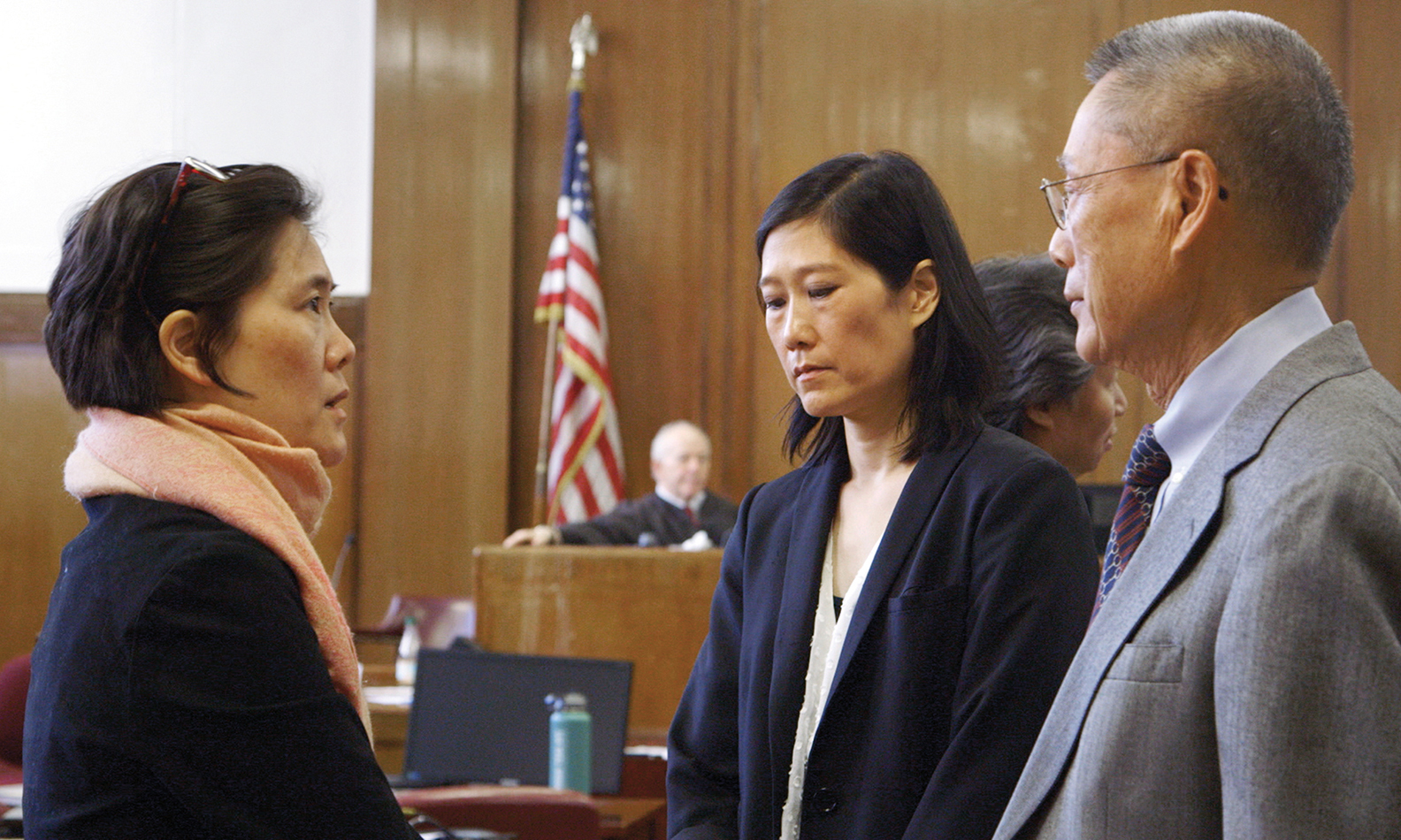

Fifteen Chinese-Americans were handcuffed, chained together, and paraded by law enforcement down the narrow hallway of a New York City courthouse. Cameras flashed as they held on to each other, hunched over, trying to cover their faces. The date was May 31, 2012.

