Landon Stinson ’19 went to law school interested in too many things. Or so it seemed. An economics major in college, he was also drawn to technology. And physics. And engineering. He was getting advice that maybe all his interests would come together if he became a patent lawyer. But he soon learned that it was the inventions themselves, not the body of patent law, that fascinated him. Stinson didn’t know it yet, but he was about to join the ranks of lawyers who become founders of innovative startups.

It turns out, Boston College Law School was just the place for a student like Stinson. In addition to its suite of offerings—courses like Project Entrepreneur, clinics, student-run societies, and globally influential initiatives like the Program on Innovation and Entrepreneurship (PIE)—BC Law is situated in Boston, a city with a bustling startup ecosystem rich with ideas and talent, flourishing tech and life-science sectors, and obtainable early-stage funding that has birthed such consequential companies as Moderna, Toast, and Biogen.

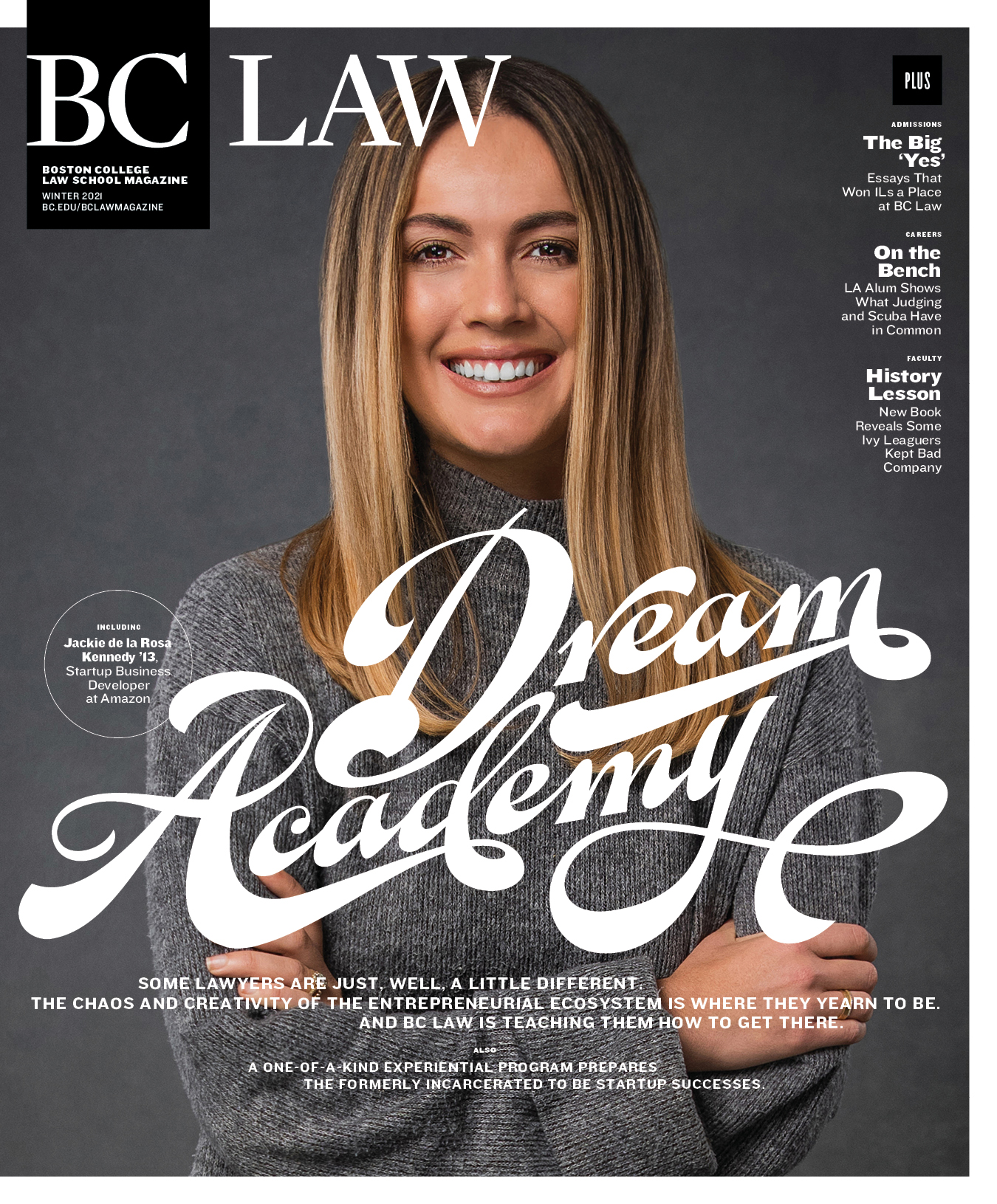

Among BC Law’s graduates are people like Hisao Kushi ’92, of Santa Monica, California, founding partner and chief legal officer of the exercise technology company Peloton; Kyle Robertson ’08, of Austin, Texas, founder and CEO of the artificial intelligence company NarrativeDx (recently acquired by Press Ganey); Mark Hexamer ’98, of San Francisco, founder of CiteIt! and Swap.com and currently a venture capitalist with Summit Partners; and, more recently, women like Floridian Jackie De La Rosa Kennedy ’13, who does Startup Business Development at Amazon and is a part-time venture capitalist with Afore Capital. With the proliferation of all things tech—fintech, adtech, healthtech, biotech—BC Law stands poised to launch the next generation of startup founders with law degrees.

Founding startups is “electrifying,” says Andy Miller ’93, of Palo Alto. Now CEO and founder of NRG Esports, Miller famously sold his startup Quattro Wireless to Apple in 2010 for $275 million and reported directly to Steve Jobs before returning to the startup world. “You have an idea, you talk to a bunch of people, you change your idea, you get going, you realize it’s not the right idea, but now you’re in the space and you’re smart in the space and you’re informed and it’s early,” he says. “No one’s going to know more about this than I am, so I’ve got as good a shot as anyone else to figure out if there’s something there.”

“At first, it seems counterintuitive for lawyers to start companies since we are trained to be risk-averse,” says De La Rosa Kennedy, “but I’m noticing more ex-lawyers leave big law firms to follow their passions, work for themselves, and build something meaningful.”

At this year’s Amazon Web Services’ AWS re:Invent global conference for technologists, Kennedy moderated a two-day session focused on helping women startup founders navigate the venture capital process. She herself entered the startup space after finding that she wanted to express more of herself than she felt the practice of law allowed. “Law school teaches you how to analyze problems, identify risk, and develop creative solutions based on those facts, while the practice of law, in my brief experience, was more confrontational and rigid,” she says. “I knew my strengths included creative thinking and a strong bias for action.” She took a course in entrepreneurial finance at Boston College’s Carroll School of Management, got a venture capital fellowship, and off she went.

