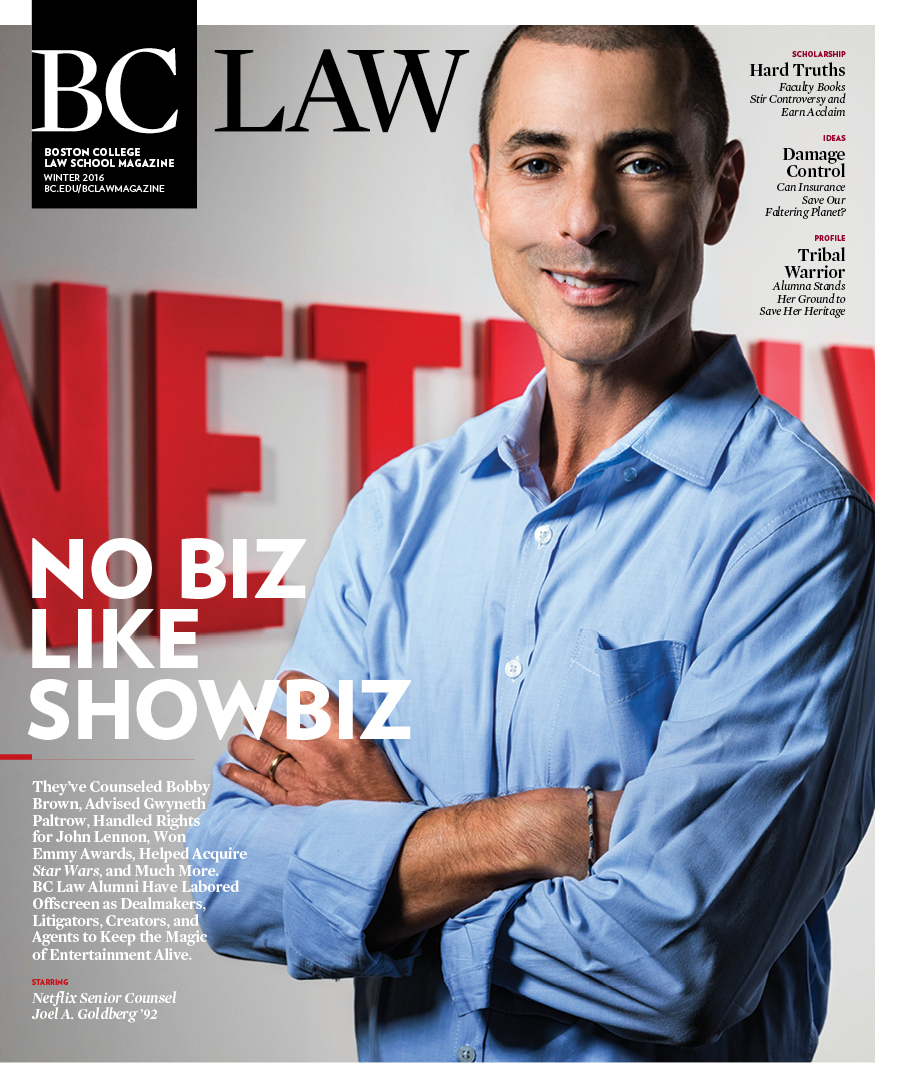

A few weeks before the Berlin Wall crumbled almost three decades ago to break up the Cold War, Joel Goldberg grabbed a seat in property law for the first time. Nine jobs and untold pay grades later, the fifty-three-year-old Netflix senior counsel still invokes his old professor, Zygmunt J.B. Plater, every time he wades into a deal. It seems Professor Plater—still teaching at BC Law long after borders and maps were reshaped by German re-unification—admonished his students to always walk the land” in every transaction.

Unprompted, Goldberg calls Plater’s counsel “excellent advice in all manner of deal-making” and adds that he “couldn’t be happier” having chosen BC. Goldberg’s classroom takeaway is especially apt, given that he now works within a wildly innovative corporate culture operating at light speed, which often looks as it leaps, rather than before. Walking the land of the deals he’s doing these days is as much about navigating unmapped territory as it is about building bridges.

