It was June of 1992, the second night of the holiday Eid al-Adha, when Elvedin Pasic, just fourteen, saw Serb forces attack his small Muslim village of Hrvaćani, Bosnia.

The community scattered; Pasic escaped through a window with his mother. Elderly neighbors, unable to flee, were shot or burned alive. Hrvaćani was reduced to ruins. Surviving villagers went into hiding, but in November were captured by Serb forces. Intent on massacre, soldiers forced their captives to form three lines and lie down in the mud. Pasic lay down between his father and his uncle. The women and children were ordered to get up and leave. Pasic’s father and uncle insisted that Pasic join them. Pasic never saw his father and uncle again.

Twenty years later, on July 9, 2012, Pasic, in tears, told the world his story as the first witness in the last trial of the International Criminal Tribunal for the Former Yugoslavia (ICTY)—the trial of Ratko Mladić. Pasic’s testimony set up the prosecution’s case that Mladić sought to destroy Bosnia’s non-Serbian peoples through murder, mass expulsions, and atrocities against civilians.

Leading the prosecution was Dermot Groome ’85.

In the rarefied world of international criminal justice, Groome is renowned. Besides serving as senior prosecutor in eight trials at the ICTY, including the trial of Slobodan Milošević, Groome literally wrote the book on investigating human rights abuses. With his masterful ability to coordinate the vast, complex mix of people, evidence, and documents involved in war crimes prosecutions, Groome has set professional standards. He made significant contributions to the development of international law. And his admonitions about the future of international criminal justice are warnings for us all.

The ICTY was created by the UN Security Council and operated in The Hague from 1993 to 2017. The first war crimes tribunal since Nuremburg, its purpose was to bring to justice those who had committed genocide, crimes against humanity, and war crimes during the 1992-1995 Bosnian War. The descent into war began with the death of Yugoslav’s strongman president Josip Tito in 1980. As the economy declined, opportunistic politicians began sowing ethnic discord among the Muslims, Serbs, and Croats of Bosnia-Herzegovina. Eventually, the coalition government collapsed. Croatia, Slovenia, and Serbia became independent nations. In April 1992, seeking domination, Serbian forces bombed Sarajevo and began the brutal “ethnic cleansing” of non-Serbs. In Europe’s worst mass murder since World War II, nearly 8,000 Muslim men and boys were massacred in Srebrenica; another 20,000 civilians were expelled. By war’s end, some 130,000 people had been killed and two- to four million displaced.

In the rarefied world of international criminal justice, Groome is renowned. With his masterful ability to coordinate the vast, complex mix of people, evidence, and documents involved in war crimes prosecutions, he has set professional standards.

Mladić, the commander of the Serbian army, was indicted by the tribunal in 1995, but remained a fugitive until his arrest in 2011. A year later, he was put on trial for crimes committed in Sarajevo, Srebrenica, and fifteen other municipalities. He was charged with eleven counts: four of violations of the laws of war (murder, terrorism, attacks on civilians, the taking of hostages), five of crimes against humanity (murder, persecution, extermination, deportation, forcible transfer), and two of genocide. To prove genocide, the prosecution had to show beyond a reasonable doubt that the defendant intended to destroy in whole or in part a particular ethnic group. Mladić’s defense team argued that he was innocent, that he had never participated in, nor ordered, any crimes.

In an interesting legal wrinkle, the statute governing the ICTY did not explicitly provide for a way to hold accountable heads of state (like Milošević) or senior political and military leaders (like Mladić)—people who didn’t actually pull the trigger, but were culpable at a strategic level. During the Nuremberg trials, prosecutors used the “common purpose” doctrine against multiple perpetrators who cooperated and coordinated with each other to commit atrocity crimes. Groome reconceptualized the common-purpose doctrine to apply to high-level perpetrators, and persuaded the ICTY that the idea was implicit in the court’s guiding statute. The concept became known as “joint criminal enterprise,” and is now a core legal theory of international criminal law.

One of the prosecution’s witnesses was Saliha Osmanović of Srebrenica, whose two sons and husband were killed in the war. As a Muslim in fear for her life, she had fled to a refugee camp in July of 1995. Her testimony was intended to support the “ethnic cleansing” and “forcible transfer” counts against Mladić. On cross-examination, the defense tried to shake her testimony using film footage from Srebrenica:

Defense attorney: “The demeanor of General Mladić, is it similar to or different from the demeanor of General Mladić during the encounter that you remember with him?”

Osmanović: “I don’t know. He seems to be nicer on the video when he says the children should go on ahead.”

Defense attorney: “Madam, you mentioned that there was water and chocolates being handed out. Was there also bread being handed out by the VRS soldiers?”

