At thirty-one, a woman whom we’ll call Dawn Monteiro works as a hotel manager in a seaside resort town in southern New England. A single mother of two, she has completed one year of college with a 4.0 average, has entertained dreams of becoming a lawyer, and hopes to resume her education soon.

Monteiro is living a productive life, but go back fifteen years or so, and the picture is altogether different. In fact, from ages fourteen to seventeen, she was spending most of her time locked up. Her offense was a minor, even trivial one, but it has landed many girls in secure detention, often in a misdirected attempt to protect them from themselves or their surroundings. Having grown up in her state’s child welfare system, Dawn Monteiro had run away, time and again: from foster care, from residential programs, even from secure facilities.

For these infractions, Monteiro was thrown in “with girls who were in for attempted murder, for mayhem, for assault and battery,” she says. “It was scary. These girls would flip out and come after you. I was attacked a couple of times. Most girls in lockup are attacked.”

Monteiro, who admits having made poor decisions as a teen and young adult, likely would have spent an extra year in detention if not for the Juvenile Rights Advocacy Project (JRAP), a legal clinic at Boston College Law School, which took her on as a client at age fourteen. Over three years and many court hearings, student lawyers from JRAP, along with the clinic’s director and founder, Professor Francine Sherman ’80, argued that their client was a bright young woman whose potential was stifled in detention. Finally, a judge agreed and released her. (As with some other clients, Sherman has remained in Monteiro’s life, helping her find a place to live when she was homeless, advising her on her education, attending medical appointments during a high-risk pregnancy. “She’s been with me through all the good and the bad,” Monteiro says.)

Getting Monteiro freed from detention was a hard-earned win for the JRAP lawyers and a blessing for their client, but in Sherman’s view Monteiro should have never been locked up to start with—and might never have been if her name were Don instead of Dawn. The existence of large disparities in the charging and sentencing of boys and girls is one of many hard facts and critical insights that Sherman has collected during years of practice and added to the national conversation on how to fix the juvenile justice system. Her prescriptions for change, based on nearly three decades of work in the system, have not only influenced legal scholars and social science researchers, they have also helped improve the lives of hundreds of girls.

Sherman’s work as a lawyer, researcher, and change advocate puts her at the center of a large and growing movement of groups and individuals working for juvenile justice reform. Groups include big funders, academic centers, government agencies, legal and social service providers, and research and advocacy organizations; they range from the US Department of Justice and big national brand names like the MacArthur and Annie E. Casey foundations to statewide outfits like the Florida Juvenile Justice Association and Massachusetts-based Citizens for Juvenile Justice, which Sherman helped found. A few other players include the National Council on Crime and Delinquency, the Delores Barr Weaver Policy Center, the Justice Policy Institute, the Center on Youth Justice, and the Center for Juvenile Justice Reform at Georgetown University. Even police groups are getting involved, with the International Association of Chiefs of Police sponsoring a “leadership institute” this coming September that promises to give law enforcement executives “tools to…engage in effective collaboration on juvenile justice reform in their communities.”

When Sherman founded JRAP, in 1996, this big reform movement was still years away. Few academics or activists were devoting much thought to girls in juvenile justice back in the nineties, a fact that helped draw Sherman to the field. “I went to law school with the idea of making a difference,” she recalls, “and I thought that the time was right for the issue [of girls in the juvenile justice system]. Girls’ numbers in the juvenile justice system were increasing…and not a lot of people were focusing on it. Part of what helps girls develop in a healthy way is good relationships, and I thought a good relationship with a lawyer could be part of that.”

Sherman also saw JRAP as a way to channel help to kids who needed a break, having been born into poverty. In the clinic’s early days, when she’d just started working with court-involved girls, she and her husband were also raising two daughters. “The difference in the opportunities and life course of these young women was profound,” she says. “Here were my girls with every opportunity in the world, and they were no different from the girls I was representing.”

While emphasizing girls, JRAP accepts a broad range of cases on behalf of young people of both sexes, not just reducing their time in detention but also helping them access educational and mental health services, and anything else that allows them to get their lives on track: family therapy, a healthcare provider, a part-time job, a mentor. The model owes as much to social work as it does to law.

