Clearly, it was just a bad dream. Jenny Xi, who was six years old when enforcers of Mao’s Cultural Revolution ransacked her home and evicted her family, was simply navigating ancient anxiety while half asleep. Only her unconscious could conjure visions so contrived and preposterous at sunrise on a late-spring morning. In America.

A dozen or so Kevlar-clad government agents with a battering ram were inside her suburban Philadelphia home. Pressing her husband into a wall, they cuffed his hands behind his back near the master bedroom as others trained their weapons on Mrs. Xi and her children. The fantastical scene concluded as the FBI paraded Xiaoxing Xi, PhD, out into the daybreak of the family’s Penn Valley neighborhood, down the sidewalk, and into a vehicle that drove him away.

If only it had been a dream. Jenny Xi’s husband, the Interim Chair of the Physics Department at Temple University, was facing eighty years in federal prison for allegedly sharing secret information with a foreign government.

Seven months before the Xis’ terrifying home invasion, Sherry Chen swung into the driveway of a low-slung brick building surrounded by Ohio farmland that housed the National Weather Service office in Wilmington, about an hour’s drive east of Cincinnati.

En route to her desk, Chen, a hydrologist and expert flood-forecaster, was summoned by her boss and informed by six FBI agents that the government suspected she was a spy. Chen was placed in handcuffs, led past her co-workers, and taken to Dayton’s federal courthouse forty miles away. At that point, she was informed that she faced forty years in prison and $1 million in fines for illegally downloading data detailing “critical national infrastructure” from a restricted government database, and for making false statements.

Xi (pronounced Zschee) and Chen have only two things in common. They are both naturalized US citizens in their late fifties who were born in China. And, they were both innocent victims of flawed and problematic investigations that led to their indictment by a grand jury.