Osmanović: “Yes, certainly. They must have fed them and then killed them! It was a show for the camera. They should have just let everyone go. It was hell. But I saw Mladić, believe me. I know that. I am not a fool! I lost two sons. I lost my husband. I don’t need these stories anymore.”

The testimony of Saliha Osmanović hints at the meaning of bringing traumatized victims of war crimes into court. Camille Bibles, now a federal magistrate judge for the US District Court in Arizona, was a prosecutor for both the Mladić and the Milošević trials. She recalls an illiterate farmer—a massacre survivor—telling her, “‘Milošević was everywhere. He had his statues, his face was everywhere, and here I am, I’m going into a courtroom and I am going to hold my own against that man.’”

Rape was a weapon of war used by the Serbs against Muslim women; by some estimates, 25,000 to 50,000 women were held captive and raped repeatedly. Rape victims’ testimony was necessary to prove atrocities, and helping women to come forward and appear in court was especially challenging.

“I can think of several instances where women who had been victimized by a sexual offense, who had suffered enormously—Dermot would do everything from having their therapist present to whatever they needed for their support,” Bibles says. “There were women who came out from testifying and facing their abuser and felt empowered as a result of that testimony. That is the mark of a remarkable attorney.”

Victims, of course, were not the only witnesses. Perpetrators were witnesses, too, including “hardened and cynical insiders, like the ex-paramilitary soldiers whose comrades-in-arms had committed terrible crimes in Croatia and Bosnia,” says Travis Farr, an ICTY prosecutor who is now at the Extraordinary Chambers in the Courts of Cambodia. “Dermot dealt effectively with them all.”