“This is the most dynamic company I’ve ever worked for,” says Goldberg, who’s made his living in interactive entertainment, traditional television, and the studio business since coming to LA in 1997. “The priorities of six months ago feel so long ago because the business is evolving and we reorganize so quickly. At other companies, ‘reorganize’ is often a buzzword for getting rid of people. That’s not the case here. We’re in total growth mode. We’re quite willing to blow up how we do business on a semi-regular basis when we think there’s a better way to do it.”

So far, so good.

The world’s leading internet television network and largest video streaming on-demand service, Netflix is challenging convention, confounding traditional media, and expanding more swiftly than Imperial Rome. Already the largest driver of peak downstream internet bandwidth in North America, the network boasts more than 40 million domestic streaming subscriptions, claimed 14 Emmy nominations in 2015, and earned eight such nods for January’s Golden Globe Awards. HBO received seven Globe nominations. Amazon five.

Internationally, Netflix now operates in a whopping 130 countries, which is double its penetration at the close of 2015, and is available in 21 languages. The entertainment juggernaut began this year serving a streaming—or, “over-the-top” in industry speak—membership of more than 70 million worldwide. Subscribers watched 12 billion hours of Netflix programming in last year’s fourth quarter, a jump of almost 50 percent from 2014. What’s more, an OTT deal with China appears to be in the on-deck circle.

Goldberg’s individual responsibilities are uncommonly broad and fast-paced, even in the context of entertainment law. That, too, is notable given that the business typically runs the gamut. Building and protecting a brand is ground zero. But many entertainment lawyers find themselves toiling within a Venn diagram of common elements. They include intellectual property, contracts, torts, trademarks, copyright, labor, advertising, First and Fourth Amendment constitutional law, bankruptcy, insurance, licensing, advertising, and product placement along with statutory tax and criminal law. Goldberg’s day-to-day can touch all of that, and Netflix’s globe-trotting ambitions mean that no two days are alike, forcing a lot of the lawyering to take place in a no-huddle offense.

He leans heavily upon his diverse résumé to keep pace.

Goldberg’s first half-decade out of law school was split between IP litigation and advertising law before he landed in California as a director of business and legal affairs handling internet and e-commerce activities at Universal Studies. By 2002, he was at CBS Interactive negotiating talent, licensing, distribution, and production agreements until spending two years there as a biz-ops vice president beginning in 2006. He honed his original content development and production acumen, including mobile, via VP posts at MySpace and then in traditional television upon his return to CBS in 2011.

Goldberg came to Netflix in 2013 and handles global content licensing (right-to-air agreements) for foreign television, children’s programming and independent studios, including indie films. Legal nuances gleaned at each of his previous stops come into play almost every day.

“I’m in a very fortunate spot to oversee a broad portfolio of programming, so even going back to my advertising or social media days, all of these issues arise,” he explains. “Even if the bulk of what we’re doing is licensing programming, there are marketing issues that come up—both in what we want to do and what we leave for our suppliers to do. For example, if each of us wants to run a social media campaign around programming, all of these issues around advertising and marketing emerge.

“From the litigation standpoint, every deal involves risk-assessment,” he adds. “And you are so much better at that if you’ve seen how deals have gone bad, where they go bad and where they don’t. Freedom of responsibility is part of the culture at Netflix. If you’re here, you’re considered an expert in what you’re doing and there’s a lot of trust that you will apply that expertise toward the greater context of the overall organizational goals.”

Steering clear of a silo mentality is praiseworthy, to be sure. But the approach is by no means a cutting-edge business objective across American corporate culture. The difference, says Goldberg, is that at Netflix, cross-disciplinary input and impact aren’t merely encouraged. They’re expected.

“It’s by far the most transparent place I’ve ever worked and it does a tremendous job of sharing information internally, in context,” he explains. “In other words, ‘this is what we’re trying to accomplish’ and each of us has our role within that—marketing, legal, finance, whatever. With greater context for what the company is trying to achieve, you can understand how your piece fits into that. Then it’s your job to work within that framework and ask questions when you need to.”

