Imagine their conversation.

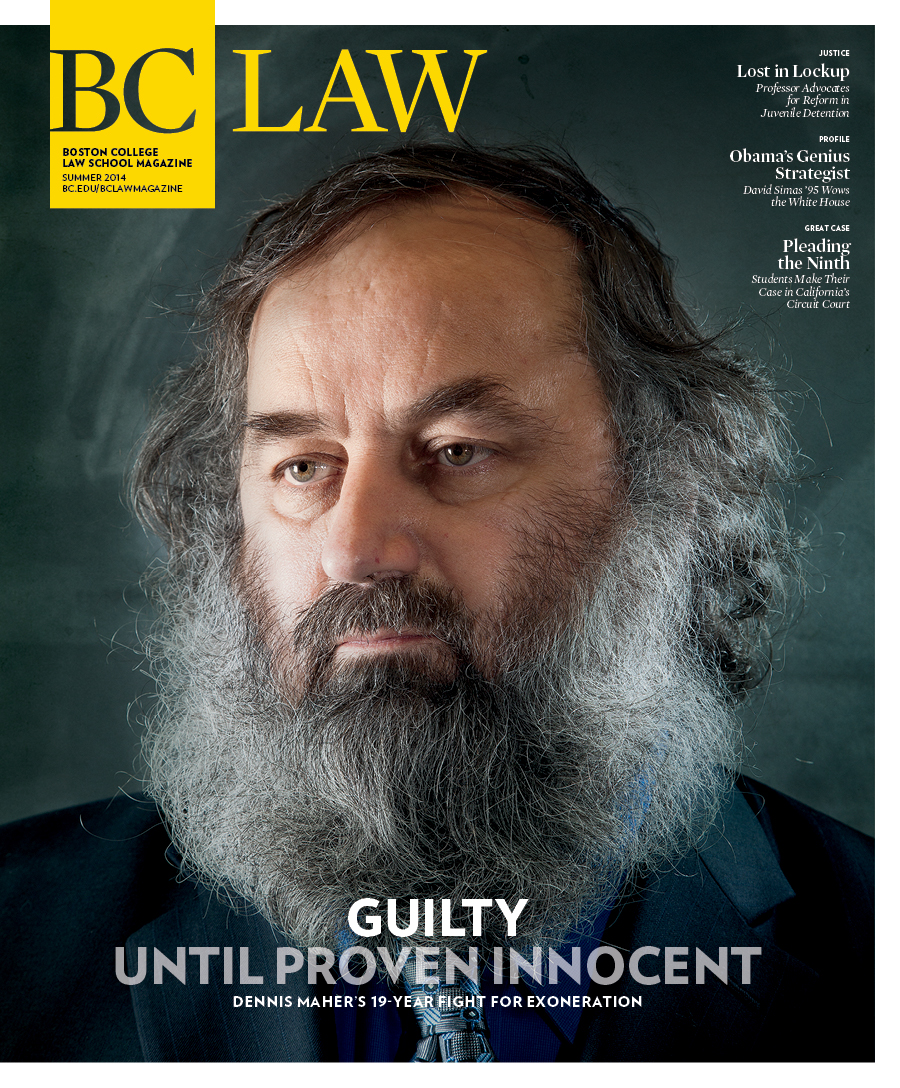

An innocent man imprisoned for more than nineteen years for two rapes and an attempted rape—none of which he committed. His prosecutor, who could never shake the feeling that the convictions were mistakes. The lawyer who proved his innocence and forced the system to set him free.

This is the stuff of serious theater. But these characters are not the creation of an ambitious playwright. They are all quite real. The innocent man is Dennis Maher. The prosecutor is Jay Carney Jr. ’78. The lawyer is Aliza Kaplan. They came together for a panel discussion, “Thirty Years after Wrongful Conviction,” held in a packed lecture hall at the Law School on March 21. The event was sponsored by the Boston College Innocence Project. This is their story.

Lowell, Massachusetts, 1983. Carney had just joined the Massachusetts Middlesex District Attorney’s office. Maher was an enlisted soldier stationed at the Danvers military base and living in Lowell. Kaplan was thirteen and attending middle school in Maplewood, New Jersey. She had just had her bat mitzvah.

On a late, mid-November afternoon, a woman got off at her bus stop after work and started walking home. A man approached, tried to engage her in conversation, then threw her down, threatened to kill her with a knife, and raped her. She went home and called the police. She was examined in a hospital and a sample of semen from her vagina was saved.

The next day, another woman coming home from work got off at the same bus stop. As she walked home, a man came up beside her. Same M.O. She fought him off and was not raped. She, too, called the police. The police had a general description of the assailant, but nothing specific.

On the evening of the attempted rape, Maher was walking to a friend’s house in the area where the attacks had occurred when he was stopped by police. They checked and found that Maher had no prior arrests. They searched him and arrested him for possession of marijuana.

When Maher subsequently realized he was being held on suspicion of rape and attempted rape, he requested a lawyer. The detective in charge, Maher recalls, “leaned down on the desk and said, ‘Just admit to it.’” Maher refused to confess.