The existence of large disparities in the charging and sentencing of girls is one of many hard facts and critical insights that Sherman has collected and added to the national conversation on how to fix the juvenile justice system.

Sherman likes to remind the student lawyers at JRAP that for children in the justice and child welfare systems, small successes can make an enormous difference. She recounts the case of one teen, on the brink of dropping out of school, whose life was turned around when his JRAP lawyer had him moved to a specialized classroom for kids with his particular learning disability. Another JRAP lawyer arranged to place a client with his grandmother, and got the court to appoint her as his guardian. “He now calls his lawyer whenever problems come up. That’s the real success: the relationship,” says Sherman.

By the late 1990s Sherman knew enough about juvenile justice to start sharing her knowledge in articles and book chapters, guidebooks and reports, written and oral testimony to legislative bodies, appearances in media and on panels at professional conferences. Her guidebooks Detention Reform and Girls (2005) and Making Juvenile Justice Work for Girls (2013; coauthored with Richard Mendel and Angela Irvine), were published by the Juvenile Detention Alternatives Initiative (JDAI), a project of the Annie E. Casey Foundation, which has disseminated copies to personnel at some 200 state and county juvenile justice systems as well as to scholars and advocates. “For a while [the 2005 guidebook] was the only research we had on the lives of detained girls as well as opportunities for reform. We carried it around as if it was the Bible,” says Malika Saada Saar, executive director of the advocacy group Rights4Kids, who praises the 2013 guidebook as another vital tool for advocates.

Sherman has affected change more directly through her consultancies, mostly under JDAI auspices, with managers of juvenile justice systems around the country. Her work for JDAI starts from the principle that, considering its high cost, its emotional toll, and the non-punitive mission of juvenile justice, detention, especially of girls, should always be a last resort, used only when the presence of a child in the community threatens public safety. For one thing, three quarters or more of court-involved girls are suffering from trauma, the result of life experiences like being trafficked for sex or assaulted by a boyfriend or family member. And trauma, says Sherman, means “you have no power, that someone has reframed reality for you.…A lot of the running away you see, the misbehavior, the violations of rules are efforts to reassert control.”

Detention, of course, takes control away from the detainee, and thus it only adds to trauma. What is more, it disrupts girls’ relationships—with families, friends, physicians, schools. Girls do not respond well to rules, competition, and hierarchy, building blocks of the traditional detention regime; instead, they tend to thrive on relationships and trust. The alternatives proposed by JDAI, things like supervised release and night reporting programs, allow girls to maintain their relationships while receiving services in the community for themselves and their families. This model is being adopted in systems nationwide, including systems, from New England to the Midwest to California, with which Sherman has consulted.

In 2006, Sherman traveled to Nevada to work with top juvenile justice officials in Washoe County, including Reno and vicinity. Working from the JDAI model, she was “very data driven,” says Elizabeth Florez, a division director in the county system. “Instead of letting us give anecdotal responses, she challenged us to look at data.” What the data revealed—to the surprise of Florez and colleagues—is that the county was locking up a higher percentage of court-involved girls than the typical juvenile justice system, mainly for minor misdemeanors and small violations of probation conditions where the original charge was a status offense like running away or truancy. The data also showed that girls were often being held not for what they’d done but out of a desire to protect them, with large numbers detained even when the system’s own risk assessments showed they could be safely released to the community. And once in detention, many girls languished while awaiting psychological and substance abuse evaluations, typically delaying their discharge by weeks.

Sherman’s work in Washoe County led to small changes in policies and practices—small changes that brought dramatic results. For example, system managers rewrote their risk assessment policy to make it harder to override the assessments, and they reorganized clinicians’ schedules to shorten, from weeks to a day or two, the waiting time for mental health evaluations. They also ended probation for status offenses, thereby slashing the number of girls detained for minor probation violations. In addition, using data and analysis from Sherman, they successfully lobbied the state legislature to change Nevada’s domestic violence law so that girls arrested in domestic disputes were less likely to be held if they could safely return home or to a cooling-off site like a grandparent’s house. Before the change, detention had been mandatory.