At a splashy press conference, Manhattan District Attorney Cyrus Vance Jr. announced the indictment of Abacus Federal Savings Bank plus nineteen of its former employees, including the head of the loan department. The charges: 184 counts of falsifying business records, and of residential mortgage fraud, grand larceny, and conspiracy. The indictment claimed that the bank had falsified loan applications so that unqualified borrowers could obtain home mortgages, and then sold these fraudulent mortgages to the Federal National Mortgage Association—Fannie Mae—the alleged victim. Invoking the 2008 mortgage debacle, DA Vance said, “If we’ve learned anything, it’s that at some point, these schemes unravel and taxpayers are left holding the bag.”

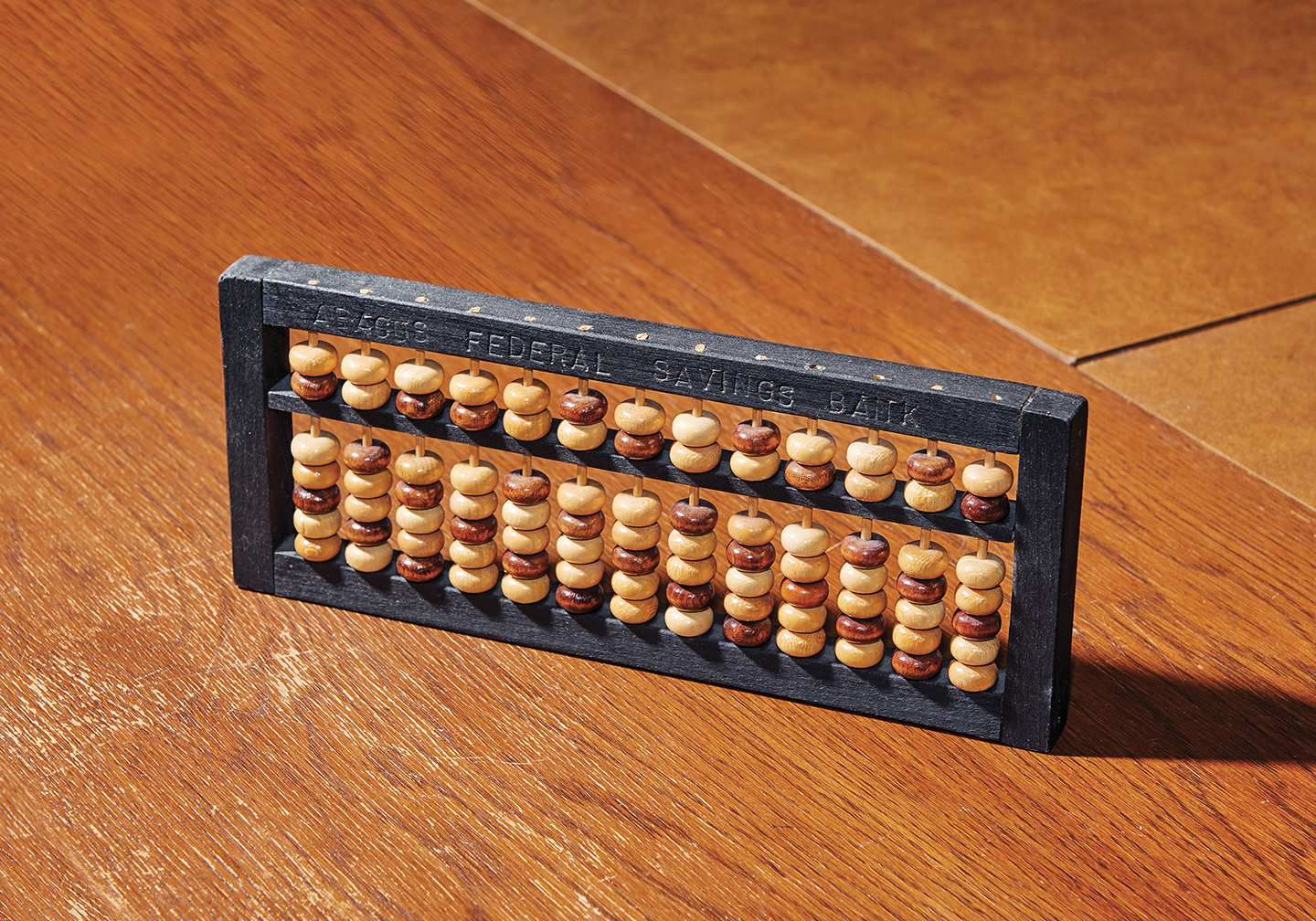

Abacus, which was founded by the father of Vera Sung ’90 and Chanterelle Sung ’04, was, and remains, the only bank indicted in the wake of the 2008 financial crisis. The case is the subject of the PBS documentary Abacus: Small Enough to Jail that has been nominated for an Acacemy Award. More than that, the story of Abacus and the Manhattan DA’s office is a cautionary tale of what can happen when a culturally distinct community of immigrants seeks to share in the American dream, and a zealous prosecutor’s office concludes that its efforts to do so are criminal.

In the dizzy years before the great depression of 2008, lenders were pumping up a speculative housing bubble and getting very, very rich by predatorily throwing mortgages at homebuyers with poor credit ratings. These subprime mortgages were pooled together into securities and sold as investments. Lured by the rising values of their rapidly appreciating homes, homeowners went on a consumer spending spree. The US economy was booming.

Few people questioned whether any of this was wise. A notable exception was the founder and chairman of Abacus Bank, Thomas Sung.

