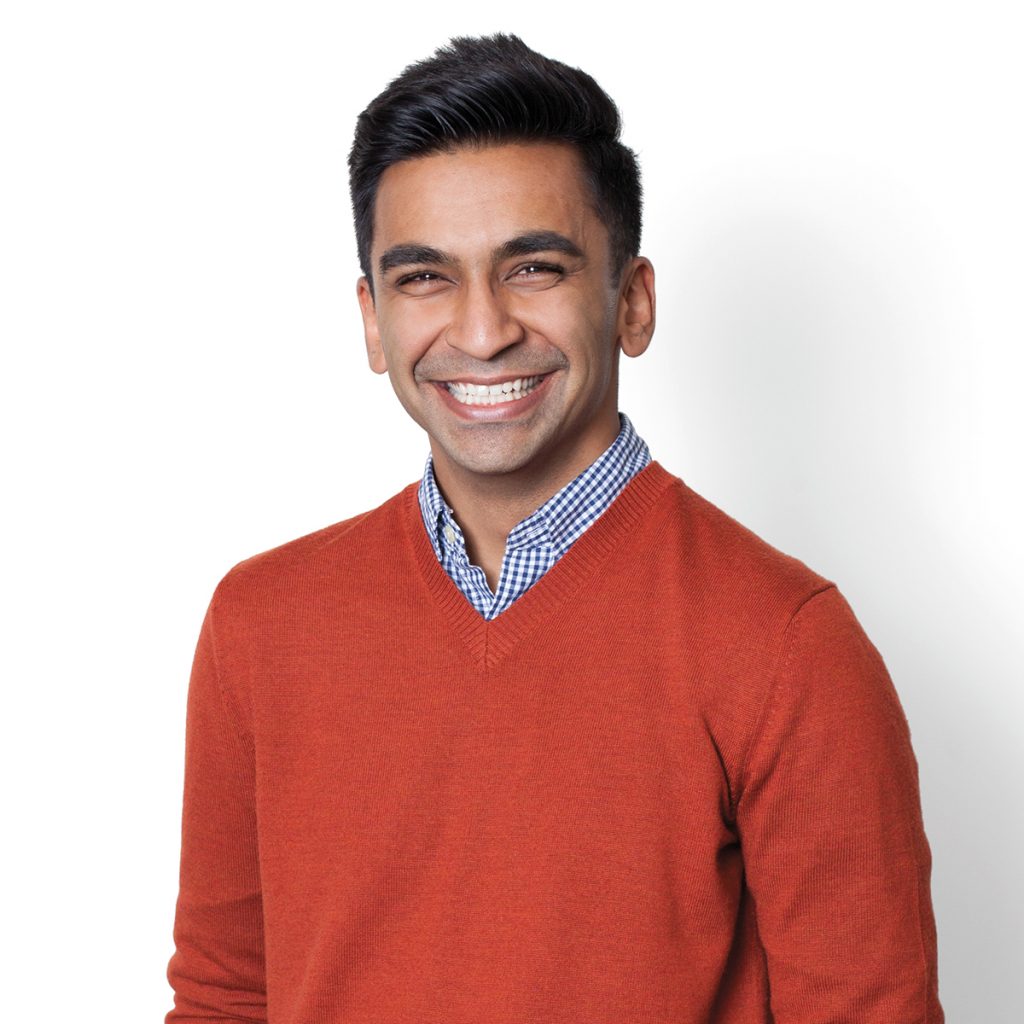

Most nineteen-year-old men do not find themselves with the responsibility of selecting someone else’s wedding cake, but then most sisters would not assign the task of planning a 500-person Pakistani wedding to their younger brother. And yet, there I was. I had never been in a real bakery before, and the woman running the shop eyed me warily, suspecting, I think, that she was in the middle of a prank. When she asked why I was there, I explained that I was picking out a cake for the bride, my sister. She asked with clear disdain if my bride was my sister. Thus began the wedding planning that would control my life for several months. I settled on a five-tiered cake with vanilla frosting and strawberry filling, reflecting the respective favorite flavors of my sister and her fiancé; then it was on to centerpieces, aisle decorations, choreographed dances, and decorators.

Nothing went according to plan on the wedding day. The cake, when it arrived, was a mess. The rose petal number I ordered showed up as a slightly lopsided pile of icing, and the South Asian bride and groom cake topper was conspicuously absent. The florist brought artificial flowers for the aisles instead of real ones and the stage decorator was three hours late. When the banquet hall’s fire alarm went off an hour before guests were scheduled to arrive, I nearly stayed inside to continue setting up, but thought the better of it given the small but real possibility that there was actually a fire. And yet, when my sister walked down the aisle, I had tears in my eyes, as did everyone else. When she and her groom fed cake to each other, the vanilla frosting and strawberry filling were perfect. In her eyes, and the eyes of the guests, the wedding was a rousing success.

