A panel of public health experts gathered on January 26 to discuss global vaccine inequality and the international human rights implications.

In the event co-sponsored by Boston College Law School, The BC Center for Human Rights and International Justice, and BC’s Schiller Institute’s Global Public Health and the Common Good program, the speakers stressed vaccines as among the most effective and cost-effective means of disease prevention. Access for all across the globe is essential.

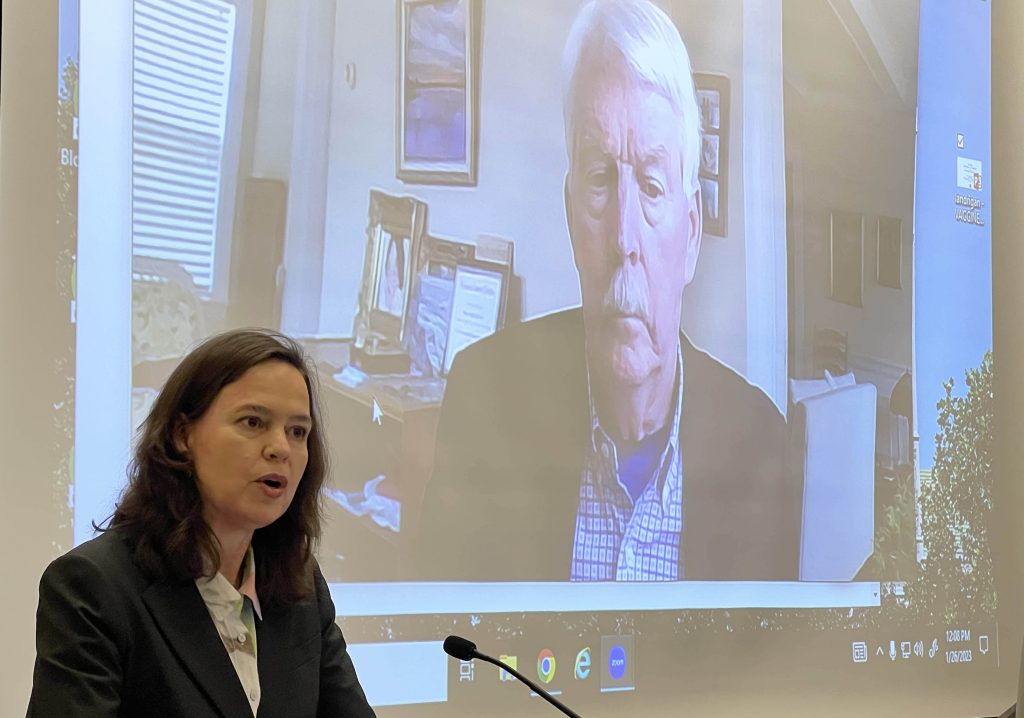

Katharine Young, associate dean of faculty and global programs at BC Law, moderated the event after a warm welcome by Dean Odette Lienau.

Dr. Phillip Landrigan, a pediatrician, public health physician, and epidemiologist, set the table by discussing the history of disease eradication throughout the world. Dr. Landrigan is also a professor of biology and director of the Global Public Health Program and the Global Observatory on Planetary Health with the Schiller Institute for Integrated Science and Society at BC.

According to Landrigan, the key elements of a successful vaccine program is that it is safe, cheap, and the vaccine is effective. Also essential, he said, are a disease surveillance program, trained personnel, a vaccine delivery strategy, and public education programs to spread the word about the vaccine. Finally, there need to be financial, legal, and policy mechanisms that allow people to have access to the vaccine.

Lisa Forman, associate professor and Canada research chair in human rights and global health equity at the University of Toronto, then stepped up to the podium to discuss the legal framework behind the human right to vaccine access.

“The majority of COVID vaccines have gone to wealthier countries, while the smallest number have gone to lower income countries,” Forman said. “It’s largely because high income countries have bought up the availability of the vaccines, and there are simply not enough to go around.”

Forman focused on general comments and statements by the Committee on Economic, Social, and Cultural Rights (CESCR), which that states that access to essential medicines and vaccines is a core obligation under the right to health. Under Article 15, there is a state duty to “prevent unreasonably high costs for access to essential medicines … from undermining the rights of large segments of the population to health.”

In 2020, CESCR explicated a right to access safe, effective COVID-19 vaccines based on the right to health and the right to benefits of scientific progress. Comments and statements are persuasive, but not binding, Forman said. International bodies, like the UN, have begun addressing the importance for affordable medicines and vaccine equity. But the world has only just begun the early stages of codification. The US often does not sign on or ratify global treaties related to the right to health. But it is an outlier.

“Countries should have paid better attention to the need of other countries. The question of ‘What are my duties to those outside my borders?’ fell off completely,” Forman added. “We could have hoped for something different, but we didn’t see it.”