Thomas could have jumped on the bandwagon. In 2006, a broker from Chicago had tried to sell him highly rated mortgage-backed securities boasting a 12 percent yield. Thomas requested more information. Days later, a large binder reached his desk, filled with pages of impenetrable fine print. In a follow-up conversation, Thomas asked the broker what happens if the loans behind the securities defaulted. Oh, not to worry, he was told. There hasn’t been a default in seven years.

“I go back a lot longer than seven years,” Thomas told him, “and I have seen defaults where home prices drop by as much as 35 percent. I do not think that these are sound securities.”

And that was that. Abacus never invested in mortgage-backed securities, nor did it ever originate any subprime mortgages. When the housing bubble burst, the world tumbled into financial crisis. Millions lost their homes, their savings, their livelihoods. But Thomas Sung’s hands were clean.

Abacus continued about its business. Then, something happened. In December of 2009, Thomas’ daughter Vera, a member of the bank’s board of directors, and her sister Jill, the bank’s president and CEO, discovered that, in an otherwise routine home mortgage closing, a low-level employee was embezzling funds. They stopped the closing. They fired the employee. They reported the incident to the bank’s compliance officer. They hired an outside consultant to investigate, which resulted in more firings and several resignations. They notified their mortgage financer Fannie Mae. And they advised the borrowers to report the matter to the police.

“This was exemplary conduct,” says BC Law Professor Patricia McCoy, an expert in banking and banking regulation. “Any bank has a risk that a rogue employee or two will engage in fraud.” Getting to the bottom of why the fraud happened and preventing it in the future was a job for the bank regulators.

But Manhattan DA Vance didn’t see it that way. His office started investigating. Abacus officials fully cooperated, ultimately handing over to the DA more than 600,000 pages of neatly organized documents. But as the DA’s questioning grew increasingly hostile, it dawned on the Sungs: They aren’t just investigating this small matter. They are investigating us.