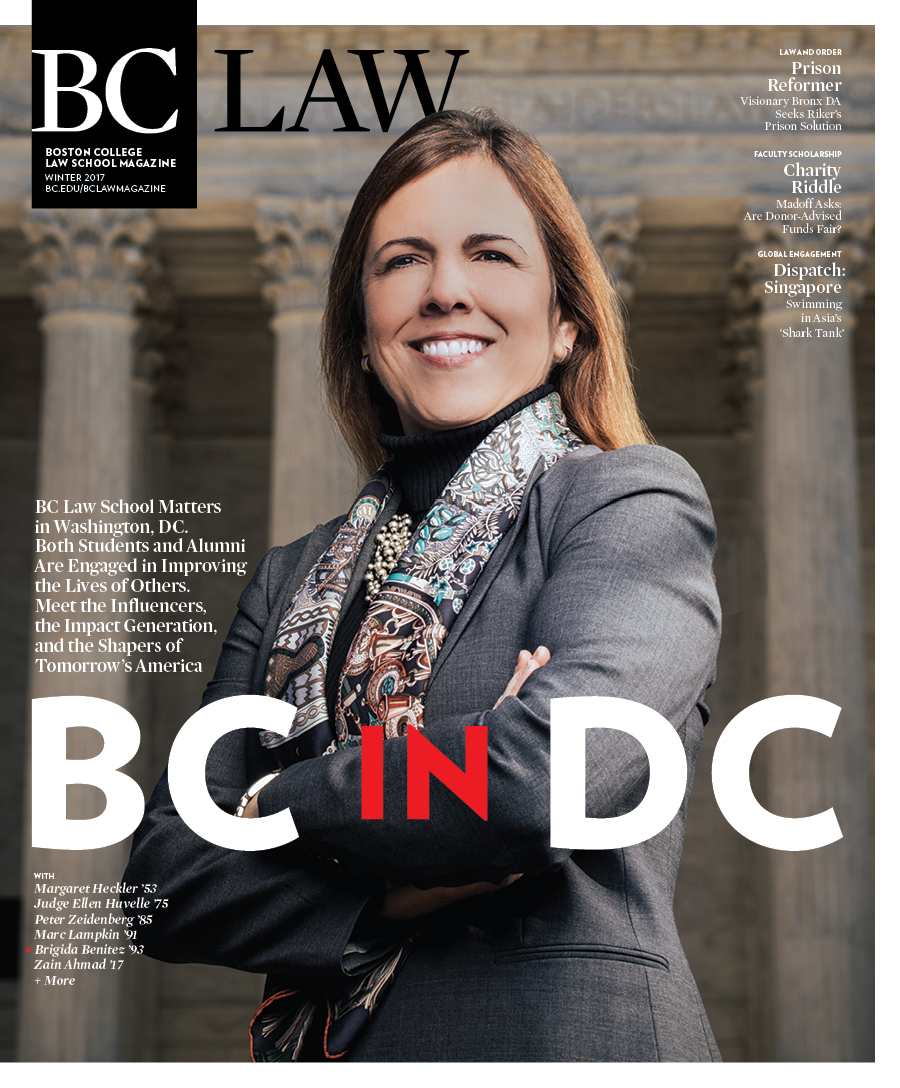

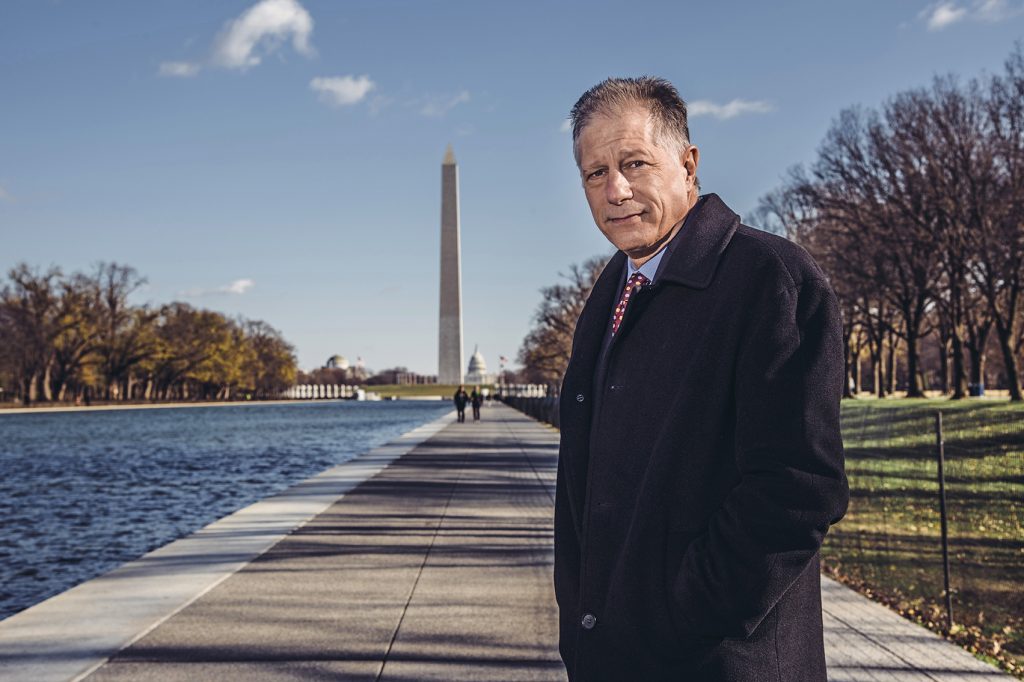

That is, until their lawyer, Peter Zeidenberg, a partner at Arent Fox who’s spent the bulk of his career in DC, provided them with a third shared experience by persuading the respective federal prosecutors to withdraw the charges.

Having spent seventeen years as a federal prosecutor at the US Department of Justice before entering the private sector, Zeidenberg was no stranger to high-profile cases. He was part of the prosecution team in the CIA leak grand jury investigation that led to the 2007 conviction of Lewis “Scooter” Libby, Vice President Dick Cheney’s chief of staff. Zeidenberg was also the lead trial counsel in the case that ended with the 2009 conviction of David H. Safavian for his role in the Jack Abramoff General Services Administration lobbying and corruption scandal.

“When Peter stepped into [the Chen case], I think I said to him something like, ‘Welcome to the club,’” says Brian Sun, the partner-in-charge at Jones Day’s Los Angeles office and a nationally renowned trial lawyer specializing in white-collar criminal defense. “There aren’t too many of us around the country who do this stuff.”

Sun and Zeidenberg are indeed in select company, and outnumbered by a growing subset of clients—Chinese Americans being prosecuted for economic espionage, trade-secret theft, or under a variety of other federal statutes.

