When I declined my former law firm’s generous offer to return to them after completing my LLM degree at Harvard Law School, my boss said, “Someday you will regret this. Vietnam is your turf. America is brutal.” He may have been right both about me and about US legal practice, but having been a fighter for almost all my life and career, I am determined to start my legal career from scratch in America.

In Vietnam, a deeply Confucius-influenced society, people tend to view women as subordinate to men and therefore predisposed to listen and obey rather than to make decisions and lead. Brought up in a traditional Vietnamese family, I was taught that a good woman should never argue or openly express her opinion. Against my dear parents’ wishes, I turned out to be the antithesis of that traditional model: I am opinionated, able to stand up and speak without fear of being judged, and I love intellectual challenges.

My decision to become a lawyer derives from my belief that the law has significant power to change both society and individual lives through promoting economic development. Growing up under a communist regime in one of the most war-ravaged countries since World War II, I saw how the enactment and effective enforcement of good laws helped millions of people get out of poverty. On the other hand, I also experienced how bad laws and weak legal enforcement restricted economic activities and drove a nation with great potential backward.

It is difficult to practice as a lawyer in Vietnam. Many have been beaten, slandered, and arrested for defending clients whose interests run contrary to those of the powerful people running the country. Thriving as a female lawyer, however, is significantly more challenging. The only way to overcome the social prejudice against me as a female attorney was to deliver excellent legal services. I managed to become a corporate lawyer at a top-tier international law firm in Vietnam while also being the first in my generation in Vietnam to gain admission to Harvard Law School’s LLM program. Fortunately, I did not have to face the abuse that my parents so feared. I also joined a small handful of female lawyers who advised the government on important laws designed to foster both direct foreign investment and the private sector in Vietnam, the two major pillars of Vietnam’s economy.

After several years of legal practice in Vietnam, I experienced significant constraints in the practice of law in my country. With rampant corruption and no impartial judicial system, there is always an illegal way for people to escape justice. I will never forget, for example, the time when the court denied our right to defend our client because the hostile judges publicly sided with the other party, a powerful state-owned company with strong government connections.

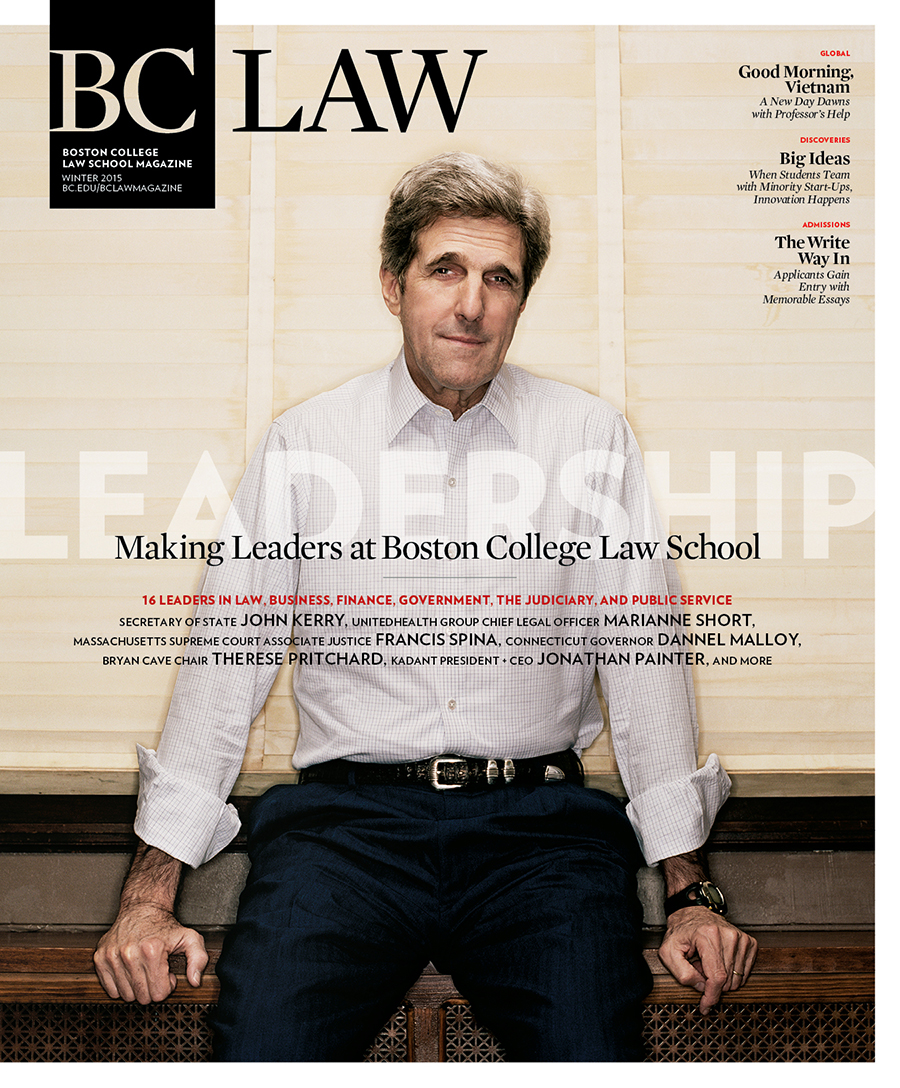

My emigration to the United States gave me the opportunity to develop my career in the most sophisticated legal market in the world. Noting the large gap in terms of professional knowledge, skills, and connections between foreign attorneys and the American JD-trained attorneys, however, I decided to acquire the same educational attainments as American lawyers.

My success as a lawyer in America will help me achieve my life’s goal of improving the lives of many disadvantaged people by using the law to foster economic growth. It will also enable me to set a good example for the young women in the Vietnamese community so that, regardless of their background, there is no limit to what they can achieve and where they can go if they dare to follow their dreams.