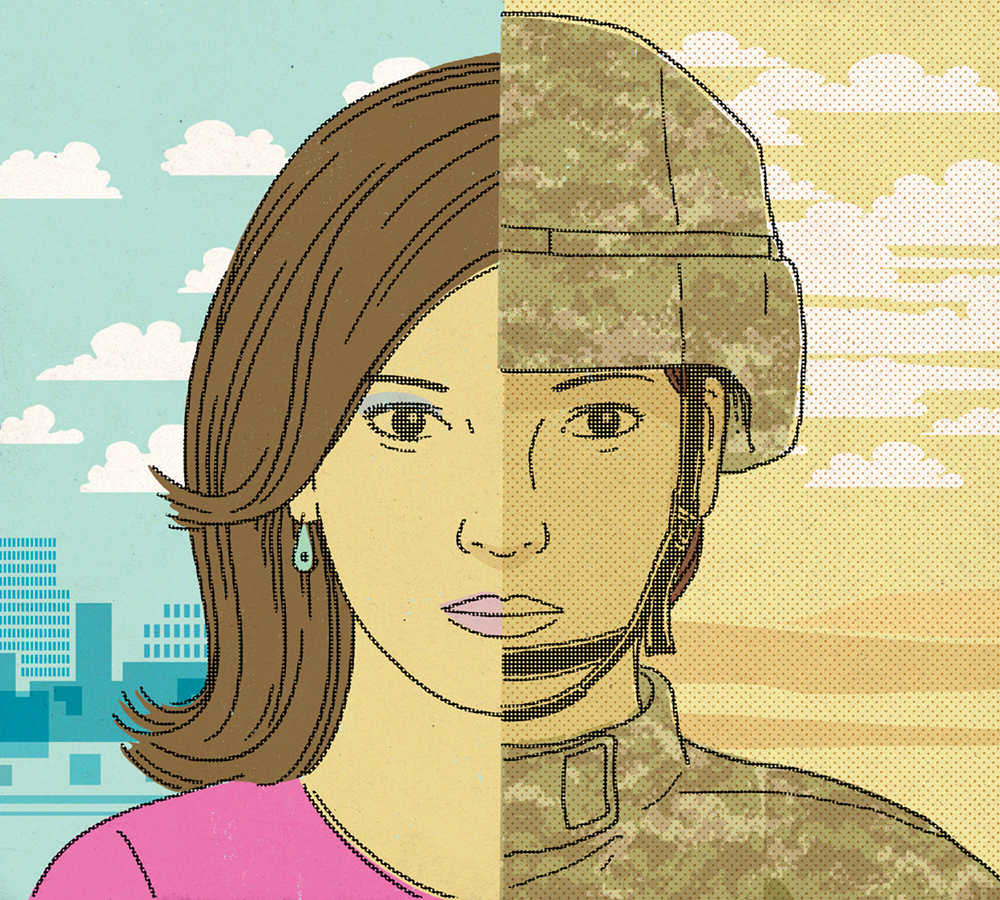

Secretary of Defense Ashton Carter has determined that combat positions will be open to women beginning this January. It is the right decision for the armed services and the nation. It is also a courageous one because it rejects a Marine Corps recommendation that infantry and force-reconnaissance units remain male-only. Navy Secretary Ray Mabus publicly rejected the Marines’ position and set the stage for Secretary Carter’s decision. The secretaries’ actions are worth studying and praising at law schools to develop leaders and promote social justice.

As the propriety and challenges of the momentous change are debated, I encourage a focus on citizenship and gender equality. Regarding the former, I think of George Washington’s 1775 letter to the New York legislature: “When we assumed the Soldier, we did not lay aside the Citizen.” Washington offered this as assurance that he would return to civilian life after the Revolutionary War. I suggest two contemporary meanings of this poetic statement.

The first is that military leaders must view their stations as temporary, incomplete departures from civilian life. Service members are charged to approach their responsibilities on behalf of a nation, not just a branch of service, military unit, political party, or ideology. This can be daunting. Individuals and organizations operate with and develop biases and flaws; however, great leadership enabled the Army, Navy, and Air Force to recommend that women serve in infantry, special forces, and other combat positions.

The second is that the opportunities of citizenship must be available to all. To exclude women from combat roles is to deny them the opportunity to give full expression to their understanding of citizenship. It also limits their opportunity to be role models, and perhaps even tomorrow’s citizen-soldier-stateswomen par excellence.

Regarding gender equality, I think immediately of a former student. She volunteered to serve fellow veterans through a disability clinic. A discussion with veterans in another public service program quickly revealed that one’s era of service, combat status, and gender create a pernicious hierarchy. It occurred to me that my great professional mentors—former judges, a US Senator, a dean—provided better examples of character, leadership, justice, and public service. They all happen to have served in combat positions. There are no equivalent female role models for my student to emulate, but they should abound for the next generation.

My student’s experience demonstrates how organizational values and culture shape personal views. West Point and the Army Military Police Corps exposed me to (comparatively) extraordinary gender diversity during my military service. My classmates, commander, machine-gunners, and patrol officers were women. Photos of female generals dating to the 1970s hang in the Military Police museum for all to regard. Female Military Police soldiers have seen combat since 1983 in Grenada and earned awards for combat valor since Panama in 1989. In recent months three women graduated from the Army’s Ranger School. Two are West Point graduates; one of these is a Military Police officer. I feel a deep kinship with these comrades-in-arms particularly because West Point and the Military Police Corps have enabled it in me. The best academic and professional institutions will do the same.

Law schools already seek diverse faculty and student populations to create ideal learning environments. Teaching leadership throughout the curriculum can further improve a law school’s culture. It would be particularly fitting for BC Law to invite Secretary Carter or Mabus to campus to recognize that their leadership embodies the highest ideals of the legal profession: to work toward a more just society.

David Delaney ’03, who teaches at Indiana University’s Maurer School of Law, was the founding president of the BC Law School Veterans Association.