Between 2006, when Sherman arrived, and 2010, the county’s daily census of girls in detention dropped by an astonishing 50 percent. During the same period, the county saw no increase in crimes by girls; indeed, it saw significant reductions in arrests of girls for felonies, gross misdemeanors, and status offenses. Ninety percent of girls in alternative supervision programs “don’t recidivate,” Florez says, “and almost all of them show up for their court dates.”

Sherman started working with Rhode Island’s juvenile justice system a few years after her trip to Reno. On her first visit, she and a handful of JRAP student lawyers were taken on a tour of the state’s shiny new detention center, says Kevin Aucoin, deputy director of the Rhode Island Department of Children, Youth, and Families. Sherman “thought the new facility was great,” he recalls, “but she asked, ‘Where are the girls?’”

She must have found the answer disheartening. While the boys were getting the benefit of the new facility, the girls were being warehoused a five minute walk away, in a dilapidated and ancient building once used as a mental hospital. Most services for the girls—healthcare, education, mental health—were run out of the new building, says Aucoin. “Even to go to the gym,” he says, “you had to line [the girls] up, get security, put them in handcuffs, load them into a van” and then undo the process at the other end.

After interviewing staff and detainees, Sherman and her students put together a report that helped persuade Rhode Island to change all that, arguing that, as the JDAI process advanced, the state would be detaining fewer boys, freeing up ample space for girls in the new facility. As a result, and with the blessing of budget-minded legislators, the old building closed, and the girls moved to a unit in the new one.

At the same time, as she had done in Reno, Sherman worked with Rhode Island officials to analyze their data on detained girls. As in Reno, they concluded “that a number of females were being locked up not because of their offenses or their risk of reoffending but for their safety,” says Aucoin. While the number of boys detained in Rhode Island has dropped by more than 40 percent since JDAI first went to work there, the number of girls has dropped by 80 percent, from twenty down to four. Meanwhile, state spending on juvenile detention has dropped by $3 million annually, a 19 percent saving when you adjust for inflation. And all this, says Aucoin, has happened “without increased safety risks for youth in the community.”

Massachusetts, like Rhode Island, has worked with JDAI to lower its numbers of youth in detention. In the last five years—a period when the age of adult jurisdiction in the commonwealth was raised by a year, diverting thousands of court-involved kids into the juvenile justice system—the state has nonetheless reduced its census of detained youth by one third, allowing it to close secure facilities, says Peter Forbes, director of the state’s Department of Youth Services. Forbes adds that he expects more big reductions in coming years. Five years ago, he says, “every kid in detention [in Massachusetts] was in secure detention, but now we have shelter care and foster care alternatives, and Fran was part of that conversation early on.”

Many of his recent conversations with Sherman have to do not with the system but with individual clients, though. “She’s really tenacious,” Forbes observes. “She has gone to the wall for individual girls, and it’s interesting to have a nationally known expert calling you to advocate for an individual girl.”

Interesting, certainly, but also telling, because it’s Sherman’s one-on-one relationships with girls that have made her so unusual and so valuable as a researcher. Having worked in the trenches with detained young people like Dawn Monteiro, Sherman “knows the girls,” says Jeannette Pai-Espinosa, president of the National Crittenden Foundation, a family of agencies supporting girls and young women. “They’re not just data to her. She sees them as part of the solution, not the problem, and she really understands the context of their lives.”

That understanding is responsible in large part for what colleagues see as Sherman’s biggest achievement: simply drawing the attention of people with power—not only scholars and advocates, but also prosecutors, judges, police, politicians, and probation and juvenile justice officials—to girls, and girls’ distinctive needs.

“To get girls to be a focus has required real effort because they’re a small part, around 15 percent, of [system-involved youth] and also because of simple inertia, because lots of juvenile justice systems don’t want to change,” says Mark Soler, executive director of the Center for Children’s Law and Policy, a juvenile justice reform organization. “Because of Fran’s work, lots of systems are thinking, ‘What kind of programs can we have for girls?’”

During thirty years as a feature writer for magazines and newspapers, David Reich has published profiles of nationally known political figures as well as articles on politics, business, science and technology, the arts, the law, and law enforcement. His novel The Antiracism Trainings was published in 2010, and he’s currently working on a memoir about serving as a late friend’s executor.