The surge in criminal proceedings originated with a directive from the top. In his 2013 State of the Union Address, President Obama noted the broad strokes of a new Department of Justice strategy to combat intellectual property theft by foreign countries and companies. The key element was intensified investigations and increased prosecutions.

Justice Department prosecutions under the Economic Espionage Act, as the New York Times reported in 2015, jumped more than 30 percent in 2013 and, during the first nine months of 2014, such indictments increased an additional 33 percent. More than half of the economic espionage indictments between 2013 and the spring of 2015 had a China connection.

Remarkably enough, Zeidenberg’s entrée into this new niche practice was a matter of chance. A first-year patent lawyer at Arent Fox, who happens to be Chinese American, was contacted by an acquaintance of Sherry Chen’s brother in China. The patent lawyer sent around a group email within the firm about the case, and Zeidenberg jumped on it, flying to Ohio the next morning to meet with Sherry Chen. It was by way of Zeidenberg’s success with the Chen case that Professor Xi found him.

This past spring, the CBS News serial 60 Minutes reported that in the twenty-eight months between the start of 2013 and April of 2016, the DOJ had won convictions in fourteen cases related to Chinese economic espionage. That’s one every sixty days. The pitfall has been the substantial collateral damage. Zeidenberg says Xi and Chen are not outliers. They’re part of a pattern. Zeidenberg’s defense of Chen and Xi formed the foundation of the 60 Minutes episode.

“From my perspective [federal prosecutors] are casting way too wide of a net,” says Zeidenberg. “They are scooping in a lot of fish that should be immediately thrown back, and they don’t seem to realize it.”

From a federal prosecutorial perspective, there may be no more comparable example of failing to see the forest for the trees than the case the government built against Xi.

The day he was forcibly removed from his home, Xi was handcuffed to a table and interrogated by agents at the FBI’s Philadelphia field office. A newcomer to the judicial system, Xi freely answered questions without a lawyer by his side, replying “yes” to queries as to whether he’d ever “collaborated” in China or “visited Chinese labs.” Ultimately, he was accused of colluding with multiple government bodies in China as part of a years-long plot to acquire proprietary US technology.

Prosecutors claimed Xi emailed photos and blueprints of this technology to the Chinese. The government zeroed in on Xi’s work in the field of superconductors, which improve power transfer in multiple applications, including military. More specifically, he was accused of sending schematics to a colleague in China detailing an American-made device called a pocket heater—used to create a superfine coating that maximizes the flow of electricity. Xi allegedly did so despite his signed pledge to keep the design secret.

The US Attorney’s Office in Philadelphia also claimed Xi offered to build a state-of-the-art lab in China in return for distinguished and well-paid appointments as a quid pro quo.

Xi pleaded not guilty, used his house as collateral to post bail, and returned to his home the same day he was taken. His world crumbled.

Reporters staked out the Xi family home. Time seemed to slow, sleep came fitfully if at all. There were traumatic conversations about finding the money to hire and pay for a lawyer. Jenny Xi, a physics professor at Pennsylvania State University, steered clear of her own campus. Chummy Temple colleagues suddenly distanced themselves from her husband.

The school placed him on administrative leave and removed his title as interim department chair. He was advised to avoid contacting certain colleagues. As a consequence, Xi was unable to work on long-established research as it neared completion.

Though never formally accused of spying, Xi was ultimately charged with wire fraud for sending four emails to Chinese associates in 2010 about building a laboratory. If convicted, he was told, he could go away for life

Shortly after Zeidenberg got involved, it became clear that the evidentiary foundation upon which the government had built its case was, in a word, spongy.

To begin with, the freedom to communicate with Chinese scientists was a stipulation of one of Professor Xi’s National Science Foundation grants. More importantly, the device Xi was discussing with his academic counterparts in China was not a pocket heater, but rather a different heating technology that Xi, himself, was developing and planning to publish a paper about.

In an unmistakable rush to judgment, the government evidently never consulted experts in the field prior to presenting the case to a grand jury.