It’s hard to argue with the results. Netflix is on a remarkable run. Trading on the NASDAQ Composite Index as NFLX, the company’s stock is up 350 percent since 2010. Its original series House of Cards hauled in better than $100 million in sponsored ads in its inaugural season of 2013. Today, more than 60 percent of US households can stream Netflix via their TV, a phenomenon that’s eviscerating cable subscriptions nationwide.

Smartest Guys in the Room

Netflix owes much of its success to innovation and intestinal fortitude. The Los Gatos-based firm has disoriented competitors and would-be advertisers alike with bold and brilliant tactics. Whether creating critically acclaimed (and pricey) original programming or resurrecting a defunct show with a cult-like following (see: Arrested Development) or alienating theater owners nationwide with the simultaneous, same-day release of a feature film (Beasts of No Nation) on the big screen as well as via subscription streaming service, Netflix has made a habit of upsetting the apple cart.

Recently, the company tried shifting the paradigm again when it signed on to be the platform for the independently produced series Back Stabber, whose makers offered the lowest ad rate spot in Netflix history. The show’s costs for product placement were calculated at about 1/1000th of the typical cost per viewer, and its producer refused to accept advertising from large corporations in an effort to stimulate localized small businesses.

“We’re a very risk-tolerant company, and that [mentality] flows from the top down overall, and from the top down within the legal department,” says Goldberg. “It’s an incredibly liberating way to work. We look at a big part of our job as risk-assessment and the responsibility to explain that risk to the other folks who are impacted. Netflix looks at risk as something that must be understood and embraced and something you’re willing to take on to push the envelope and improve the service.”

Both in form and function, Netflix is a disruptive industry force. Goldberg suspects it’s kept him from becoming set in his ways. Despite the fact he graduated college back when desktop computers looked like Samsonite luggage.

“I’m not necessarily a first-adopter or a huge user of new technology,” he admits. “What I do love is being put into a situation where something new has come along and I need to understand it and how it impacts our business. How it impacts the rights flow, how we’re dividing things up, how the technology works from a distribution perspective and how content is protected in this new form of distribution—be it mobile or streaming over multiple devices.

“I have to do that internal research,” he continues. “I have to reach out to the product people or the engineering people and say, ‘OK, treat me like a Luddite, walk me through this, help me understand how this tech works and where it’s going to go.’ It requires a lot of outside reading and I’m on Wikipedia every time a new acronym comes along. That’s the stuff that keeps my spirit young in these very young businesses.”

While Netflix’s Midas touch and Generation Z ethos don’t extend to every venture (the Back Stabber release date was pushed back this past fall as its cash-poor producers considered a move to network TV), some of Hollywood’s brightest stars have bought into its model, including some A-list standard-bearers.

In his keynote speech at the 2013 Edinburgh International TV Festival, two-time Oscar winner Kevin Spacey proclaimed, “Clearly, the success of the Netflix model … proves one thing: The audience wants the control. They want the freedom. For kids growing up now, there’s no difference watching Avatar on an iPad or watching YouTube on a TV or watching Game of Thrones on a computer. It’s all content. It’s all story.”

To his credit, Goldberg echoes the sentiment with equal eloquence, and takes it a step further.

“This is a generation that knows it can get what it wants when it wants it, and it gets very frustrated when it can’t,” he says. “People our age can’t always find what they want, so they’ll find it when they can, or they’ll still click on the TV and flip through the channels. I think that’s a behavior that’s dying and this next generation—starting very young—is used to picking up something, touching it, finding it, getting it, and watching it over and over again. More so in the kids space than anywhere else, interactivity is in their DNA, so we are pushing to own that audience.”

The world’s leading internet television network and largest video streaming on-demand service, Netflix is challenging convention, confounding traditional media, and expanding more swiftly than Imperial Rome.

