Kathryn Beaumont Murphy ’08 had several years of work experience, including in higher education, under her belt by the time she enrolled in Boston College Law School. Her dream? To one day work in a university’s general counsel office. Still, as a law student, it wasn’t until she got a placement at the Harvard Office of the General Counsel that she began to see how to make that dream come true.

In the Semester-in-Practice externship she was able to fully appreciate the complexities that comprise a general counsel role. “For example,” Murphy says, “I observed that, even if attorneys had been a real estate partner or a civil litigator in prior positions, they had to be knowledgeable about all areas of the law that impacted Harvard. . . .While each of the attorneys in the office came from a more specialized area of the law, they each did a little of everything. It made me realize that there is a place in the legal profession for a generalist,” she recalls, which was exactly how she saw herself.

Her experiential learning endeavor—which she describes as “likely the most important experience of law school for me in terms of guiding my subsequent career path”—informed her postgrad professional choices; she wanted to acquire a range of legal skills. She started off as a tax associate at a large corporate firm but focused on nonprofits; she spent time as an intellectual property lawyer; she worked in-house for a corporation doing IT and procurement law—which may sound boring, she says—but are essential to universities. And she joined the cybersecurity interest group of one law firm.

All of this—a career blooming from the seeds planted during her externship—led her in 2022 to her current position: Senior General Associate Counsel at Saint Joseph’s University. Not long after arriving, Murphy described it as her destiny: “I’m convinced this job is the reason I went to law school.”

Clinics and externships allow students to gain experience in a field that they are interested in. … But beyond that, for many, it’s the first time they are understanding their role as agents of change, and that revelation can be transformative.

The real power in Murphy’s story is that it’s not at all unique; it is one shared by so many students who navigate through their experiential learning journeys, whether they be in clinics, internships, externships, or summer jobs. In class, professors arm students with an understanding of the law that is nuanced and technically proficient—but students are often hungry for more, for putting those tools to work and for feeling the impact of their work, and it is in experiential learning programs that that hunger is satiated.

“I have seen or heard many students’ ‘aha’ moments in my years of teaching that led them to insights about their own career and professional development,” says Professor Judith McMorrow, who ran the Semester-in-Practice externship program for many years. In some cases, students had their plans affirmed; in others, students realized they weren’t quite on the right track—but the former does not make for a more valuable experience than the latter. One student who was placed in-house with a major sports team realized that the reality of days filled with contract review and licensing agreements wasn’t her passion. “This is a successful placement,” says McMorrow. “It freed her to look outside of sports law for her career.”

She lists other moments she’s witnessed over the years: a student placed in a law firm to do mostly transactional work, who learned, while assisting on a litigation assignment, that she should shift to business litigation; some who simply say that clinic work helps them break out of the structure of traditional classes and feel what it’s really like to be a lawyer; students who are able to engage in their passion for public service—working with children’s rights, immigration, legal services, human rights work, and more. “Many students throughout the years have spoken about the power of being a ‘voice’ for a client… many students have struggled with the ethical issues they are experiencing firsthand—[like] unfair legal systems,” McMorrow says.

For Ali Shafi ’24, who worked with both the Boston College Innocence Program and the Boston College Defenders, clinic work was instrumental not only in his career path, but in how he views the law. “Court for everyone, but especially for the defendant, is a stressful, tiring, frustrating time,” he says of his time assisting indigent clients. “You have to take time off work or find child care, arrive right on time or risk a default judgment, and sit in an intimidating room waiting for the clerk to call your name in a sea of other names.

“There is no joy I have experienced as a young attorney like watching my client thank the judge for the dismissal, walk out of the courtroom, and know that this chapter of their life is over,” he says. “When it is all over and I can see the look of relief on my clients’ faces, that release of tension is palpable.”

Shafi’s time in clinic helped him realize that, while the lessons he’s taught in class are a critical part of legal education, they are only as valuable as they are applicable, and that’s where clinics and experiential learning come in. “Yes, doctrine and case law are fundamental, but so is client communication, passion, curiosity, cultural humility, and a host of other skills that we don’t get to use in a classroom,” he says.

“By getting to know my client so well, I became personally invested in the outcome. … It was pretty powerful to see how I could help someone in such a meaningful way so early in my career.”