“Whenever you incentivize prosecutors and investigators to bring a particular type of case, it’s inevitable that you get screwed up prosecutions like this,” says Zeidenberg. “They have blinders on at the moment and if someone’s got a Chinese connection, they’re going to drop everything and try to find something. That’s not to say there isn’t a reason for government concern [in this realm]. It’s just that the medicine can be more damaging than the deeds. If you overreact, then you’re creating more harm than you’re preventing.”

There is no debating that Xi was harmed. It cost him $200,000 to clear his name. Temple University took him back, but the department chair job he claims he’d been promised the same week as his arrest was no longer on the table. “I see dangers all over the place,” he told the Philadelphia Inquirer this past April. “I think I sound very annoyingly paranoid when I talk to my colleagues because I tell them, ‘You better be careful, what you’re doing is dangerous.’”

Be that as it may, Zeidenberg did help Xi sidestep the doomsday scenario. But how? It’s not like a defense attorney would phone up a prosecutor and say, “We should meet. You’re about to get embarrassed in court.” Yet, that’s exactly what Zeidenberg did. Minus the bravado, of course.

“You call them and set it up and, you know, good prosecutors always want to hear what you have to say,” says Zeidenberg. “Only an idiot wouldn’t want to know what he or she will be facing at trial. Then, a lot of work goes into preparing for that meeting.”

Zeidenberg chose PowerPoint as his medium and anchored his advocacy in affidavits he’d solicited from scientists around the world, all of whom agreed that Xi’s blueprints were not related to a pocket heater.

“We secured half a dozen affidavits,” he explains. “These scientists were all over the world. Getting hold of them wasn’t easy. And they were very meticulous about what they would and would not say. Fortunately, they were all very eager to help. These people weren’t being paid, they just were willing to help.”

One particular affidavit from an engineer named Ward S. Ruby torpedoed the government’s case almost entirely on its own. In the course of conveying his bona fides relative to identifying whether something was or was not a pocket heater, Ruby’s sworn testimony read, “I am very familiar with this device, as I was one of the co-inventors.”

“When you have the guy who invented it saying, ‘That’s not my thing,’ what are you going to say about that?” notes Zeidenberg, regarding the Ruby affidavit. “We were able to demonstrate that Ruby’s device operated on an entirely different principle from Professor Xi’s. They were only similar in that they both got hot. It’s like a CD player and a phonograph. Both play music, but the similarity ends there. They work completely differently.”

In the end, the US Attorney accepted that the emails represented the kind of international academic collaboration that governments and universities attempt to foster, and that the technology involved was neither sensitive nor restricted.

Once the actual science proved that Xi’s communications were about a different device, it was game, set, match. Prosecutors withdrew the charges against Xi within a month of the meeting, in October 2015. It was the second time in a seven-month period (the Chen case being the first) that Zeidenberg had an espionage-related trial that did not go forward.

“Cases simply do not get dismissed,” he explains. “That’s what was so remarkable about this. Getting two cases that were indicted voluntarily dismissed, I mean, if you’ve got one of those in your career you talk about it ‘til your grave: ‘Gather around, let me tell you about the time I convinced them to dismiss the case.’ Getting two of them within [a few months], you know, it’s like winning the lottery twice. That said, I feel horrible for these people who were caught up in it. What permeated the atmosphere of [the Xi and Chen cases] was the sense that, apparently, they wouldn’t have been brought but for the fact that they were Chinese Americans and they had associates within China.”

Court documents in the Xi case reveal that the Justice Department said that “additional information came to the attention of the government” as a reason for dropping the charges.

“I feel like Peter is a great champion of this,” says Michael A. Schwartz, a partner at Pepper Hamilton LLP, who served as Zeidenberg’s local counsel on the Xi case, whose professional focus is criminal defense. “He’s a passionate advocate. He understands how difficult it is to represent a person who is accused, but presumed innocent, when the government brings untested charges against them. I’m very proud of the fact that the prosecutors in this case ultimately decided to do the right thing and dismiss the case.”

Although Zeidenberg was initially surprised the DOJ would present such a case to a grand jury, in the months since Xi’s exoneration, he finds himself less surprised. “I’ve got two more cases where the same thing has happened subsequent to [the Chen and Xi cases],” says Zeidenberg.

“Getting two cases that were indicted voluntarily dismissed, I mean, if you’ve got one of those in your career you talk about it ‘til your grave: ‘Gather around, let me tell you about the time I convinced them to dismiss the case.’”

