In the dynamic internet ecosystem, few players have been more active and influential lately than Comcast Corporation. After purchasing NBC-Universal in 2011 and entering an agreement to acquire Time Warner Cable earlier this year, the company signed an interconnection agreement with Netflix that allows the internet’s leading media provider to stream information more efficiently to Comcast consumers, for an undisclosed fee. Net neutrality advocates have condemned this agreement as a “pay for play” deal that threatens the free flow of information across the internet. But a more nuanced analysis shows little cause for alarm, while shedding some light on the intricate business relationships that govern the internet.

It is a misconception that Netflix and other internet content providers pay nothing to deliver content. In fact, content providers typically purchase internet transit service from several little-known companies such as Cogent and Level 3, whose wires are part of the “network of networks” that comprise the internet. These transit providers act as middlemen, charging content providers to deliver

traffic over the internet and then entering agreements with other networks, including broadband providers such as Comcast, to send that traffic on to consumers.

One can think of the Comcast-Netflix deal as an agreement to eliminate the middleman. Netflix generates one-third of North American internet traffic during peak hours. Its volume has overwhelmed the existing connections between Cogent, a Netflix transit provider, and the Comcast network. Reports suggest that Cogent refused to upgrade these connections, hoping Comcast would contribute to the cost. As Netflix’s quality deteriorated, the company signed a deal to interconnect with Comcast directly. The fees Comcast is charging are thus not a new expense for Netflix, but rather a decision to pay Comcast directly rather than transit providers to carry Netflix traffic to Comcast customers. Generally, agreements to eliminate a middleman are welfare-enhancing, and in this case, Comcast customers report better service because Netflix is no longer dependent on potentially overloaded internet bottlenecks.

As the Comcast-Netflix agreement illustrates, the internet is a complex ecosystem in which countless business transactions intertwine to bring information to consumers. Thus far, regulatory attention has focused primarily upon broadband providers such as Comcast, but they comprise only part of the system. Equally important within the network are transit and backbone providers such as Cogent and Level 3, and beyond the network itself, the internet also depends upon hardware providers such as Samsung, software companies such as Apple and Google’s Android, content providers like Netflix, and business-to-business companies such as Cisco and Amazon’s Cloud Services. All play an important role in transmitting information at the speed of light.

More importantly, these companies are constantly evolving, creating products and ways to deliver content.This dynamism is a good thing. Like a biological organism, the internet evolves in response to external stimuli to become stronger and better. And while Comcast appears to occupy a significant part of the market today, in this dynamic marketplace no position is stable. Fifteen years ago critics said the same thing about AOL Time Warner, a colossus that controlled internet access and content and yet withered away as nimble competitors provided better services more efficiently. In this environment, the only certainty is uncertainty, and the only path to long-term success is through constant adaptation.

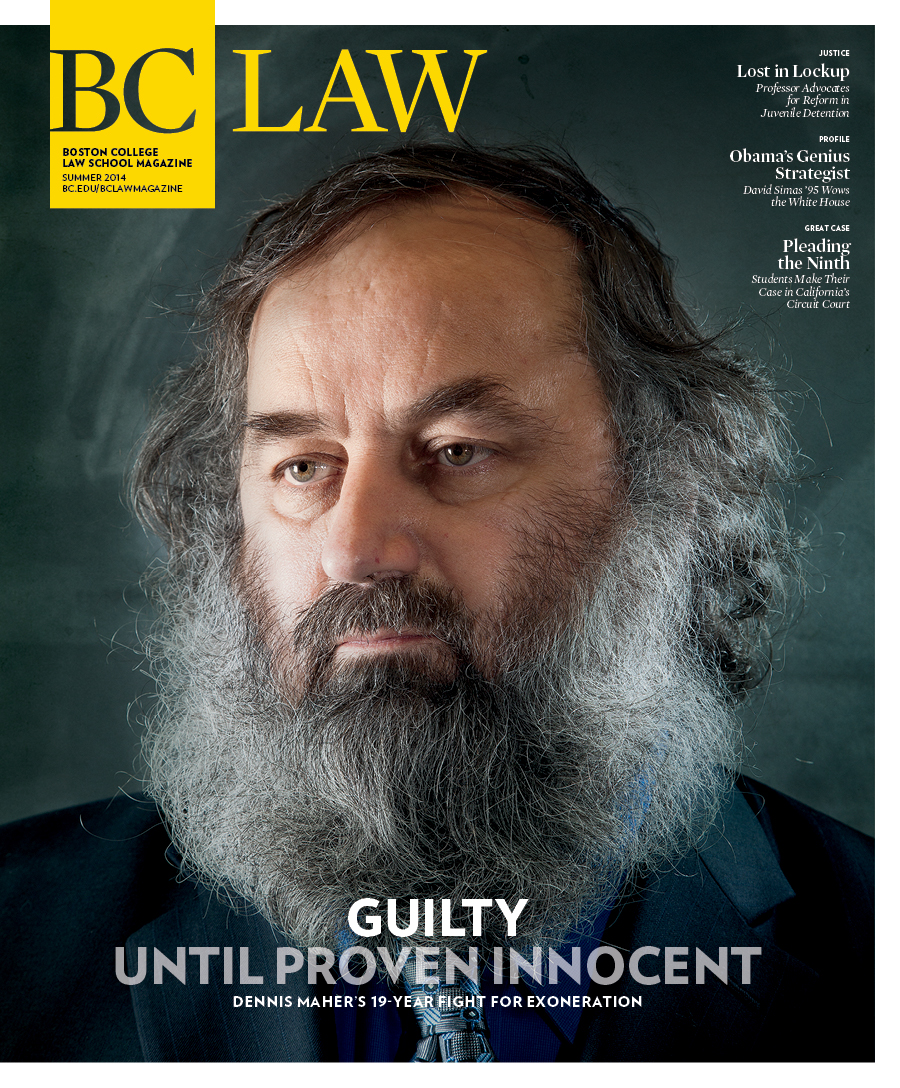

Daniel Lyons is an Associate Professor of Law. He writes frequently on internet governance issues and is a regular contributor to techpolicydaily.com.