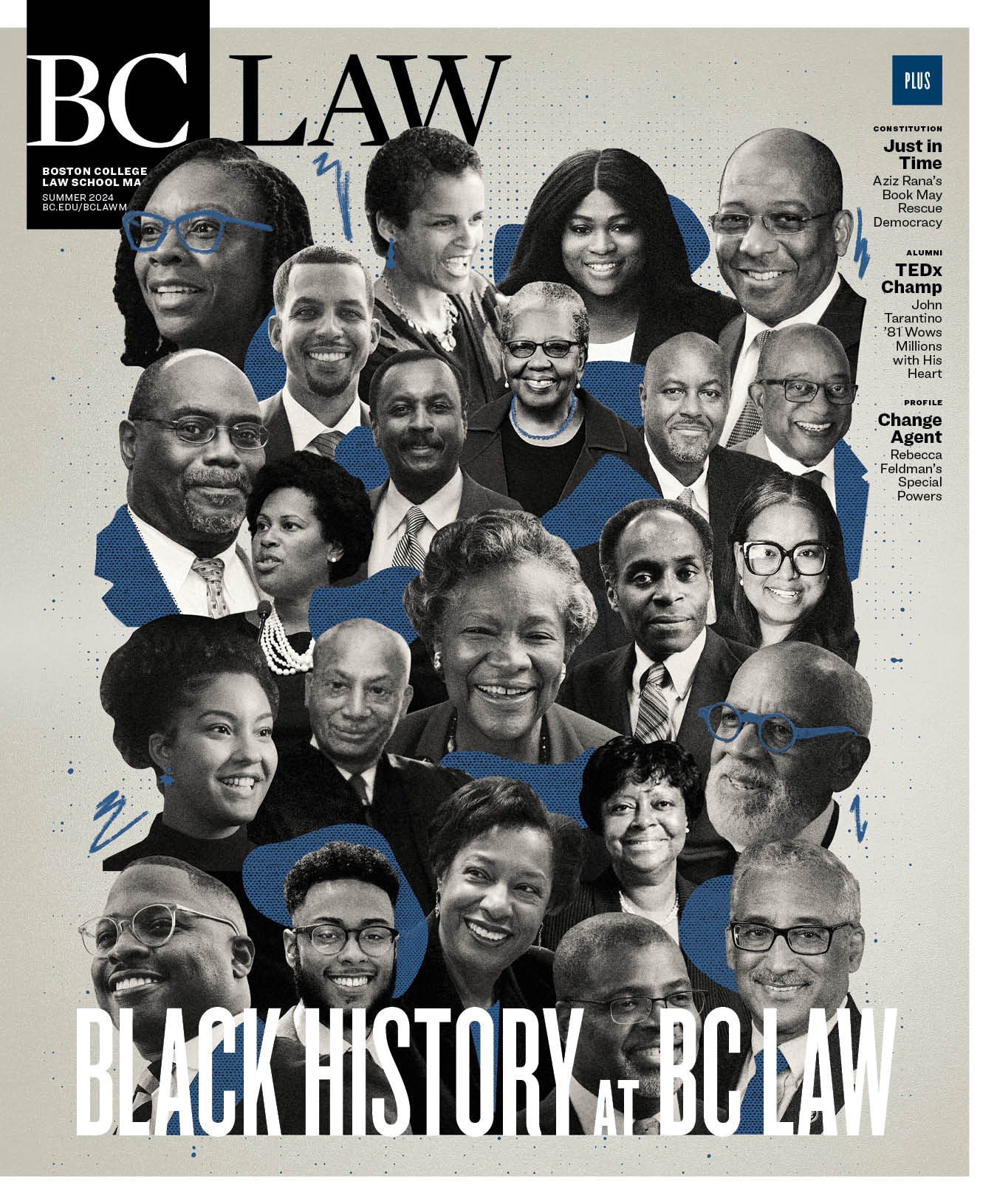

Jaclyn Grodin ’09, above, on her experience as a student in BC Law’s Immigration Clinic

BC Law Clinical Professor and Dean’s Distinguished Scholar Paul R. Tremblay is the director of the Law School’s Community Enterprise Clinic within BC Legal Services LAB. Few better understand the significance of experiential learning. “Law school clinics are, without a doubt, the premier learning opportunities for students who intend to practice law,” he says. “It is unimaginable to me to think of a law student spending three years of study without trying out the experience of actually being a lawyer.”

