Carlos Omar Montes arrived in the Bay state from Puerto Rico in the winter of 2007, when he was seventeen years old. He vividly remembers his first day in the US, walking the streets of Framingham in shorts and a tank top as the snow swirled around him.

Montes always wanted to be a barber. He started by grooming horses in Puerto Rico, doing well enough to earn the trust of his family members, thereby gaining human hair-cutting privileges. After moving to the United States, he took advantage of vocational programs and completed the number of hours required to get his barber’s license.

Montes’s plan hit a roadblock when he was incarcerated a few years later for possession of drugs and a firearm. He struggled to get his life on track and ended up spending almost eight years in and out of correctional facilities.

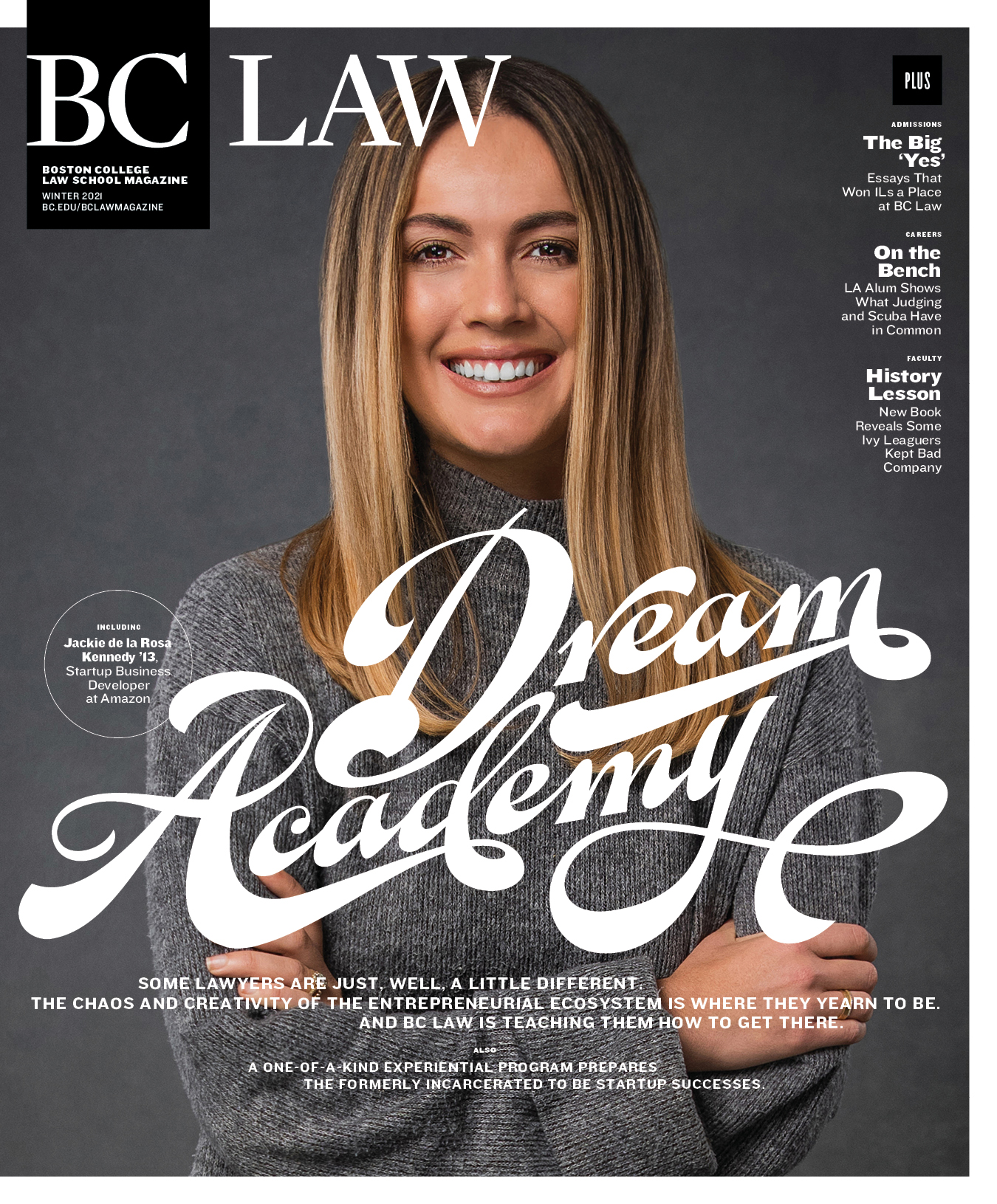

Had it not been for a bold new endeavor at Boston College Law School called Project Entrepreneur, a course taught by BC Law adjunct professor Lawrence Gennari to help citizens returning from incarceration create their own entrepreneurial opportunities, Montes’s future may have been as bleak as that of so many others who have struggled to thrive after imprisonment.