The next morning, Maher went to court on the marijuana charge. Using a now-discredited witness identification procedure, they sat Maher on a courtroom bench and had one of the victims come in and look at him. She did not identify him. Maher got six months probation. As he was leaving the courtroom, he was arrested for rape and attempted rape, then released on $10,000 bail.

The police placed the photo they took of Maher from his marijuana arrest into a photo array and showed the victims. The police claimed that both women identified Maher.

A police department detective in Ayer, Massachusetts, a town roughly twenty miles southwest of Lowell, was working on an unsolved rape case in Ayer and took special note of Maher’s arrest. That rape had occurred in August 1983, when a woman staying in an Ayer motel was raped in her room by a man wearing dark clothing and wielding a large knife. She reported the crime to the police, and semen was collected from her in the hospital. She identified Maher from a photo array.

Police seized Maher’s car and searched it. They found army-issued dark clothing and a KA-BAR knife—likely the very same kind of knife that was in dozens of cars from the base. The Ayer detective had a witness who claimed that he had once met Maher at the motel and had seen Maher’s car parked there months earlier.

Carney conducted lineups. Each woman separately ID’d Maher.

Maher was at home with his parents when the police arrested him for the rape and the attempted rape in Lowell. January 5, 1984, was Maher’s last day of freedom. “I was devastated,” Maher says.

His trial lawyer was abysmally incompetent—“It was just horrifying,” Maher says—and he was found guilty of the first rape and of the attempted rape. From his seat at the prosecutor’s table, Carney heard the judge whisper to the clerk Maher’s sentence: ten to fifteen years. Before he announced the sentence, the judge asked Maher if he had anything to say.

“[I was a] twenty-three-year-old soldier,” Maher says. “Of course, I had something to say. I said, ‘Your honor, if you call this justice, I think you and your whole judicial system are a crock of shit.’”

With that, his sentence ballooned to twenty to thirty years.

Maher was then tried and convicted in the Ayer case. Again, Carney was the prosecutor. Maher was sentenced to life in prison. (Carney later learned that the witness who testified that he’d seen Maher at the motel was lying, and that other evidence had either been fabricated or withheld from him.)

Overall, Carney thought the trials were fair—and yet. He did something that he never did again in the five years that he was a prosecutor. He approached the head of the Middlesex County public defenders’ office and said, “I just finished trying this fellow on three charges of sexual assault. I have no affirmative reason to believe that I have the wrong guy, but I do know he had the very worst lawyer I could ever imagine in my life.” Carney urged the defenders’ office to appeal Maher’s case. The defenders’ office assigned the case to an inexperienced lawyer—and the appeals court affirmed all three convictions.

In prison proceedings, Maher, who continued to assert his innocence, was deemed to be a sexually dangerous person and was now, on top of his criminal sentences, civilly sentenced for life to the Massachusetts Treatment Center for sexually dangerous persons at the Bridgewater Correctional Complex. He could be released from the treatment center only if he admitted to the crimes. He refused.

Maher started formally advocating for a new trial. All his motions were being entertained by the sentencing judge. The judge denied every one of them without a hearing.

Then, in 1993, Maher saw Phil Donahue, the talk show host, on TV. Donahue’s guest was Barry Scheck, co-founder of the then-new Innocence Project of Yeshiva University’s Cardozo School of Law, which was using DNA evidence to exonerate wrongly convicted prisoners. Maher wrote to the project for help. Innocence Project interns reviewed his case and requested physical evidence from Middlesex County. Officials claimed that the evidence was lost. In 1997, Barry Scheck filed for DNA testing. His motion was denied without a hearing.

“So now at this time, I’m devastated,” Maher says. “All my hopes and dreams are resting on DNA. I made peace with myself that I was going to die in prison as an innocent man.”

Two years later, Maher was contacted for an interview by Boston Globe reporter John Ellement. At the interview, Maher asked Ellement: “Who sent you? How did you get here?”

Jay Carney.

Ellement wanted to write a story about a wrongful conviction, and he reached out to Carney, at this point a prominent criminal defense lawyer, for help. Carney told him about Maher. “If you can show that Dennis is innocent,” Carney told Ellement, “you’ll get the Pulitzer Prize.” Ellement, however, wound up writing about another man.

Carney became aware of Maher’s repeated attempts to have DNA testing. He urged the head of the appeals bureau in Middlesex County DA’s office to allow the tests—to no avail.

Meanwhile, Aliza Kaplan was a young associate with the Boston law firm Testa Hurwitz & Thibeault. Her very first week of work, she landed a plum assignment. The law firm was starting up a New England Innocence Project in their offices, and they wanted her on it.

The Innocence Project in New York shipped all its New England cases to Testa Hurwitz. One was the Kenny Waters case, memorialized in the movie Conviction starring Hillary Swank. In that case, the evidence that would eventually exonerate Waters was found in boxes in the basement of the Middlesex County Courthouse.

