In Hedberg v. Wakamatsu, SJC-12624 (July 11, 2019), the Supreme Judicial Court made a significant change in the Hearsay Rule applied in Massachusetts. Every trial lawyer knows that the prohibition against hearsay evidence excludes unreliable second-hand evidence that cannot be tested at trial by cross-examination. It is equally well recognized that the rule sometimes snares very probative evidence that does carry its own indicia of trustworthiness.

Such was the case when Leslie Hedberg sued her surgeon after a procedure in 2012 that left her with constant pain and serious neurological symptoms.

Her quest for just compensation was thwarted when the trial judge kept from the jury evidence of a conversation Hedberg said she had with the medical student who had assisted at the nearly four-hour surgery in which he admitted to critical mistakes in the positioning of her legs and said, “I’m awfully sorry,” repeated several times in response to her complaints about the pain and numbness.

Because the medical student testified that he had no memory of that exchange, the judge ruled it inadmissible under the controlling hearsay doctrine in Massachusetts. Ignorant of the statement, the jury came back with a verdict for the surgeon.

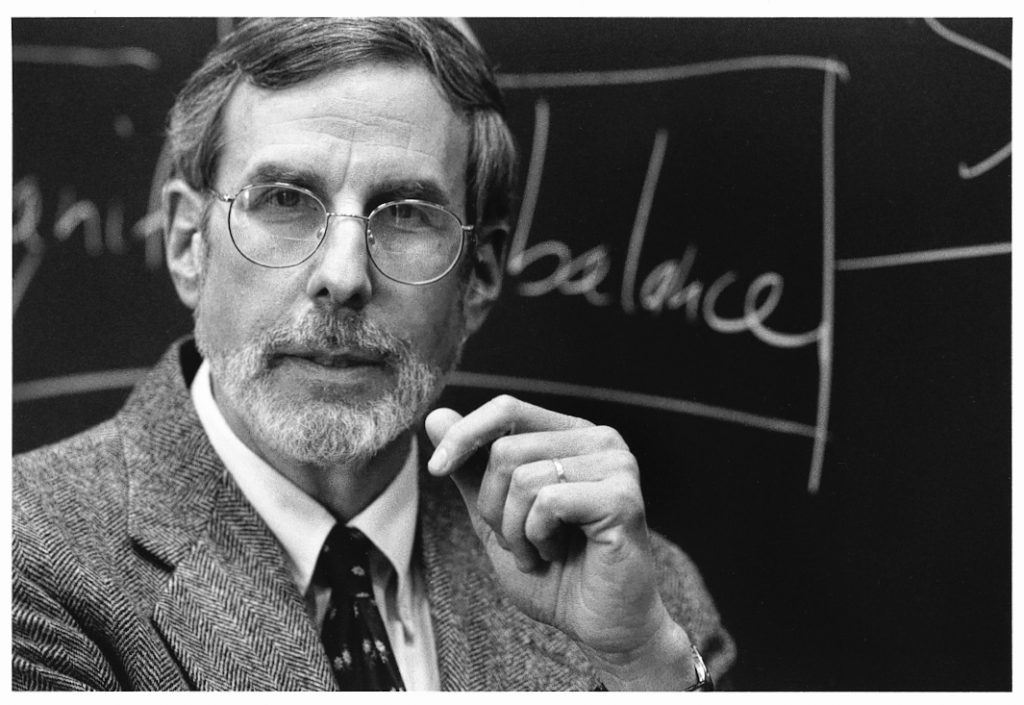

Well represented by Boston College Law School graduates Patrick Jones ’78 and Richard Paterniti ’99, and with the support of an amicus brief submitted by the BC Law Amicus Clinic authored by professor Thomas Carey ’65, professor and evidence expert Mark Brodin, and student Nickolas Merrill ’20, Hedberg argued for a change in the Commonwealth’s treatment of declarations against interest like the one in this case.

In an opinion by Justice David A. Lowy for a unanimous court released on July 11, the Massachusetts Supreme Judicial Court agreed and changed the common law of evidence in Massachusetts. It adopted the federal approach: A witness who lacks memory of a prior statement is deemed unavailable, opening the door to the admission of the statement if it falls within a well-established hearsay exception. The exception in this case is for declarations against pecuniary interest (assumed to be trustworthy because people don’t usually make statements that harm their interests or careers unless they believe them to be true).

“This is one of the most significant developments in Massachusetts evidence law in recent years, adopting a rule first proposed to the Court in 1980, and will provide future juries with previously excluded persuasive evidence to weigh in their search for the truth,” Brodin said.

For more on the Amicus Clinic and this brief, click here.