September 17, 2015—Constitution Day—marks the 228th anniversary of the signing of the U.S. Constitution. It is a non-anniversary. An appropriate moment to emphasize that James Madison did not know that he was helping to write the Constitution. Madison and his fellow delegates could not perceive the extraordinary document that the Constitution would become. James Madison’s original Notes—not the revised version with which we are familiar—guide us back to a moment when the substance and fate of the Constitution remained uncertain.

To a remarkable degree, Madison’s revised Notes created the narrative we inherit of the Convention. Hundreds of books and articles have been written on the Convention. They rely on one manuscript: Madison’s Notes. In 1840, after Madison’s death, Dolley Madison published his Notes. They remain the authority for scholars, historians, journalists, lawyers, and judges.

Madison’s Notes are the only source that covers every day of the Convention from May 14 to September 17, 1787. No other source depicts the Convention as Madison’s Notes do: as a political drama, with compelling characters, lengthy discourses on political theories, crushing disappointments, and seemingly miraculous successes. The Notes are, as the Library of Congress catalogs them, properly considered a “Top Treasure” of the American people.

But the Notes do not date in their entirety to the summer of 1787. They are covered in revisions. This fact is known – but the number is a shock. When I saw the manuscript in the conservation lab at the Library of Congress—in the aptly named Madison Building—the additions appear in various ink shades, with handwriting, some youthful, some with the shake of Madison’s later years. Madison even added slips of paper with longer revisions.

The revisions do not detract, but enhance Madison’s manuscript. Madison’s Notes were revised as he changed his understanding about the Convention, the Constitution, and his own role. Madison’s Notes were originally taken as a legislative diary for himself and likely Thomas Jefferson. They tracked his political ideas, his strategies, and the positions of allies and opponents. The original Notes reflected what Madison cared about.

I love talking about the Notes with students because they know that one cannot take notes of oneself speaking. When they are called on, they either leave their notes blank or they compose that section later, reflecting what they realized afterwards was the right answer. Madison’s own speeches are thus the most troubling in terms of reliability. In fact, in the years immediately after the Convention, he likely replaced several of the sheets containing his speeches in order to distance himself from statements that became controversial.

Madison never finished the Notes that summer. In late August, as the Convention debated the first draft of the Constitution, the delegates sent controversial issues to committees. Madison served on the three most important committees: dealing with slavery, postponed matters, and the final draft. Moreover, he became sick—something that he seemed susceptible to under stress.

Madison stopped writing the Notes. He was too involved in drafting to bother with a diary. Moreover, he likely could not keep distinct decisions made in committees and those in the Convention. Thus at the very moment when the Convention decided many of the issues we debate today—certain congressional powers, impeachments, the vice-president, the electoral college, presidential powers—and the groupings and relationship that converted twenty-three articles into the final seven—the Notes are the most unreliable. Yet this collapse of the Notes reflected the contemporary inability of the delegates to see the final Constitution in the sense that we mistakenly imagine they could.

Two years would pass before Madison composed the final weeks of the Notes. By then, his rough notes were difficult to decipher. Moreover, the Convention had begun to acquire a different set of meanings. As a member of the first Congress, Madison had repeatedly confronted the difficulties of interpreting the Constitution. When he went back to finish the Notes, he secretly acquired the official journal of the Convention from George Washington and used it. The focus on text in the last weeks of the Notes reflected the politics and concerns of 1789.

Beginning in 1789, Madison began to revise the Notes to convert his diary into a record of debates. Along the way, he converted himself into a different Madison. In the original Notes, Madison was annoyed and frustrated. Slowly by altering a word here, a phrase there, he became a moderate, dispassionate observer and intellectual founder of the Constitution.

Madison understood his revisions as repeated efforts to create a record—his record—of what he saw as significant in the Convention. Yet each revision increased the distance from the summer of 1787. Over the years, words, concepts, compromises shifted focus and took on new political meanings. Motivations were disputed; context lost. The Convention could not see the Constitution until the final days. And from the moment the Constitution became visible, it was contested. The respect owed the framing generation demands appreciation for the political world in which they struggled to stabilize the country. Over the first decade, the Constitution survived and indeed began to become the Constitution.

Madison’s narrative was always that of James Madison, a member. Continuing for a half century after 1787, he struggled to understand what had happened that summer.

The first original sentence read “Monday May 14 was the day fixed for the meeting of the deputies in Convention for revising the federal Constitution.” Madison eventually deleted the word “Constitution” and replaced it with “system of Government.” The revised sentence unambiguously declared the transformation of a federal system of government to a federal Constitution. Over the half century, Madison left one word unchanged. He never altered the word, “revising.” To Madison, revising was an essential element of American constitutionalism.

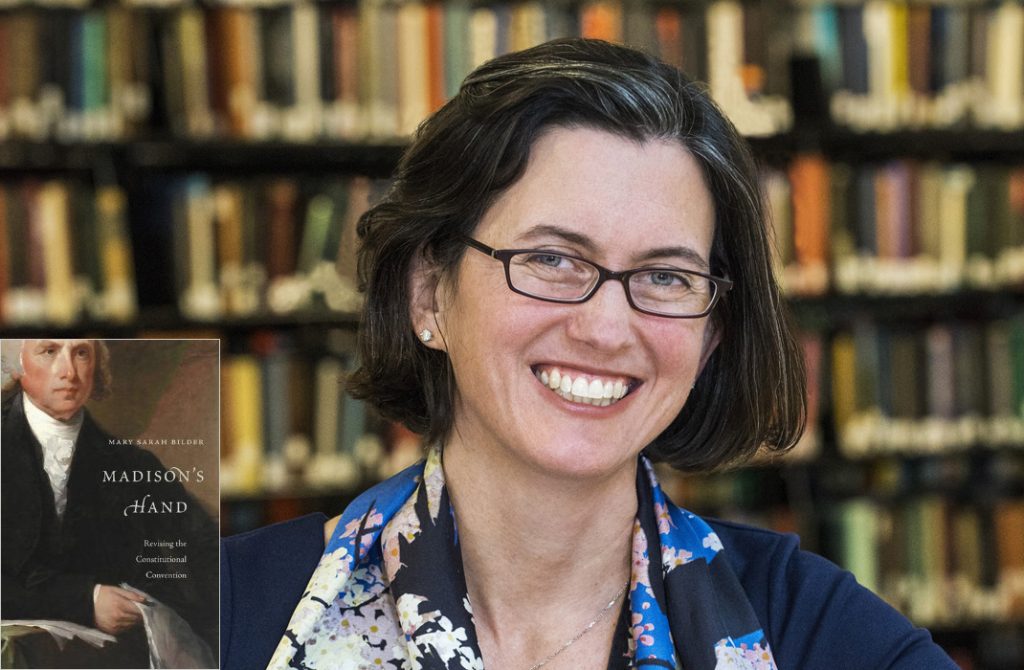

Mary Sarah Bilder is Professor of Law and the Lee Distinguished Scholar, Boston College Law School, and author of Madison’s Hand: Revising the Constitutional Convention (Harvard University Press, 2015). This op ed was originally published online by the History News Network.