Tremblay encourages students to consider a clinic in the second year; it helps them begin to contextualize the information they’re learning in class. But more than that, it can serve as an antidote to the disillusionment that sometimes comes after 1L. Clinic work shifts the often grade-centric definition of success and worth that can plague many law students’ journeys. Success is measured differently in clinics, and this more human approach to growth and understanding of the law is what makes students truly understand what the profession looks like after graduation. It stands in stark contrast to that first year of law school; classes jam packed with dense and often dry case law that can feel so far removed from the passions that drive students to choose law school in the first place.

Once a student takes a clinic, “the law becomes ‘real’ in a different way,” Tremblay says. “We have known students feeling like that who then took a clinic, and they realized that the law was far more interesting and fun than it looked like it was going to be.”

Ayesha Ashan ’24 says her time in the BC Civil Rights Clinic, working with the Southern Poverty Law Center and as an extern at the District Court for the District of Columbia, helped her see the nuances of practice as a first-generation law student. It helped her better understand the dynamics at play between judicial positions and litigators. “What is legal isn’t always what is moral or just,” she says. “Clerks and judges can only do what the law allows them to do. But I want to push the boundaries of the law and I want to shift the legal system towards greater equity. This realization affirmed that I’d be more comfortable as an advocate and gave me excitement about my future as a civil rights litigator.”

Critically, one throughline in many of the reflections about clinical and externship work was the realization that lawyering is not about the lawyer: It is about the impact on clients and the world. Students who embrace all that clinics have to offer may go into an experiential learning placement seeking to learn about themselves but what’s often determinative about their future is what they learn about their clients—and the justice system writ large.

“Clinics and externships offer opportunities for discovery and self-reflection,” says Michelle Grossfield, director of the BC Law’s Public Interest and Pro Bono Program. “Universally, students realize their legal advocacy can make a difference to the clients and communities they serve, even as a law student, and that those experiences shape their commitments to public service and pro bono after graduation.”

Law school classes and the intensity of study that marks a legal education can create a sort of tunnel vision; students worship at the altar of GPA’s, of being published in law journals, of landing the most prestigious position for their resume. And while students and graduates certainly reflected on the impact these experiences had on their personal journeys, what really comes through is that clinics and externships are about the people lawyers serve. That’s an invaluable perspective for students to have; a confronting reminder of the injustices of the world and their responsibility as arbiters of the law to do good with our power.

It’s that motivation, says Professor Mary Holper, associate dean for experiential learning and associate clinical professor, that should drive students to do clinic work. “I tell all students that there are so many reasons to do a clinic; first and foremost is to do social justice work on behalf of clients who need your skills,” she says. “Many students wrote about [that] in their admissions essays or were inspired by legal issues they’ve learned about while in law school, but they may not have yet had the opportunity to put into action that desire to do good in the world using your legal skills.”

In a practical sense, clinics and externships allow students to gain experience in a field that they are interested in so that they can hit the ground running once they graduate. But beyond that, for many law students, it’s the first time they are understanding their role as agents of change, and that revelation can be transformative. She’s seen it happen many times, she says.

And it’s an impact that stays with alumni for years after graduation. Jaclyn Grodin graduated in 2009 and she says she still thinks about the time she spent working under Holper in the Immigration Clinic. Her story illustrates the palpable way these experiences expose law students to the injustices of marginalized communities.

During her first semester, Grodin represented a green card holder from Haiti who had lived in the United States since he was a child, and who no longer spoke his native language. When he was arrested in college with a small amount of drugs, he was set to be deported after his prison sentence was completed; once deported, he would have been immediately placed in jail in Haiti. “The jail was one of the most dangerous and violent in the world,” Grodin says. “It’s very possible he would have died.”

For an entire semester, she and Holper visited him in jail where they would talk about his struggles—he was a good kid, she says, who had lived a difficult life. And based on hours and hours of conversations with him, they were able to put together a declaration in support of his cancellation application which detailed not only his life story, but the conditions he would be subjected to in Haiti.

“It was incredible how much effort—listening, research, discussions with Professor Holper, interviews of people my client was friends with and who supported him—went into the application,” she says. “And by getting to know my client so well, I became personally invested in the outcome, meaning that I felt like I had a real chance to quite literally change the course of someone’s life through my legal skills. It was pretty powerful to see how I could help someone in such a meaningful way so early in my career.”

On the same day as their hearing, their application was granted and her client was allowed to stay in the country. Grodin says it was the best moment of her time in clinic, and perhaps of her career to date.