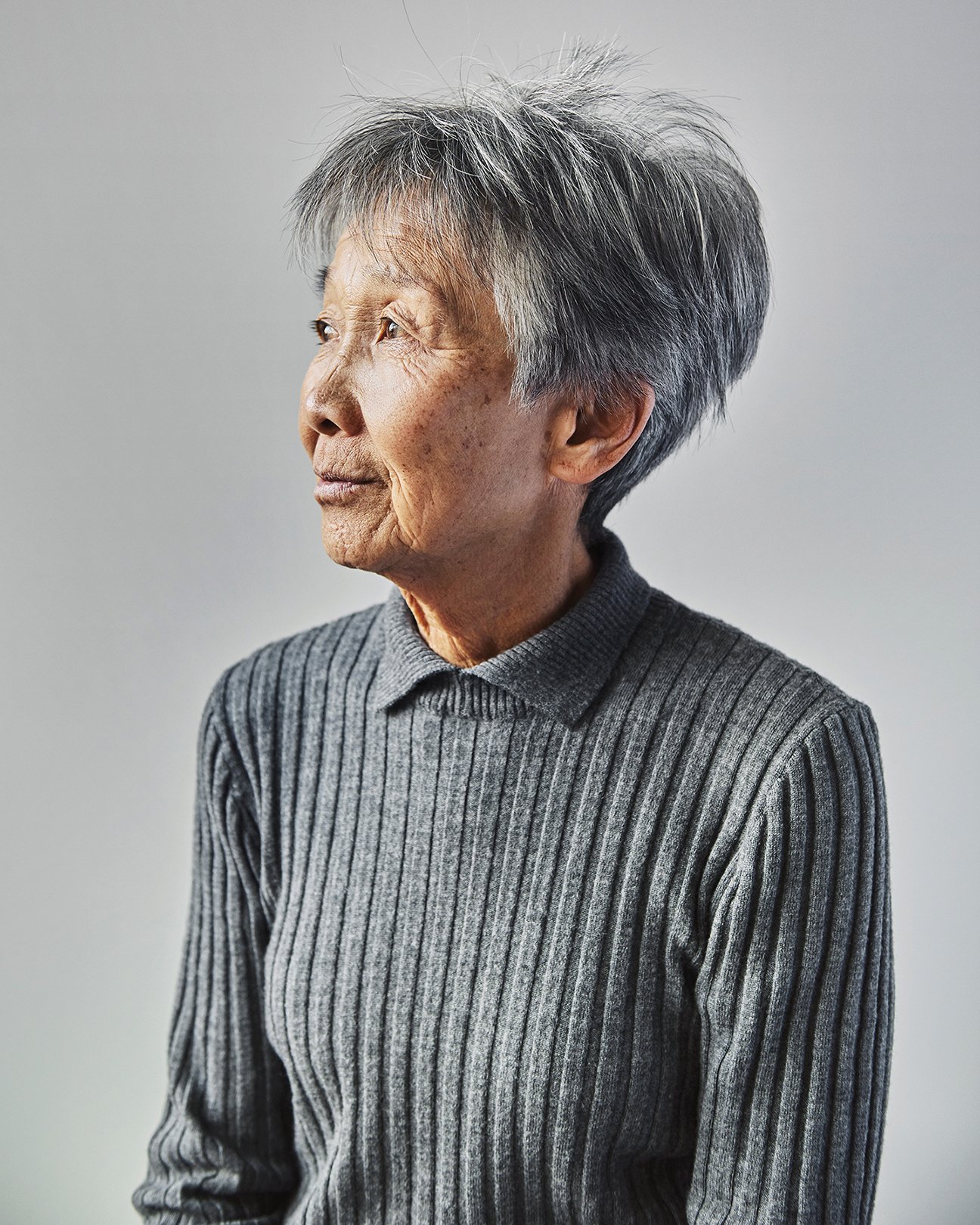

To Thomas, Abacus was more than just a bank. It was a community service. Born in Shanghai, Thomas was sixteen when he immigrated to America with his mother and father in 1951. Hardship struck when his mother passed away. Thomas pursued his education while helping the family and holding down a job, eventually graduating from Brooklyn Law School. He met and married Hwei Lin Tseng in the early 1960s, became a leader in Chinatown’s community associations, and ran his own law firm while Hwei Lin stayed home with their four daughters, Vera, Jill, Heather, and Chanterelle. He helped his clients obtain citizenship, open businesses, buy homes. He noticed that, while the “mainstream” banks were happy to accept deposits from their Chinese patrons, they were less enthusiastic about lending them money. Abacus Bank was born of Thomas’ insight that if the people of Chinatown were going to partake of the American dream, they were going to need capital.