Montes remained active during his years behind bars. He studied law so he could take an active part in his cases. He also taught other inmates how to cut hair. A prison lieutenant approached Montes one day, telling him, “You have all these skills. Why don’t you start teaching people here?” Inspired, Montes began working on plans to start a Corrections Department barber training program. He did research, came up with a proposal, and spent hours thinking deeply about how to integrate his personal skills with his desire to make incarceration more productive for others. Though his training program never became a reality, it set the stage for the kind of creative thinking that being a returning citizen would require.

When Montes was released from Boston’s South Bay House of Correction in 2018, he faced the same obstacles as tens of thousands of other returning citizens. There are over 40,000 collateral consequences of a criminal conviction in the United States. Some are highly visible, such as those that impact voting rights, employment, state benefits, or gun ownership. Others are known only to those who stumble onto a state statute almost by chance. In Alabama, one can be denied employment in the meat and poultry inspection industry. In Illinois, an illegal gambling conviction will bar one from a bingo hall for life. In California, a felony conviction is sufficient to make one ineligible to participate in the Cap-and-Trade Program for greenhouse gas emissions. Massachusetts alone has nearly 800 total consequences governing nearly every facet of life.

“There might be a lot of opportunities, but we as returning citizens don’t see many of them,” Montes says now. “It is a little bit hard to believe or trust.” He spent his first year as a returning citizen living with a friend in Cambridge and used his Master Barber certification to land a job cutting hair. Still, he always imagined working for himself, serving his community in Framingham, showing his old city that he was not defined by who he used to be.

For much of that first year, though, he was confused: “I didn’t know business administration, property management … it was all very hard for me to understand.” Seeking resources to make the most out of his drive to succeed, to grow as a person, and to give back to his community, he turned to the Rehabilitation Department of the Suffolk County District Attorney’s Office and the Boston Returning Citizens Office.

That led Montes to an unexpected place, an April 2019 event in a BC Law classroom listening to other returning citizens pitch their dreams to a group of prominent local businesspeople. Seeing men and women who embodied the ideals he valued most in himself, Montes recognized the worth of the program immediately. Soon, he counted himself among the second cohort of Project Entrepreneur.

The pitch session that Montes witnessed is not the sort of event one would ordinarily expect to see as the culmination of a business law class. Which is precisely why Gennari, who has taught at BC Law since 1996, has made it his mission to redefine what it means to be a business-oriented lawyer.

“Entrepreneurship is the lifeblood of the United States,” says Gennari as he recounts the realizations that led to the creation of Project Entrepreneur, an experiential learning opportunity launched in January of 2019. “For returning citizens, entrepreneurship offers the clearest and brightest path forward.”

Approximately 600,000 people are released from jails and prisons each year. According to the Prison Policy Initiative, the unemployment rate for incarcerated individuals stands at 27 percent. When formerly incarcerated individuals do find work, their wages are up to 20 percent lower than average. Lack of economic stability is a known driver of criminal behavior. In a country with a notoriously high recidivism rate, one of the easiest ways to ensure that people do not end up back in jail and prison is to provide prospects for success once they get out.

Taking stock of this dire situation, Gennari realized that giving returning citizens the tools they needed to start their own businesses would empower them to circumvent some of the residual impacts of having a criminal record. Thinking of what lawyers and law students could do, he began from the basic premise that lawyers “sit in a privileged profession” and are uniquely suited to work with those who are returning from periods of incarceration.

After reaching out to agencies and individuals dedicated to working for and with returning citizens, Gennari realized that programs like the one he was envisioning were few and far between. The closest model, Project Remade, is housed at Stanford University.

Gennari decided to hew closely to Project Remade’s example and designed a course that would integrate law students and community members as guest lecturers and mentors with aspiring entrepreneurs. The pilot class launched during the Spring 2019 semester and welcomed a group of nine law students, each matched with an entrepreneur. During the just-completed Fall 2020 semester, twelve students participated.

For law students, Project Entrepreneur functions similarly to other experiential learning courses. There is a classroom component focusing on advanced corporation law, and a hands-on component that brings the law students and entrepreneurs together for a seminar on business-oriented topics. The first hour of each seminar is taught by law students, the second is often helmed by business leaders from the community.

Gennari notes that for many students, Project Entrepreneur is the first chance to counsel a client and the first time they get to truly hear a client’s story. “I don’t care what degree you’re getting. This is about helping people be their whole selves,” Gennari says. He hopes to strike a balance between opening the eyes of those interested in corporate law or in becoming entrepreneurs themselves and enticing other students to give business a chance, all while serving others through principles of social and restorative justice.