In building its case against Sherry Chen, the DOJ moved in a much more deliberate fashion, spending more than two years from inception to issuing charges. The impetus was the notion, at least initially, that prosecutors could make a full-blown economic espionage case against her.

Given the resources dispensed on what turned out to be a fool’s errand, the case against Chen—a woman who made an eighteen-year career of developing and maintaining potentially life-saving flood forecasting models—could be characterized as an even bigger bungle than the Xi indictment.

The facts of the slow-moving investigation were nuanced.

Mainland China—Late summer, 2012: Xiafen Chen, who earned her advanced degrees in hydrology in Beijing, made her annual trip to China to visit her parents. During her stay, a nephew implored her to connect with an old classmate, a Mr. Jiao, vice minister of China’s Ministry of Water Resources, to help smooth over a dispute that his fiancée’s father was having with provincial water officials. Reluctantly, Chen reached out and Jiao’s secretary arranged a fifteen-minute meeting in his downtown offices. Jiao offered to intercede. Before they parted, Jiao mentioned an ongoing project to fund repairs to China’s reservoir systems and asked how such initiatives were funded in the US. Chen did not know the answer, but was curious to find out.

Wilmington, Ohio—Late summer, 2012: A diligent and inquisitive worker, Chen just a year earlier had won an award for a forecast that helped save the city of Cairo, Illinois, from record flooding. Upon returning to the US, she set out to answer Jiao’s question and ultimately sent Jiao an email containing website links, none of which were applicable to his question. Jiao took a week to respond with a perfunctory note of thanks. Chen also looped in Deborah H. Lee, the current Army Corps of Engineers’ chief of the water management division, with whom Chen had collaborated on multiple occasions.

Lee directed Chen to the ACE website and volunteered to answer any further questions from Jiao directly. Consulting the ACE database, Chen found nothing suitable for Jiao, but downloaded for herself data about Ohio dams she thought might be relevant to her forecasting model.

In a second email to Jiao alerting him to Lee’s offer, Chen included a link to the database and noted that “this database is only for government users, and nongovernment users are not able to download any data from this site.” Once again, Jiao responded: “Thanks a lot.” That was the extent of their communication. Shortly thereafter, Lee reported her correspondence with Chen to security staff at the Department of Commerce, which oversees the National Weather Service. The email read: “I’m concerned that an effort is being made to collect a comprehensive collection of US Army Corps of Engineers water control manuals on behalf of a foreign interest.”

Wilmington, Ohio—June, 2013: Two special agents from the Commerce Department arrived at Chen’s workplace and interrogated her for seven hours. They wanted to know about her meeting with a Chinese official in Beijing and why she accessed the National Inventory of Dams. The database, maintained by the Army Corps of Engineers, is available to government workers and members of the public who request login credentials. A subset of the data on the site (six of seventy data fields) carries restricted access to government workers only. Chen’s credentials allowed her full access to the database, but she didn’t have a password, since the last time she accessed the site was before the government began requiring passwords in 2009. In researching an answer to Jiao’s question back in 2012, she had asked a colleague in the adjacent cubicle, who had already provided the password and login instructions to the whole office, for assistance. He emailed her the password. Agents grilled her about her acquisition of the password and her meeting with Jiao. Asked to place the date of that meeting, she replied: “It was the last time I visited my parents, I think 2011. May 2011.”

Wilmington, Ohio—September, 2013: The day after returning from a four-week visit to her parents (her father, who was in poor health, died during the trip), she was interviewed for a second time by Commerce agents.

Washington, DC—July, 2014: An FBI memo of which Chen was the focus identified the Army Corps of Engineers as a “victim” of economic espionage by the People’s Republic of China.

Newark International Airport, New Jersey—September, 2014: As they were boarding a flight to Beijing, Chen and her husband were stopped and their bags were pulled from the plane and searched. They were released to re-board after an hour.

Wilmington, Ohio—October, 2014: The day after returning from the China visit, Chen was arrested by the FBI at her National Weather Service office.

