniles, this lack of contact presents a special problem. Building trust is vital for juvenile defenders and their teenage clients, but such relationship-building work is complicated without face-to-face communications. “If you think of social distancing as a way of life, we’re the opposite of that,” said Igram. “We’re about proximity.”

“Teenagers are very relational,” added social worker Kelsey Haggett, a social services advocate with the Youth Advocacy Division in Somerville. While options, like Zoom, can help, they can be alienating. In addition, she noted, not everyone has a reliable Wi-Fi connection at home. This places an additional burden on lawyers and other advocates. “Even if we can’t see them face to face, we have to let our clients know we’re still here for them,” she said.

Photo: Faculty, students, and working attorneys discuss the real-life difficulties of advocacy during shutdowns and social distancing.