Gennari understands that as with any business venture, success is an uphill battle. The experience helps people develop a skill set, something akin to Montes’s personal mantra of “know what you are capable of.” If the course does not result in the creation of a business, it still leaves returning citizens with a sense of agency, prepared to tackle challenges no matter which avenue they decide to pursue. Ideally, a semester with Project Entrepreneur will leave returning citizens in a better position to respond to the barriers they are facing.

Initially, Carlos Montes planned to start his own barbershop, using some of his income to support the barber training program he envisioned during his time at South Bay. However, through Project Entrepreneur, he realized his business would need something to set it apart in a crowded market. So, he decided to take his craft on the road. A mobile barbershop, complete with old-fashioned touches like a hot lather and warm towels, could replicate the traditional barbershop experience and would enable Montes to meet the demand of prospective customers who were confined to elderly care facilities, retirement communities, and group homes. Plus, the idea of a roving barber wasn’t popular in the US at the time, setting him apart from the competition.

During his semester with Project Entrepreneur, Montes became familiar with the ins and outs of business strategy, marketing, and financing. He also reflected on the fact that English is not his first language, which came into play as he navigated new concepts and prepared to pitch his idea to a roomful of successful businesspeople. But the students he worked with were instrumental in giving him the confidence to keep going. “I learned the importance of having the right people to help me,” says Montes.

Montes’ experience helps explain why Project Entrepreneur has proved such a hit with returning citizens and students.

Stacey Borden, another returned citizen, also attended the Spring 2019 pitch at the recommendation of the Boston Returning Citizens Office. Immediately, she was taken by the idea of bringing formerly incarcerated people into a hands-on academic setting in collaboration with students.

Borden has been developing an organization of her own since 2016. “It’s been in my heart and my mind since I was in that cell ten years ago.” Back then, surrounded by a group of people who taught her how to embrace her strengths and potential, she found her inspiration. “They raised me,” she states simply.“They made me realize I was doing more damage to myself and other women by coming through that revolving door.”

After being released, Borden went back to school. Initially, she set her sights on counseling, earning her bachelor’s degree and working with terminally ill patients during their end-of-life journey. She describes it as the most gratifying experience of her life, one that pushed her to return to school for a second time to get her master’s degree in mental health counseling, thereby becoming a licensed clinician

From there, Borden decided to form her own organization dedicated to reentry, New Beginning Reentry Services. She did not have to dig deep for inspiration, reflecting, “I made a promise to the sisters I left behind.” Borden decided to focus specifically on returning women citizens. “Women have nowhere to lay their head when coming out,” she explained. But her vision extended beyond temporary residential services. “I wanted concrete, measurable things to help women take those first steps.”

“Entrepreneurship is the lifeblood of the United States. For returning citizens, entrepreneurship offers the clearest and brightest path forward.” —Adjunct Professor Lawrence Gennari

And so, after attending that first pitch session at BC Law and hearing about the exciting new program, Borden realized Project Entrepreneur might be the missing piece. With the help of law students and other leaders, she could form a business plan, come up with a sustainable budget, and fill in some of the specifics to ensure her fledging organization would be around for years to come.

For both Montes and Borden, the Project Entrepreneur fulfilled its promise. “Project Entrepreneur really showed me how to understand money, marketing, budgeting, and how to put a plan together and get people to be receptive to it,” says Borden.

So, at the end of the Fall 2019 semester, the BC Law and Greater Boston community again came together to hear the entrepreneurs pitch their business ideas. BC Law students, professors, community businesspeople, and family members gathered to celebrate a semester of growth, and to offer support to assist the entrepreneurs in taking their business ideas to the next level.

When it came time for the pair to make their own pitches, Borden remembers that her ask was simple. “I knew the things I needed to do to obtain the credentials for this type of organization.” She told the crowd of her plan to create a holistic center, called Kimya’s House, after her daughter, that would provide wraparound services to returning women. Reflecting on her own journey, she explained that she knew better than anyone how difficult it was to make it without the help of a larger community of people.

During his pitch, Montes told the crowd about his seventeen-year journey to become a master barber and described how he wanted to use his skills to provide an essential service for those who could no longer make the trip to their barber or hair stylist. While Montes remembers being nervous, he knew, “If I started drowning, they would pick me up.”

This sentiment—that the pitch is so much more than just a business meeting—is intentional. “It isn’t Shark Tank,” Gennari laughs, “it is more like Dolphin Tank.”

After three semesters, Project Entrepreneur has already acted as a cornerstone for the dreams of returning citizens. Though the endeavor will continue to evolve, Gennari is already certain about one thing: “I have found that everyone encountering the class—entrepreneurs, law students, businesspeople—has been remade.”