It is hard to imagine crimes more devastating to the public than terrorist acts. The immediate victims, by design, are innocent bystanders who include children, the elderly, and others who are simply chosen at random. As those who live in Boston know all too well, the harm is not confined to the initial crime scene: The lasting impact is felt by all in public spaces and at public celebrations for years after the event.

I do not want to minimize the inhumanity driving these crimes or the depravity motivating the terrorists who engage in such misguided attacks.

But, from my experience in the defense bar, my primary concern is that the threat of terrorist attacks is expanding law enforcement powers—powers that, if not kept in check, imperil important civil liberties.

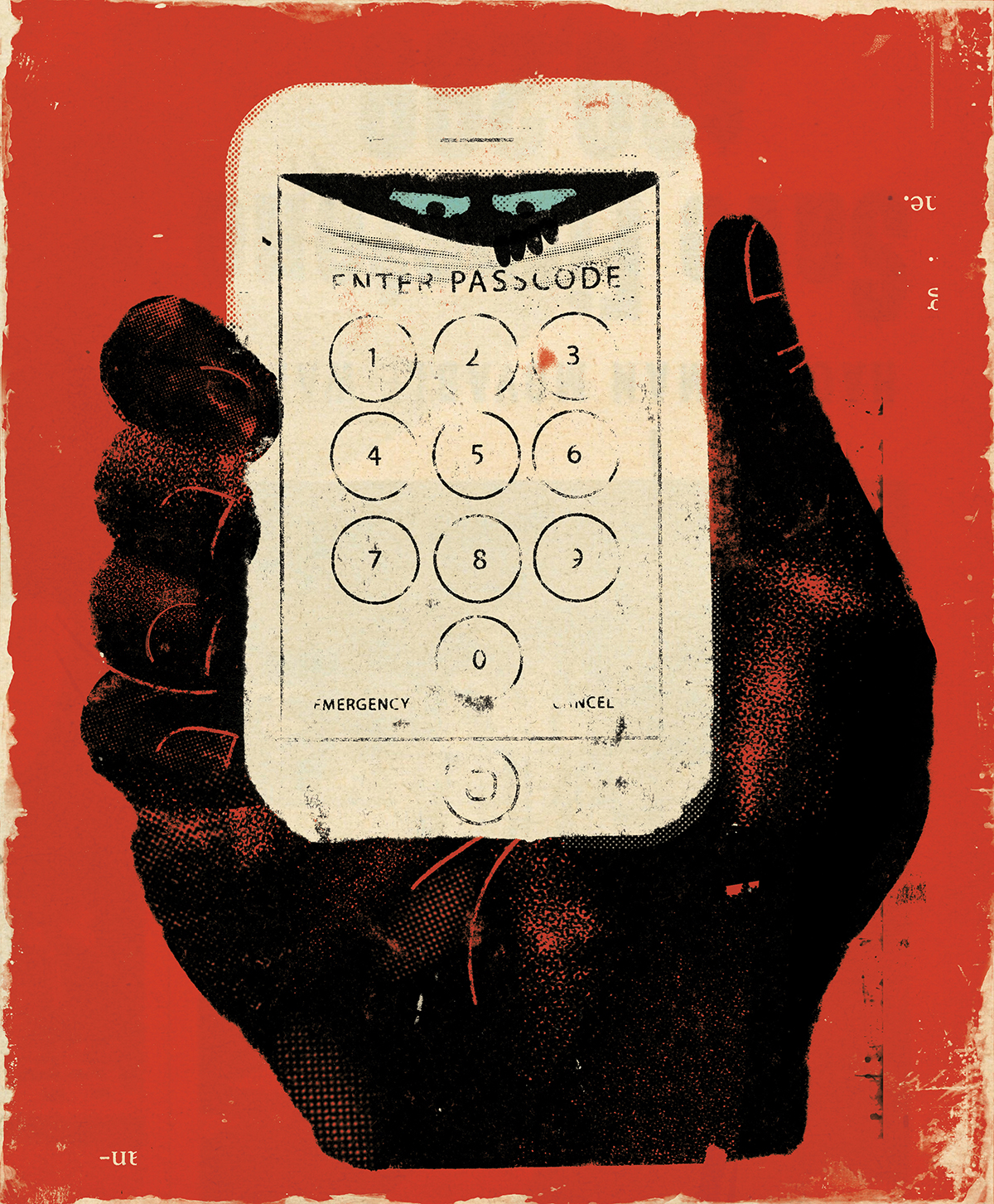

One recent example of excessive might was the recent iPhone lawsuit by the FBI. Shortly after the Decem-ber San Bernardino terrorist attack, the FBI sought a court order to compel Apple to rewrite its operating system and permit the FBI to hack into one of the attackers’ phones. The government—in the courts and in the public sphere—framed this request as a matter of national security.

In reality, as it was quickly revealed, the FBI had similar requests in nine other cases, none of them concerning national security. One, in fact, involved a New York drug dealer whose iPhone the FBI wanted to hack simply to identify his customers.

Another startling example was the show of force by militarized police in Ferguson, Missouri, in response to unrest after a black teenager was shot by a white officer in 2014. The police hit the streets with armored tanks, gas masks, and assault rifles, equipment police forces nationwide had begun acquiring after Congress authorized the buildup in 1997 to protect citizens from terrorism. The scene in Ferguson, a sight usually reserved for military coups in Third World countries, was so unsettling that the call to curtail the militarization of police forces ensued.

My secondary worry is that the urgent and ratcheted calls to prevent terrorism are not keeping the threat in perspective. The actual fatalities from terrorism are low. Between 2001 and 2013, in the United States, 3,380 people were killed in terrorist attacks and 406,496 were killed by gun violence. Starting at 2002 (to take out 9/11), the numbers are 390 to 376,923. Put another way, since 2002, toddlers with access to guns have killed more Americans than have terrorists.

In thinking about terrorism, then, my call is to carefully consider the costs of expanded law enforcement initiatives. Not all societies respond with a loss of civil liberties. In 2012, Norway experienced its most brutal act of terrorism, a deranged extremist who massacred seventy-seven people (mostly teenagers). Two days after the tragedy, Prime Minister Jens Stoltenberg, in an address to his nation, rejected a call for vengeance. He spoke in favor of freedom, not in acquiescence to aggression: “Our response is more democracy, more openness, and more humanity,” he said. “We will answer hatred with love.”

Likewise, the toughest response to terrorism is not always the smartest. As a criticism of the torture used in Guantanamo Bay, retired WWII military interrogators remarked that they had been able to successfully obtain information from Nazi captives in games of chess and ping pong. Benjamin Franklin once observed that “those who surrender liberty for security will not have, nor do they deserve, either one.” To avoid Franklin’s prophecy, my hope is that anti-terrorism measures remain targeted and proportionate.

Assistant Professor Kari Hong is an expert in criminal law and founder of BC Law’s BC Ninth Circuit Appellate Program.