“When you think about corruption—people cut corners and they try to find an easy way out. That is so counter to how we were raised…to not be afraid of really doing things the hard way. The right way is harder.” —Chanterelle Sung

The Sungs’ realization that the DA’s office was turning on them came with an added jolt: Chanterelle was an assistant DA working in the very same division that was investigating the bank. “I had always wanted to work in the public service and that’s something I did for eleven years after graduating from law school,” Chanterelle says. Seven of those years she spent with the Manhattan DA. Chanterelle’s earliest memory of doing public service was when she was a young schoolgirl and volunteered for the Red Cross. “My mother wanted to make sure that I was using my time wisely, that I wasn’t going to be just wasting my summer away. She always said you have to be doing something good,” she added.

“My family was very respectful of the fact that I actually had a great career at the DA’s office and enjoyed it tremendously,” Chanterelle says. “They kept me firewalled from what was going on in terms of the case against our bank. The office requested that as well so that there wouldn’t be a conflict of interest.” But Chanterelle ultimately left the job she loved to be with her family in the fight of their lives. “I wanted to be able to know everything that was going on and I really didn’t have that ability by staying in the office,” she says.

During the period covered in the indictment—2005 through 2010—the bank’s loan-default rate was less than half a percent. That’s extraordinarily low—the national average was more than 5 percent. Fannie Mae, the alleged victim, had profited by more than $100 million from loans originated by Abacus. Abacus was the 2,651st largest bank in the US, with just $300 million in assets, and had never trafficked in the questionable mortgages that had brought down the US and world economies. In contrast, the too-big-to-fail institutions like Morgan Stanley, Goldman Sachs, JP Morgan, Chase, and Citicorp had issued $4.8 trillion in fraudulent mortgages and had received a $700 billion government bailout, paid $110 billion in fines, and were given deferred prosecution and non-prosecution agreements. The only offer Abacus got was to plead guilty to a felony and pay a $6 million fine. That disparate treatment “was something that was so upsetting for us,” says Chanterelle.

The Sungs, none of whom were ever indicted by the DA, did not believe that the bank’s actions amounted to criminality. The bank’s clientele operated in a largely cash economy and did not always have the W-2 forms, tax returns, and other documents that were the standard for establishing a borrower’s good credit. Over many long years, Thomas had worked with Fannie Mae to find other ways for the bank to document the credit-worthiness of its prospective borrowers. “My father asked Fannie Mae if borrowers could submit their telephone bills, other utility bills, and rent payments if they did not have traditional credit records,” says Vera. “We continued to work with Fannie Mae to ensure that qualified borrowers could document their credit-worthiness in a way that would meet Fannie Mae guidelines. Fannie Mae was always very accommodating and willing to work with us until they were placed into receivership by the federal government in late 2008.”

Pleading guilty would have meant the end of the bank. The Sungs decided to fight. “What choice did we have?” Vera says.

The trial opened on February 23, 2015. In the end, the jury would have to choose between two opposing stories. In the prosecution’s story, Abacus and its employees had criminally conspired to defraud Fannie Mae. The Sungs’ team of lawyers argued that there was no fraud, as evidenced by the fact that Fannie Mae had suffered no losses or harm.