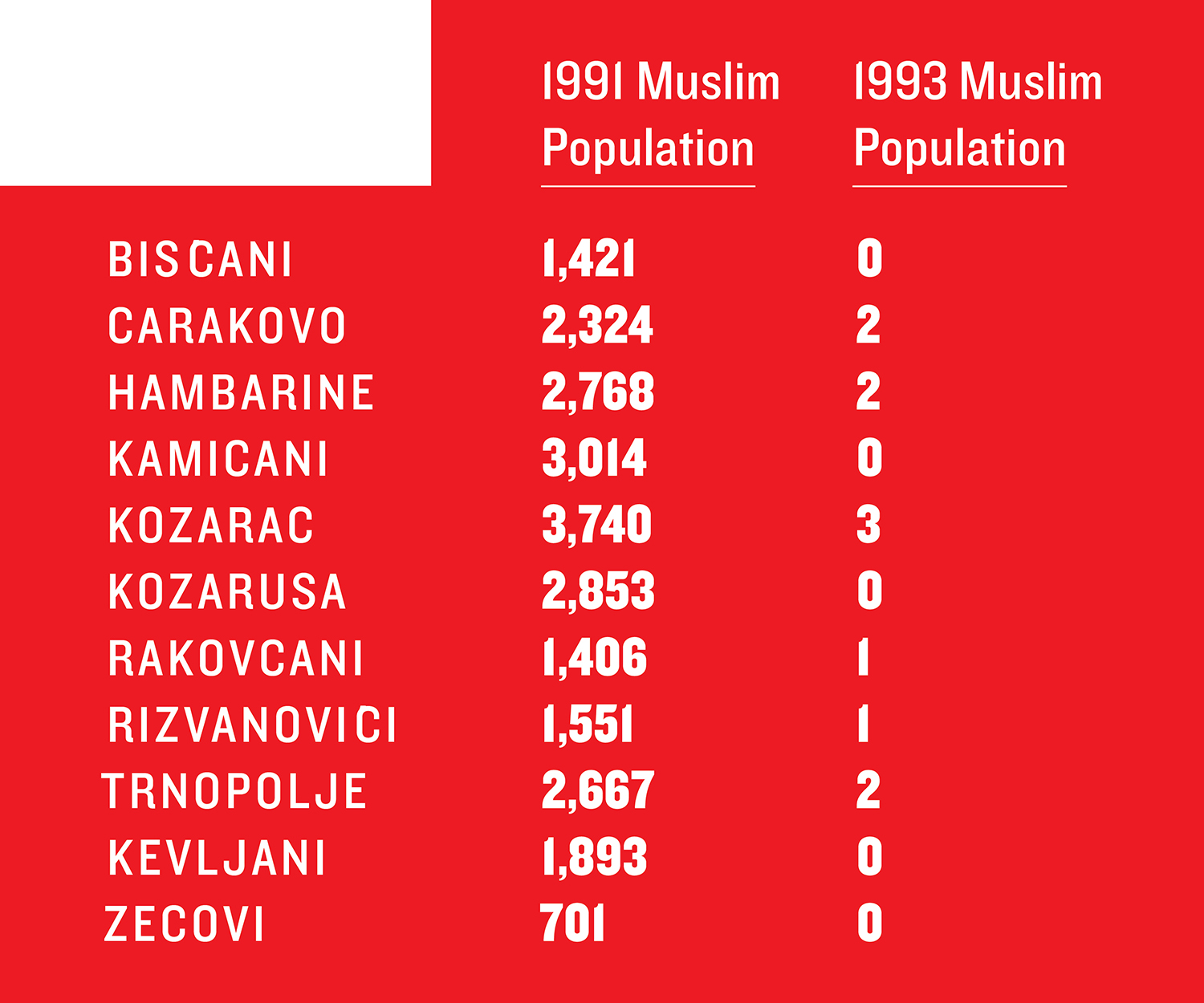

This chart, developed by the prosecutors and shared with Frontline for the documentary The Trial of Ratko Mladić, shows the population census before and after Mladić’s troops stormed the villages surrounding the city of Prijedor, Bosnia:

There were whispers that a mass grave existed in Prijedor, but no one would say where it was. Then, in September 2013, the prosecution learned its location: the Tomašica Iron Mine.

In November, more than 200 days into the trial, Groome traveled to Tomašica with a team of investigators to observe the excavation. In the Frontline documentary, Groome stands amid a bleak landscape, his hands in his pockets, hunched against the wind, as bulldozers groan over the ground. Pathologists will try to determine the identity and cause of death for each and every body that’s exhumed. Evidence of point-blank range gunshot wounds to the heads and bodies of hundreds of men, women, and children buried in the mine will join with evidence of the thousands of other people in the area who were murdered, starved, abused, and burned out of their homes and mosques. The prosecution will argue that this destruction was conducted by Mladić and constitutes genocide.

Groome was still in law school when he served as an intern at the district attorney’s office of Middlesex County, Massachusetts. “I actually remember vomiting the first time I saw crime scene photos,” he says. Long experience has given him the ability to stand amid the stench and horror of places like the Tomašica Mine—which, he told the Frontline filmmakers, was “beyond anything I’ve ever dealt with”—but he has not been hardened.

“Obviously, my work has required me to deal with people who have suffered greatly, and it has exposed me to some of the worst examples of what people can do to each other,” Groome says. “One of the ways that I changed: I think I learned that, in each of these crimes, no matter how great the evil embodied in the crime, there are always acts of great courage, goodness, and self-sacrifice that counterbalance and sometimes even outweigh the evil.” He cites as an example a woman who was burned alive with sixty other women and children. She escaped and, naked and flayed, ran from door to door in her village warning others to flee. Then, she returned to the perpetrators and begged them to shoot her. When they refused, she fled and survived and testified at trial.

“When I did this work,” Groome says, “I was always vigilant to see these great acts of goodness in every crime that I have dealt with, and I can say that, in every crime I’ve dealt with, I’ve found such goodness.” Groome’s Catholic faith has also centered him. “I don’t know why such awful things happen or whether God allows them to happen, but I do know that as awful as these crimes are, and as tremendous as the suffering is, it is in these crimes that a sense of God has been most proximate in my life.”

It took eight months to gather and analyze all the forensic evidence from Tomašica and collect witness statements. Groome’s team had to persuade the court to re-open the prosecution’s case-in-chief and allow evidence from the mine to be entered at trial. If allowed, the ruling would be a significant setback for the defense.

On October 23, 2014, the tribunal ruled for the prosecution. The forensics from the mine, the court said, was “fresh evidence,” “relevant to the charges in the municipalities’ component of the case and of probative value.”

Tomašica underscores the enormity of the Mladić case. The trial lasted four-and-a-half years, with 530 trial days. Some sixty people worked on Groome’s team, including more than twenty lawyers and dozens of investigators, analysts, and translators. (More than 100 interns rotated through the case, some from BC Law through a program founded by former ICTY prosecutor Phillip L. Weiner ’80.) Eight million pages of documents were combed through, with anything exculpatory turned over to the defense. Ten thousand exhibits were entered into evidence. Hundreds of motions and responses were filed. Six hundred witnesses testified. It took eleven months for the judges to reach a verdict. The written judgment is three thousand pages long, fills five volumes, and contains nineteen thousand footnotes.

“The world has become complacent to atrocity crimes. …Our once courageous Security Council that once boldly used its Chapter 7 authority to safeguard peace and security, to create the ICTY and ICTR [the Rwandan tribunal], has proved dysfunctional and impotent.”

It wasn’t unusual for Groome to be at his desk by 5:00 a.m. and to work deep into the night and on weekends, breaking only for dinner with his family. “You would expect someone working that kind of schedule would be a little grouchy,” says Bibles. “He was not. He was a positive force.”