Another case was Maher’s. Kaplan and her law student interns saw that Barry Scheck himself had filed a motion for DNA testing on Maher’s behalf. “Let’s go visit this guy,” Kaplan told one of her interns, a law student named Karin Burns.

They went to the Massachusetts treatment center, not knowing what to expect, not really sure that their guy was innocent. Kaplan recalls that a big door opened and the guard on the other side said, “You here to see Maher?” She told him they were from the Innocence Project. The year was now 2000. He said, “It’s about time you got here.”

Maher told Kaplan his story, and about John Ellement and Jay Carney. Kaplan reached out to Carney. He described his qualms, and even offered to help.

If there was going to be DNA testing, Kaplan and Burns had to find the evidence. For months, they filed motions, made phone calls, and got nowhere. Then Burns became friendly with one of the courthouse clerks. She reminded him of the Kenny Waters case, and asked him to look in the courthouse basement. He did. Down there were two big boxes from the Lowell case, labeled with Maher’s name.

Kaplan called the DA and told him, the boxes are there, I’m about to file this motion, either respond in court or fess up. They fessed up. Kaplan and an assistant DA went to the state crime lab to see if the victim’s clothes inside the boxes harbored DNA evidence. They did. There was semen on the underpants of the rape victim from Lowell.

The evidence was sent to a lab in California to be tested by a Dr. Blake, then the country’s foremost expert in DNA testing. Maher underwent a blood test. On Christmas Eve of 2002, Kaplan got a call.

“We have the results,” Dr. Blake said. “It’s not Dennis.”

Kaplan told the DA: You got the wrong guy. But the DA said: What about Ayer?

Then-Middlesex District Attorney Martha Coakley called Kaplan and offered to make a deal in the Ayer case. “Aliza,” Maher recalls, “had some choice words for Martha Coakley.” Two weeks later, evidence containing DNA from the Ayer case suddenly appeared on Coakley’s desk. The evidence was tested. Again, not Dennis. Kaplan called Maher and said, “When do you want to go home?”

Maher’s last strip search was April 3, 2003. Despite everything, he was transported to the Cambridge courthouse in chains. The judge signed the papers and Maher was free. He was reunited with his parents, then with the rest of his family and friends. Then—the media throng. Kaplan shooed the reporters off to a scheduled press conference at her law firm.

Maher remembers: “As I’m leaving, the senior court officer comes over and says, ‘Jay Carney would like to speak with you.’”

Carney first heard of Maher’s exoneration from Barry Scheck. “It hit me like a punch in the stomach,” Carney said. “I sat in the courtroom when Dennis was being released.” Afterward, “I went up to the chief court officer and said, could you ask Mr. Maher if he would meet with me? And I went behind a set of double doors. And suddenly I see Dennis coming toward me.

“I reintroduced myself to Dennis and I asked him if he could forgive me. I said I would understand if you can’t. But I just want to tell you how very sorry I am that I played this role in this case,” Carney remembers. “The single most profound moment in my career then happened. Dennis said, ‘I’ve already forgiven you.’ And we hugged.”

“I don’t know what would have happened if he had said, ‘Jay, I’m sorry. I can’t.’ But I do know that it showed me that after love, the most powerful emotion that we have is to forgive. Whenever I’m in a situation where I don’t want to forgive someone who’s done something, I think of Dennis. And he taught me the power of that, and I’ll always be grateful. The most amazing person I’ve ever, ever encountered in my life.”

As the men parted and Maher got on the elevator, Carney realized that the Globe reporter John Ellement was standing nearby. Carney whispered to him, “There goes your Pulitzer Prize.”

Today: Aliza Kaplan is a law professor at Lewis & Clark Law School where she teaches legal skills, Wrongful Convictions, and public interest lawyering. She recently co-founded the Oregon Innocence Project.

Jay Carney is a highly regarded criminal defense lawyer in Boston. He recently represented mobster James “Whitey” Bulger at his trial.

Maher works in waste management, a job he has held since a month after his release. He lives with his wife Melissa in a house they own in Tewksbury, Massachusetts. They have two children, a boy named Joshua, and a girl named Aliza—for the lawyer who gave him back the rest of his life.

To view the Innocence Project panel discussion, go to bc.edu/lawmagvideos.

Innocence by the Numbers

The leading causes of wrongful convictions are eyewitness misidentification, poor forensic science, false confessions and incriminating statements, and informant testimony. No one knows for sure how big the problem is. According to the University of Michigan Law School’s National Registry of Exonerations, 873 people were exonerated from January 1989 through 2012. Of these:

37% were cleared with DNA evidence. 63% were cleared without DNA evidence. 93% were men. 50% were African-American; 38% were white; 11% were Latino; 2% were Native American or Asian-American. 87% were convicted at jury trials. 50% were in prison for at least ten years.

The national Innocence Project reports that eighteen of the people exonerated through DNA testing served time on death row.

Jeri Zeder is a longtime contributor to BC Law Magazine. She can be reached at jzbclaw@rede.zpato.net.