“You have a criminal justice system that sits over a cultural community that it is not sensitive to and that it doesn’t recognize. The people who run that system must be willing to understand the community.” —Chanterelle Sung

The Sungs attended the trial every day, and did their best in the courtroom to hide their anguish. But they kept their wits about them: At one point, the prosecutors moved to introduce into evidence a set of guidelines from Fannie Mae. The problem was, these guidelines had come into effect after the financial crisis and did not apply to the period of the indictment. That was a pivotal point in the trial. “We had no idea that the grand jury indictment had been based on Fannie Mae guidelines that were not relevant or applicable to our case,” says Chanterelle. “When Jill realized what was happening in court, she jumped out of her seat and tapped our lawyer on the back and whispered to him, ‘Wait, wait, this is wrong!’ After a long side bar, the court took a recess and the prosecutors came back after the lunch break very flustered.”

Behind the scenes, the Sungs met frequently, patching one another in as necessary by conference call, to debrief about the trial and take comfort in one another. Thomas was the calm, steady fighter, strategic attorney, and savvy public relations manager. Chanterelle and Vera, his lawyer daughters, joined him in these tasks. Jill was a strong, effective compartmentalizer, running the bank and watching the trial while keeping at bay her fear that the DA’s office would have her arrested in front of her children. (This never happened). Daughter Heather, a palliative care physician, was a soothing presence in family discussions. Hwei Lin, their mother, was the worrier for them all. But she found her much-needed cause for hope in the presiding judge, Roger Hayes, who reminded her of her beloved grandfather, Tseng Sao Suen. Her grandfather had been a justice on Taiwan’s highest court. Hwei Lin had taught her daughters that even though he was very poor, he was known as an honorable man who had served his community with integrity.

This was just one of many family stories impressed upon the Sung sisters as they grew up, stories in which hardship and poverty were no match for acting honorably and with concern for others. “We heard about the awful conditions our parents faced growing up in China—the dirt floors and the toilets which were just holes in the ground, the way they would have to go to the bathroom in the middle of the night, scared that something would jump out of the hole,” Chanterelle says. “These are images in our minds of our parents coming from very little means, and working so hard to make ends meet.”

Thomas and Hwei Lin were conscientious mentors to their children. “Our parents spent so much time with us,” says Chanterelle. Chanterelle swam competitively in high school, and her mother drove her to and from swim practice every day. She loved this time alone with her mother.

Vera admits that “I would have loved to be hanging out at the mall with my friends, but our parents were very strict,” then quickly adds that her parents were not at all like the “Tiger Mother” stereotype. “It was more like, do the best you can, but be good,” she says. Vera helped her father in his law office, and accompanied him when he visited his properties. He also taught her how to use a hammer, a screwdriver, a drill. How to mix cement. He taught her how to write a check, and eventually, how to do closings, which she does to this day at his law firm Sung & Co., PC, where she is an associate.

When illness struck a neighbor, or a stray cat needed a home, Hwei Lin would always help. “That is my mother,” Vera says. Weekends were for chores, with both parents and all four children chipping in. There were no nannies, no maids.

In this way, the Sung sisters learned that hard work and virtue go together. “We never were told to short-cut things. Our parents always did things the hard way, from scratch. When you think about corruption—people cut corners and they try to find an easy way out. That is so counter to how we were raised,” Chanterelle says. “I think that has something to do with it—not being afraid of really doing things the hard way. The right way is harder.”

And for the Sungs, the trial was hard indeed. The adversarial system demanded that borrowers testify against bank employees, that employees testify against their supervisors, and that lawyers catch all of them in lies. Thomas worried that the reputation of the Chinese-American community was being sullied.

The response of the community was complex. People felt loyal to Abacus. The indictments had sparked no panic among depositors, perhaps because Thomas had made a preemptory statement to the Chinese press, telling the community that Abacus had cooperated with the DA and that the bank was not going to accept a guilty plea. On the other hand: “We had a lot of borrowers who ended up testifying against us,” Chanterelle says. “One of them, three weeks after testifying against us, came to the bank for another loan! It is like a pragmatic approach—the bank served them well, but they didn’t want to get into trouble by not cooperating with the prosecutors.”