The uncommon lawyers who found startups have a lot in common: Strong, irresistible interests beyond law. A knack for noticing an overlooked problem or deficiency or lurking injustice. Ingenuity. A spirit that thrives in chaos and risks. And an appreciation for the disciplined thinking they cultivated in law school. These lawyers sit within a global startup economy valued in 2019 at nearly $3 trillion.

“Entrepreneurs with JDs tell me that the training law school gives in deep, analytical thinking is invaluable for problem-solving in deep and systematic ways,” says BC Law Associate Professor David Olson. It takes a certain kind of personality, he notes, to be a successful startup founder. “You must have the ability to take risks, to be okay with chaos, to understand that you never have enough time to do everything, much less do it perfectly,” he says. Olson is the director of PIE, which supports research in innovation and entrepreneurship, hosts speakers, conferences, and workshops on important topics affecting the global economy, and works with students interested in cutting-edge global law and business issues.

A nice complement to PIE, the Entrepreneurship & Innovation Clinic exposes students to early-stage startup considerations and issues, whether that startup is a beekeeping business, an app developer, or an artist creating a charitable organization. For students with startup ambitions of their own, it can be instructive to observe their clients in action. “Our clients are fearless,” says Sandy Tarrant ’99, the clinic’s director. “Our students get a chance to see that up close and personal.”

At their core, BC Law’s newest crop of lawyers-turned-startup founders are gutsy inventors. Some invent things—new technologies or new pharmaceuticals. Some invent systems—new ways of doing business or new approaches to human challenges.

As an inventor of systems, Rebecca Sawhney ’13 uncovered a need to reform the nail care industry. Sawhney was an associate at a New York City law firm she had joined after graduation—enjoying it, but “craving something more creative than any kind of office life could ever give me,” she says.

Meanwhile, she was noticing that something was off about the experience of her weekly manicures. She started researching the nail care industry and learned that it was plagued by exploitative labor practices, poor hygiene, and toxic working conditions. That’s when it occurred to her to establish a new nail care brand, starting with a brick-and-mortar salon centered on fair labor practices and cleanliness. When she and her husband moved to the Bay Area, she opened Marlowe, a salon where workers are paid living wages with 401Ks and health care benefits—all practically unheard of in the industry. There’s an on-site clean room for hospital-grade sterilization. To keep the air healthy, they’ve rejected drills and unsafe nail applications.