It’s an audience that’s growing. In a recent survey by IBM subsidiary Clearleap, more than 7 in 10 adults reported they’ve used a streaming service, while 26 percent of Millennials surveyed had never subscribed to pay TV. This singularly plug-and-play demographic is poised to explode, and Netflix knows that kind of volume will require infrastructure. Accordingly, it will feature 31 original scripted series in 2016, nearly doubling its 2015 total of 16. The company also has 10 feature films in various stages of production. Netflix plans to be present in every country by the close of 2016.

One of Goldberg’s casual asides offers a case study of the company’s free-spirited dynamism.

In preparation for its 2014 service launch in France, so the story goes, the company took a stab at teaming with a local, French production company to commission a show shot and produced in France, in French. While that script was still in production, the idea gained remarkable momentum.

“We’re having success with big, original series in the US, so pretty soon we thought: ‘Why not elsewhere?’ We went out and signed deals for similar programming in Mexico and Brazil and now we’re looking at local markets all around the world. The first of these products to air (Mexico’s Club de Cuervos chronicling a dysfunctional family that owns a club soccer team) has been incredibly successful.”

Almost overnight, Netflix carved out a new division dedicated to creating local, original programs—a group that now rolls up to Goldberg on the legal side. A ”what if?” became a huge strategic imperative for the company in the course of a calendar year.

At the end of the day, it is Netflix’s multi-national proliferation and broad demographic appeal that has traditional media shaking in its boots. This past summer, Disney CEO Bob Iger attributed a dip in ESPN viewership to “the rapidly changing media landscape” and acknowledged that younger viewers were increasingly drawn to streaming content. Within a month of the remark, more than $50 billion in market capitalization evaporated via declines in the share prices of Disney, AMC, CBS, Comcast, Discovery, Time-Warner, 21st Century Fox, and Viacom stock.

Goldberg is at the vanguard of this Netflix 2.0 blitz. He toils in two mission-critical arenas for the brand: children’s programming and foreign television. The former is potentially a golden goose, and sifting through line items in the corporate portfolio suggests as much. The company’s largest original content outlay to date was not for big-budget adult serials like House of Cards or Marco Polo,’ but rather for 300 hours of new DreamWorks Animation.

The reason? Children’s content is more evergreen, targets a profoundly less fragmented audience (Ibid., Bob Iger) and, DreamWorks notwithstanding, is typically cheaper to license.

“If a subscriber has children who watch things on Netflix, we’re never going to lose that subscriber; their kids won’t let them,” says Goldberg. “It’s a tremendous retention engine for us. We’ve been incredibly aggressive in creating a lot of original, new children’s properties for Netflix. It doesn’t get quite the attention of an Orange Is The New Black, but we’re working with production companies all over the world—Australia, UK, Canada—to bring new intellectual property in the form of series to premiere on Netflix. In the past, the only outlet for those things would have been linear television.”

Since his sixteen-year-old daughter, Julia, isn’t watching much animation these days, Goldberg is probably off the hook when he characterizes foreign markets (as opposed to How to Train Your Dragon 2) as “the fun part of the business.” What’s more, it is inside the statutory rabbit warren of international television where Goldberg earns his keep.

“Each country has different legal quirks and requires a fair amount of legal research,” he explains. “We work with local counsel to understand what issues we’re facing, and we’ve done enough of these territorial launches that we have a good set of questions to ask. Still, every market presents surprises and challenges. We go in knowing that we’re going to face issues that we didn’t necessarily contemplate and that we’ll deal with them and they won’t slow us down.”

While that may sound awfully intrepid, perhaps it’s a sign that the man and the multinational are actually cut from the same cloth.

“I don’t know about that, but in my view, there’s nothing more organic than this Netflix experience,” Goldberg says. “Within one interface and one product, we have programming across the spectrum. When a viewer ages out of watching their preschool show, we’re able to expose them to what might be the next-most appropriate thing and carry them into our tween programming, teen programming, and all the way up to adulthood. Obviously, we haven’t been around long enough to completely see that, but we are capturing families by offering them a product that’s taking them through their whole life cycle.”