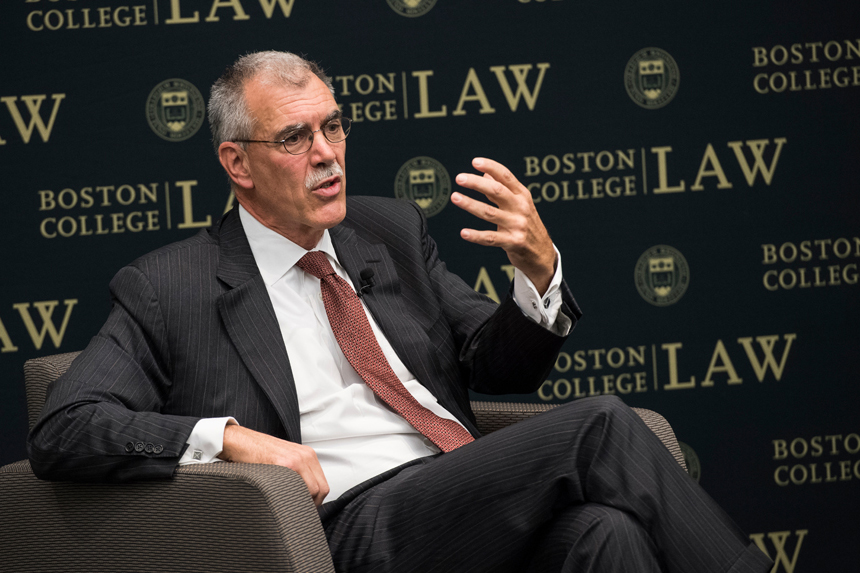

Litigating before the Supreme Court in a time of transition and discerning what the current climate of political division means for the future of the Court and the nation’s legal culture were key themes of a Conversations@BC Law discussion Oct. 18 between former US Solicitor General Donald Verrilli and Professor Kent Greenfield (watch the video below).

After a career both in and out of public service, Verrilli replaced Elena Kagan as Solicitor General when she joined the Supreme Court in 2011. He argued 37 cases during his tenure, including groundbreaking cases on same-sex marriage, affirmative action, and the Affordable Care Act.

Visiting BC Law as a Distinguished Lecturer of the Rappaport Center for Law and Public Policy, Verrilli explained that the Solicitor General’s office encompasses far more than legal representation of the US before the Supreme Court, the role most commonly known to the public. The Solicitor General interacts with the Justice Department and the federal government in a variety of ways, he said, offering a brief history lesson on the subject.

“Before the office was founded in 1870, right after the Civil War, the government would hire private counsel to represent the government, especially in Supreme Court cases…which led to an inconsistency in the government’s stances on many issues,” he explained.

The Solicitor General’s Office was thus formed both to make the legal representation of the US government a civil service position, and to explain the government’s position on a variety of legal issues. Verrilli said that can be very difficult because of longstanding and deep conflicts built into the executive branch that lead different parts of that branch to want the government to take different positions. “It’s up to the Solicitor General to gather input from many sources and ultimately decide what position the government should take.”

Verrilli served as Solicitor General from June 2011 to June 2016, a period that included the passing last February of Justice Antonin Scalia. “His death created a vacuum…as his questioning in oral argument was very intense. When you subtract all that from the equation…there was just a yawning gap in the court” for everyone else to fill during oral argument, Verrilli said, including junior justices Sonia Sotomayor and Elena Kagan.

Verrilli expressed concern that the politicization of the nomination process of Merrick Garland to fill Scalia’s seat could send a signal that all that really matters in the selection of a Supreme Court justice is how a nominee is going to vote when deciding cases. “The extreme level of attention to political matters threatens to debase the credibility and esteem in which the Court is held by the American people,” Verrilli cautioned.

Verrilli provided his perspective on some of the more important cases he argued before the Court. They included National Federation of Independent Business v. Sebelius (the first and principal Obamacare case), United States v. Texas (the recent immigration case), and Obergefell v. Hodges (the marriage equality case).

When faced with cases of particular moral urgency, Verrilli said, he placed special importance on transcending specific legal issues to achieve a higher consideration of the right position for the government to take.

An example was the time, as he prepared for Obergefell v. Hodges, that Verrilli felt compelled to speak to President Obama directly.

Uncertain of the strength of the government’s arguments for involvement, Verrilli scheduled a meeting with the President, which, to his surprise, lasted for 70 to 75 minutes. “It was an incredible experience and discussion,” he said. “[The President] knew there was a meeting about legal issues but not what the issues were specifically concerning.” So Verrilli found Obama’s responses even more impressive. The President, he said, immediately grasped the issues and slipped into the moot court mode of a constitutional law professor, peppering him with hypothetical questions from various justices.

Verrilli then referenced Martin Luther King Jr.’s “Letter from a Birmingham Jail,” which argues against waiting for justice. He had read it the evening before as he cast around for an answer as to whether the government should act on the case then or wait. Obama, of course, knew King’s “Letter.”

“Both of us came to the same conclusion that this was a question that ‘could not wait,’ for doing so would split the country into two nations,” Verrilli said. “And while the President asked for time to consider, a few days later I was given the directive to file for the government.”

The rest is history.

Photograph by Catherine Wechsler, MTS, BC