Prosecutors had hunted long and hard for evidence of espionage, but failed to find any and settled on eight lesser counts, including false statements and two counts of theft. Chen suffered the same indignities as Xi following her arrest. She was suspended without pay from her job. Her family in China was forced to pony up for her legal defense. Media besieged her home, hoping for footage of a foreign spy embedded in an Ohio suburb of fewer than 13,000 residents. Friends and colleagues feared any interaction with Chen.

Once again, Zeidenberg was baffled by the government’s carelessness. Chen’s alleged “false statement” (and associated counts) was her mistake in saying “2011” instead of “2012,” as she answered agents’ June 2013 questions about her date of travel to China during the trip she met Jiao (an error she corrected later in the interview). The theft counts arose from the dam data she had downloaded to her computer, which she never sent to anyone.

“I never understood how she could be stealing it when it’s still on her computer,” says Zeidenberg. “I mean, that’s just sort of law school 101 property criminal law. Shouldn’t there be some exportation and intent to deprive, permanently, on her part? How can that be when it’s still sitting there? She downloaded the same [data set] twice, so there were two counts of theft. How can you steal the same thing twice?”

In Chen’s case, Zeidenberg didn’t need his PowerPoint slides.

“It was more like a [personal] appeal,” he explains. “It was just an explanation to the US Attorney [Carter Stewart, Southern District of Ohio], who I was convinced was unaware of exactly what was going on in his office [in this case]. I just wanted to communicate that this alleged false statement happened in the course of a single interview and was corrected by the end of the interview.”

Again, prosecutors seem to have inappropriately assessed their clues. If she were a spy, why would Chen return from China and inform her colleagues of her meeting with Jiao? Why would she direct her alleged Chinese contact to a chief of water management inside the US government? Why would she leave a blatant electronic trail in which she sought a database password? Why would a spy do that?

“If she were a spy, why would Chen return from China and inform her colleagues of her meeting with Jiao? Why would she direct her alleged Chinese contact to a chief of water management inside the US government? Why would she leave a blatant electronic trail in which she sought a database password? Why would a spy do that?”

The essence of Zeidenberg’s appeal to Carter Stewart was three-fold. First, the information Chen downloaded was not classified. Second, she never sent it to anyone. Third, the information never left her computer. Chen did send links to Jiao in China, but they were from a public website.

The government found it particularly fishy that the dam information Chen downloaded ended up not being material to her job.

“They claimed she didn’t really need it, but she downloaded information about Ohio,” says Zeidenberg. “That was her bailiwick. It wasn’t dam data from California. As it turned out, it wasn’t helpful to her job, but how many things do you read or cases do you look at or articles that you view that you don’t end up using? You just put it in another pile.”

In related interviews conducted by the FBI, Chen’s boss called Sherry Chen’s follow-through with the Jiao request “prototypical good employee-type behavior.” Zeidenberg conducted his own interview with the government employee who trained Chen, and her reputation for due diligence was reaffirmed. Zeidenberg encouraged authorities to talk to the man.

“In the end, I just sort of pointed out that this was a ridiculous case,” recalls Zeidenberg. “The week before, [former CIA Director] General David Petraeus got a misdemeanor for giving away code-word-protected secrets to his girlfriend and then lying about it to the FBI. Meanwhile, my client had downloaded information on her work computer from a work website and gave it to no one, and they’re charging her with a felony.”

Zeidenberg connected with the US Attorney’s office to deconstruct the case just one week before Chen’s trial was scheduled to begin in March of 2015. The charges were dropped the next day. A government spokeswoman told the New York Times that prosecutors had employed “prosecutorial discretion” in withdrawing the charges.

Following the flawed prosecutions of Xi and Chen, the DOJ amended oversight protocol to require that all espionage-related cases be approved and supervised by the DC headquarters. It is not a reform that Zeidenberg can celebrate. At least not yet.

For one thing, a year after her case was dropped, Sherry Chen was fired from her job for “untrustworthiness,” “lack of candor,” and other issues arising from her criminal investigation. Perhaps more chilling, the danger to Chinese Americans seems alive and well.

“I can’t say the change in DOJ protocol gives me any satisfaction,” says Zeidenberg. “I have another case that is pending right now in Tennessee…and it’s just as flawed and problematic an investigation in prosecution as my other cases and it did go through DC. I think that there has been a complete lack of vetting internally with the government in this case and that they’ve got their minds made up. I don’t see one iota of improvement.”