My family often looks to me to implement solutions to difficult problems, and just as often, I volunteer. To me, the most interesting problems are intricate and multidimensional, and they allow for similarly multidimensional and innovative solutions.

In roles ranging from brother to student to paralegal, I have had opportunities to pursue solutions of that sort. As a high school senior, I wrote and directed a play about differences and commonalities in South Asian communities, recruiting students of both Indian and Pakistani heritage to perform it. As the chair of my university’s allocation board, I used my position to spark collaborations among various religious and cultural organizations. From bridging structural and cultural barriers to planning a wedding, I thrive on designing and implementing solutions to the issues I care most about.

I was in sixth grade when 9/11 happened. My identity as both an American and a Muslim changed the day the towers fell, and my nation’s subsequent response, both domestic and international, highlighted a need for dialogue and creative thinking. From that point forward, I began to look in earnest for a means of addressing the structural problems I saw around me.

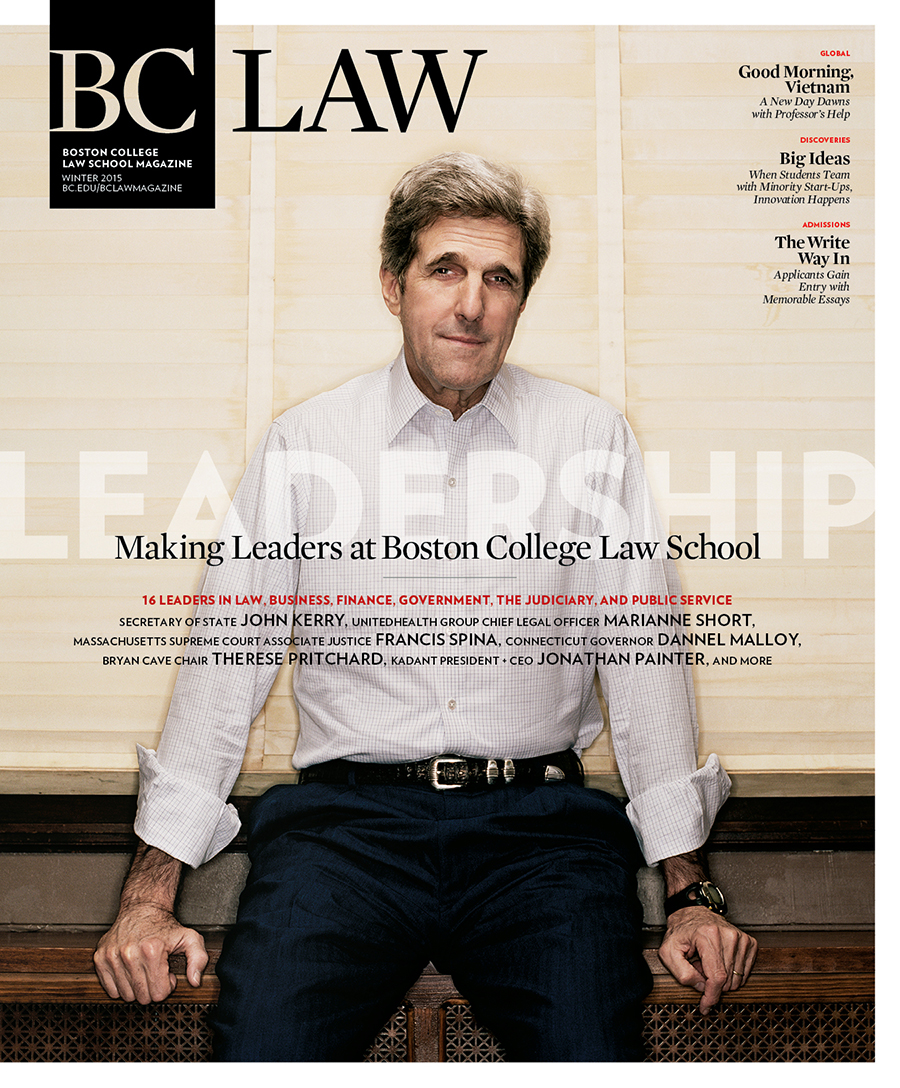

I have come to see law as a means of creating concrete solutions and as a skill set to advocate for change. I can think of no better platform than law from which to address the challenges facing my community and my country, and no better place to start than with an excellent legal education.