As a purely legal matter, there was a central irony in the prosecution’s case. The DA claimed that the mortgage loans that Abacus sold to Fannie Mae were fraudulent because they were riddled with poor or improper documentation and hidden risks. But if Fannie Mae was the victim, the DA could not point to any tangible harm. During the time period of the indictment, Abacus sold 3,000 mortgages to Fannie Mae. Only nine had defaulted. As for the claims of fraudulent documentation, the defense introduced into evidence a 2012 email from Fannie Mae to Abacus which read, “We recognize that you have very unique needs that are closely linked to the borrowers you serve. While doing anything customized in this environment is very difficult, the team is committed to doing whatever we can to develop solutions that meet the needs of your culturally unique clientele.”

Sometimes members of Abacus’ “culturally unique clientele” were assisted in quests to purchase homes with monies provided by family and friends—a cultural practice known as hui. The prosecution deemed the bank’s use of gift letters to document these monies to be fraud. These “gifts,” the prosecution said, were in fact loans, and contributed to the insecurity of the mortgages originated by Abacus. But in the culture of the bank’s clients, these monies were neither gifts nor loans, but something more akin to support, given without expectation of repayment. The defense relied on the bank’s miniscule default rate as evidence that its lending judgments were sound and not fraudulent. Whereupon, the prosecution told the judge during a pretrial hearing that the Sungs were demanding that a cultural exception be made for them because they are Chinese, and Chinese people don’t default on their loans. That cultural smack still stings. “We were not saying that we deserved an exception. And how can we know that people are not going to default on their loans other than through sound underwriting?” Vera says. “We were saying that default is a red flag for fraud.”

On a Rappaport Center for Law and Public Policy panel that included Vera and Chanterelle at the Law School last fall, Terence McGinnis ’75, Massachusetts Commissioner of Banks, raised the concept of “character lending” to describe how a small community bank like Abacus makes loan decisions. Arguably, the DA’s dismissal of Abacus Bank’s exceptionally low mortgage default rate as evidence that its lending practices were sound was a rejection of the legal validity of character lending. An alternative interpretation is that the DA was culturally tone-deaf. “What I think is problematic is that you have a criminal justice system that sits over a cultural community that it is not sensitive to and that it doesn’t recognize,” says Chanterelle. “That is not going to work. The people who run that system must be willing to understand the community. Otherwise, you’re just going to impose these arbitrary rules on top of a community that is completely legitimate and is completely legitimate in what it is doing, and end up with these perverse results.”

On May 19, 2015, the three-month trial came to a close. The jury deliberated for eleven nail-biting days. On June 5, 2015, the New York Times reported: “After a court clerk read the 240 counts in the indictment and repeated the words ‘not guilty’ after each one, members of the Sung family wept and embraced one another in State Supreme Court in Manhattan.”

The bank’s employees who had been indicted were either acquitted or had the charges against them dropped. The trial had kept an employee from attending his mother’s funeral in Hong Kong, and he was so traumatized by the ordeal that he can no longer bring himself to sign a check. Defending the bank cost the Sungs $10 million in legal fees, and likely another $10 million in lost business.

In a statement to the press drafted with his daughters’ input, Thomas said, “This wrongful prosecution has exhausted a small community bank such as ours. This is a gross injustice, not only to a small bank, but is casting a shadow on our community. This is totally prejudicial and incorrect.”

The DA’s office was unrepentant. In a startling twist on the foundational American ideal of “innocent until proven guilty,” one of the prosecutors said, “Abacus was not exonerated. Exoneration is when a person is proven innocent. I don’t think there’s anything here that says that Abacus was proven innocent.”

The Sungs are healing from their ordeal, and drawing strength from the voice that the documentary has given them. Vera, Chanterelle, and Jill speak around the country, raising awareness about prosecutorial overreach and the plight of underbanked cultural communities in America. Abacus is now turning a profit and has resumed making loans.

Most of all, Abacus is back to fulfilling its mission. “My dad has always said to us that if he ever saw that the community did not need him anymore, he would have no qualms in closing the bank, because that’s what he formed it for—the community,” says Vera. “But there is still a need, so we have to still be here, and we have to still do what we are doing.”