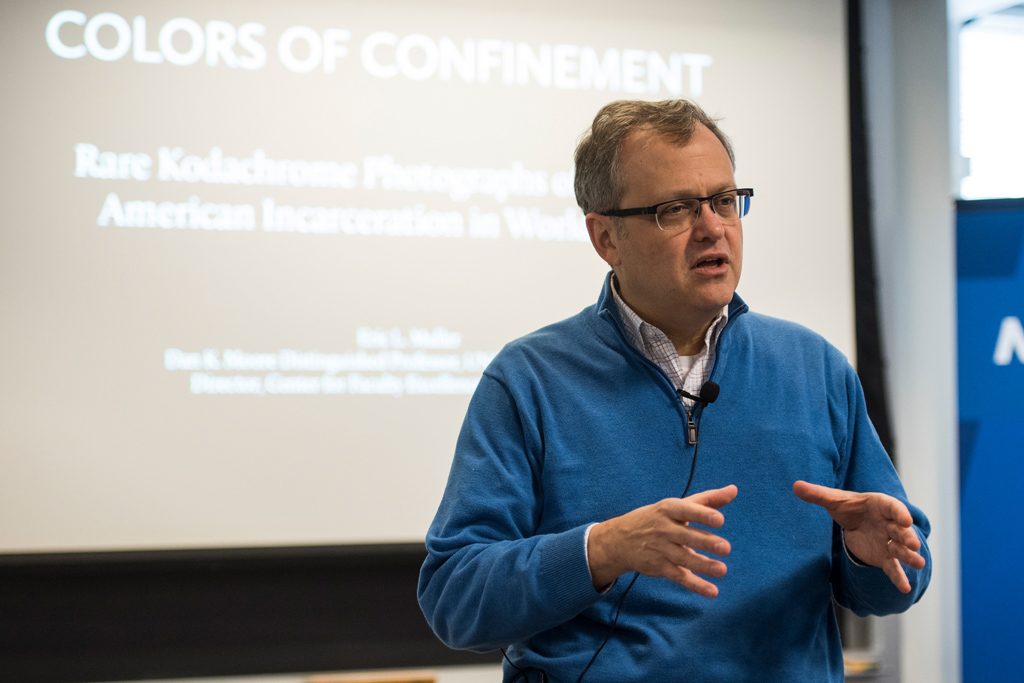

Professor Eric Muller, of University of North Carolina Law School, sat at one end of the seminar table in the Daniel R. Coquillette Rare Book Room at Boston College Law School and talked about the lawyers who helped run internment camps for Japanese-Americans during World War II.

Author of three books on the wartime status of Japanese Americans, Muller quickly summarized his article on the internment camp lawyers, forthcoming in the Law and History Review, and then spent the better part of an hour taking questions from attendees of the Legal History Roundtable, a program that has brought some 60 distinguished lawyers, historians, and lawyer-historians to the BC Law campus.

Muller pointed out that scholarship on the internment camps, which began with the rise of ethnic studies in the 1960s, has tended to view them as having been ruled with an iron hand by a “monolithic top-down bureaucracy.” From his review of weekly reports that “project lawyers” from the Heart Mountain Camp in Wyoming, among other internment facilities, sent to the home office in Washington, he has concluded that, on the contrary, the camps, “were a model of reciprocal accommodation.”

While Japanese-Americans were relocated on orders of an army general who held “biological racist views,” Muller said, the War Relocation Authority camps were staffed by civilians, of whom many had formerly worked in New Deal programs that put a central value on cooperative decision-making. Thus, the project lawyers at Heart Mountain often ended up helping internees bend WRA rules—on matters like self-governance and controversial decisions by an inmate-run judiciary body—by advocating for them with higher-ups in Washington.

Muller spent much of the hour-long session talking about the contradiction between the “deeply unjust and illegal” treatment of Japanese-Americans and the fact that camp authorities managed, at the margins, to provide “a kind of dignity for these people.” The accommodation broke down, he admitted, when inmates threatened the smooth running of camps—by being absent without authorization, for instance. But the lawyers and their bosses, the camp directors, were “much more interested in what was going to work and what would sustain a level of peace than [orders] coming down from Washington,” said Muller. In addition, staff members at the camps saw themselves as a humane and enlightened alternative to military oversight of the camps. They thought, as Muller put it, that they were “making the best of a bad situation.”

The story might have turned out worse if the war had proceeded differently, Muller conceded. “What if we had lost at Midway? What if there had been more stories of atrocities against US servicemen? Would the camps have stayed the way they were?” he asked.

Muller said he doubted it.

BC’s Legal History Roundtable guests have included Pulitzer Prize-winner Annette Gordon-Reed and Bancroft Prize-winner Tomiko Brown-Nagin, both of Harvard Law School; Pulitzer Prize-winner Jack Rakove, of Stanford University; Bancroft Prize-winner John Fabian Witt of Yale Law School; and the Hon. Margaret Marshall, of the Supreme Judicial Court of Massachusetts.

BC Law Professor Mary Bilder, herself a Bancroft Prize-winner for Madison’s Hand, is a co-convener of the roundtable events.

Photograph by Christopher Soldt, MTS, BC