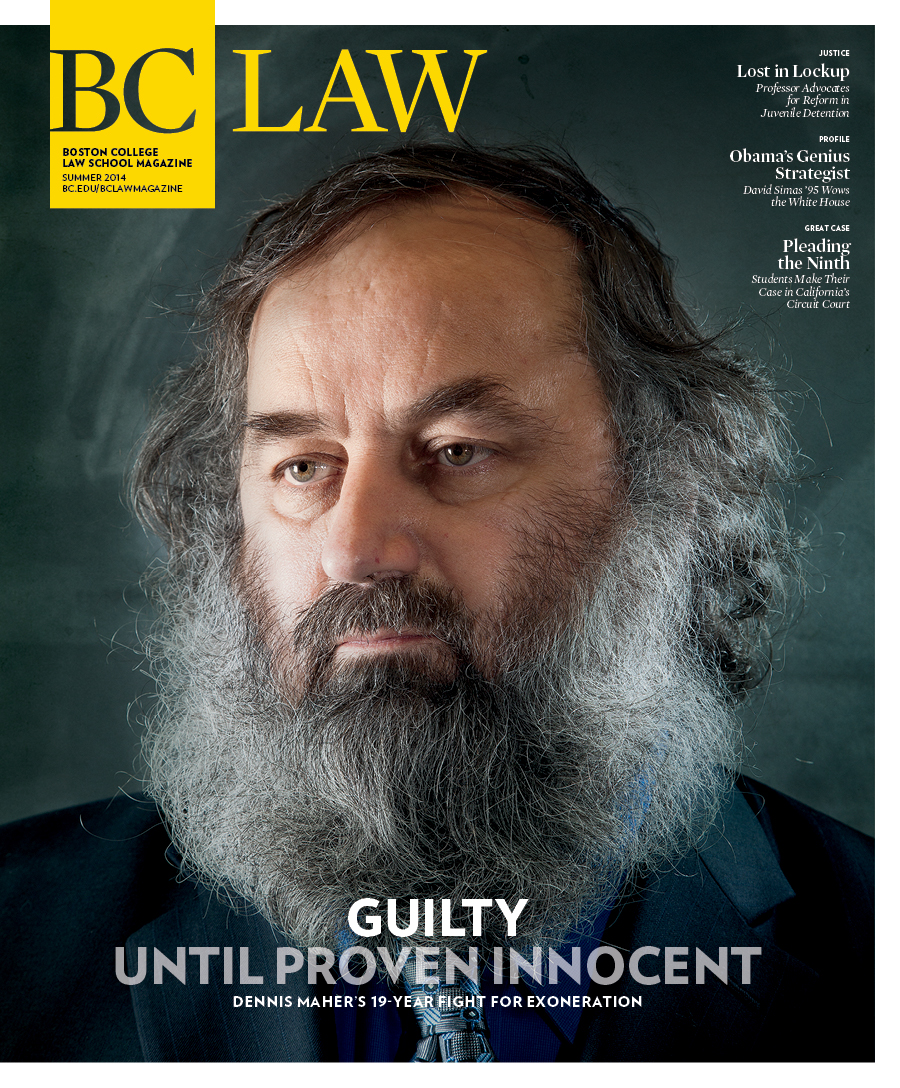

What the Eye Beholds

Richard Ross’ haunting images speak volumes about juvenile injustices.

Richard Ross, whose stark photos of incarcerated youth accompany this article, spoke at BC Law School on March 24. Introducing him at the event, Professor Francine Sherman told the audience that Ross’ work, which has appeared in Harper’s, the Guardian, the New York Times, and Mother Jones, “puts a face on a real problem that otherwise could be pretty abstract for people.” Ross, who teaches in the art department at the University of California, Santa Barbara, published Juvenile in Justice, a book of his photos of detained youth, in 2012. His upcoming book, Girls in Justice, is due out in January 2015. Images from both volumes are published with this article. To learn more about Ross’ new work, visit his website.

To view Richard Ross’ lecture, go to bc.edu/lawmagvideos.