Facing daunting situations by sizing them up and simply taking care of them is a theme of Groome’s career. In 1989, when he needed a break from his job prosecuting violent crimes at the Manhattan DA’s office, he took a sabbatical in Jamaica, where he founded a nonprofit to rebuild homes destroyed by hurricane. While there, he met his wife. A year after returning to the DA’s office, he left for good to live in Jamaica, where he directed the children’s home where his wife worked, and got involved in issues of policing and human rights.

Six years later, Groome relocated to Cambodia, where he served as legal advisor to various human rights NGOs, and to the Minister of Justice and the courts of Cambodia. He gave human rights trainings to judges, prosecutors, police, and government officials. It was in Cambodia that Groome saw the need for a practical manual detailing how to investigate and document human rights abuses. First published in 2001 with a second edition in 2011, The Handbook of Human Rights Investigation has been translated into Serbo-Croatian and Arabic, and is assigned in university and law school courses. War crimes tribunals typically bring together practitioners from many cultures and diverse legal traditions; the manual gives them all a way to work together effectively. Professor Dr. Guénaël Mettraux, a judge of the Kosovo Specialist Chambers who was a legal advisor to an ICTY judge during the Milošević case, calls the Handbook “one of, if not the, most useful practical manuals” for human rights investigations.

Two-and-a-half years into the Mladić trial, Groome left the tribunal to attend to personal family issues in the United States. At that point, he had led the prosecution team during the prosecution’s case, and much of the defense’s case. His successor was inheriting a truly tight team. “There was a real sense of taking care of each other and recognizing the difficulties and the stresses involved in the impacts on families that these trials had, and trying to mitigate that by supporting each other,” says Groome, who is now a law professor at Pennsylvania State University’s Dickinson Law School.

Groome calls out the Serbian team members for special recognition. “They devoted a large portion of their careers to come to the ICTY to help us understand how these crimes occurred,” he says. “They did it out of a real sense of love and patriotism for their country because they really believed that the truth had to come out for Serbia to move forward.” And it wasn’t just team members; Serbian witnesses came forward, too. “We would not have had the success we had without the commitments and service of the Serbs,” he says.

The tribunal heard closing arguments in December of 2016. On November 22, 2017, it rendered its judgment.

On the four counts of violations of the laws of war: guilty.

On the five counts of crimes against humanity: guilty.

On count 2, genocide: guilty.

But on count 1, genocide: not guilty. The court said it “was not satisfied that the only reasonable inference was that the physical perpetrators possessed the required intent to destroy a substantial part of the protected group of Bosnian Muslims” in the municipalities covered in count 1. One of those municipalities was Prijedor. The court did, however, find that Mladić was guilty of ethnic cleansing there.

Mladić was sentenced to life imprisonment.

A month later, the ICTY closed its doors for good. During its operation, a number of other temporary war crimes tribunals were also running (see sidebar). A permanent tribunal—the International Criminal Court in The Hague—was established in 2002. The US helped draft the court’s rules and procedures, but has never ratified it and has refused to become a state party. In April 2019, the Trump administration revoked the entry visa of ICC prosecutor Fatou Bensouda, apparently because she had called for an investigation into war crimes in Afghanistan that could implicate US troops. In protest, none other than Nuremberg prosecutor Ben Ferencz, age 99, lamented that the US “is the very country that built the house called modern international criminal law” in an op-ed for The Hill.

“The world has become complacent to atrocity crimes,” Groome acknowledges. War crimes have been committed in Syria, in Sri Lanka, Myanmar, and against the Yazidi women of Iraq, and the world has done nothing. The UN Security Council has the authority to refer a country for investigation and prosecution in the ICC, even if the country is not a party to the court. But, says Groome, “our once courageous Security Council that once boldly used its Chapter 7 authority to safeguard peace and security, to create the ICTY and ICTR [the Rwandan tribunal], has proved dysfunctional and impotent.”

International tribunals do great things. They bring to account perpetrators of war crimes. They offer credible forums for victims to tell the truth to their tormentors and the world. They document and preserve the historical record.

And yet.

“People holding deeply rooted animosities are not going to abandon them when confronted by a well-reasoned, thoroughly referenced judgment citing what happened,” Groome says. A tribunal can set the table for reconciliation. But only the people can pull up a chair.

(Henry Singer, director of The Trial of Ratko Mladić, attended a screening of the film at Boston College on February 20. Also in attendance were Dermot Groome, via Zoom, and Professors Steven Koh, Daniel Kanstroom, and Allan Ryan Jr. Read the story in BC’s The Gavel.