By the end of its second year, Marlowe’s sales reached $1 million. But its fortunes changed with the pandemic, which is wreaking havoc on the global startup economy: Nearly half of all startups are direly short of capital, three-quarters are facing investor disruptions, and most are seeing precipitous drops in revenue. Sawhney, one of fifty women entrepreneurs awarded a 2020 Tory Burch Foundation Fellowship, vows she isn’t giving up. She’s looking at the current crisis as an opportunity: “How can we use this time during our second government-mandated shutdown to best prepare us to hit the ground running in the new year?” she said in December.

BC Law’s newest crop of lawyers-turned-startup founders are gutsy inventors. Some invent things—new technologies or new pharmaceuticals. Some invent systems—new ways of doing business or new approaches to human challenges.

Alphonse Harris ’15 had double-majored in physics and economics and came to law school with plans for a public interest career. Things changed when he was introduced to John Lewandowski, a PhD student at MIT. The two became fast friends and together co-founded Disease Diagnostics Group (DDG) while Harris was still in law school. Harris describes DDG as a “social enterprise developing low-cost, point-of-care, diagnostic solutions for neglected tropical diseases.” Lewandowski is the scientist/product developer, while Harris was chief operating officer and general counsel. (Harris has since left the company.)

“Neither of us had any experience working at a medical device company prior to founding DDG,” Harris says. Knowing that they needed help and where to find it became their superpowers: “The fact that we were inexperienced set us up for success,” Harris says. They built DDG by availing themselves of MIT’s mentoring services, receiving free legal services from a specialized program at a local university, and getting advice from their widening network of well-connected Boston-area people.

Britt St. George ’16 went to law school intent on becoming a sports agent. When she wasn’t laboring over casebooks, she was blogging and gaining traction as an early social media influencer—a market that hadn’t yet caught on in Boston. After graduating, she worked as in-house counsel for a fast-paced adtech company. There, she says, “I gained a wealth of experience about the inner workings of a business and acquired substantial knowledge of employment law, contract law, and numerous intangible instincts that would help me make the leap and found SMITH&SAINT a couple of years later.” Three years on, SMITH&SAINT, a Boston-based talent management and branding-building agency that St. George co-founded with her sister, boasts two niche talent markets—representing food bloggers and representing retired Olympic athletes—and St. George is fulfilling her dreams of helping others fulfill theirs.

Boosting Boston’s startup ecosystem is the Cambridge Innovation Center (CIC), where Stas Gayshan ’09 works as managing director. CIC provides space for emerging startups to come together in a thriving community of networking and ideas, where they share resources like labs, business equipment, conference rooms, and professional development opportunities.

Gayshan is also general counsel of CIC Health, a CIC subsidiary that helps individuals and organizations get access to fast, affordable COVID-19 testing. Gayshan notes that his law degree and business experience get him heard by the powers-that-be whose influence on policy and legislation can fortify—or hinder—the startup environment. “I understand the way that regulations affect actions. If you want to create a financial system that works for people, you have to think deeply about the rules,” he says. “If you are engaging in a conversation with a business group about crafting business engagement strategies that give opportunities to startups, it’s much more productive to come to that with a business and legal background.”

Returning to Landon Stinson, the law student at the beginning of this story who was seemingly interested in too many things: He had an epiphany during the summer of his 2L year. He was working at a Boston personal injury law firm, where his job was to sit day after day in a windowless basement room and request medical records and bills. “I found out two things,” he says. “Number one is that requesting medical records and bills is miserable. It’s a tedious and time-consuming process that is incredibly inefficient. Number two is that securely accessing your own health records or having your lawyer securely access your health records with your permission is vitally important. And I think it should be a basic human right to have that access.”

And then he realized: This job could be done by machine.

With encouragement from a couple of BC Law professors, Stinson hired a software developer to engineer a legal tech solution: an app that automated the process of ordering medical records and bills. Stinson called it Candle Request, and, before he graduated, he founded his business Candle Software, Inc. Candle has since also developed Billy, a legal tech app that helps personal injury lawyers keep track of their clients’ liens and medical bills.

While running Candle, Stinson, who lives in Florida, also has his own law firm, Beacon Legal PLLC, where he concentrates on personal injury and property matters. In line with his access-to-justice ethic, Stinson uses flat-fee and contingency-fee billing to keep his services affordable. “The law firm gives me an opportunity to do what I love—practice law—while also keeping me fresh on the inefficiencies that lawyers face,” he says.

Spoken like a true startup founder: After all, hidden in those inefficiencies are new legal tech products that haven’t been invented yet.