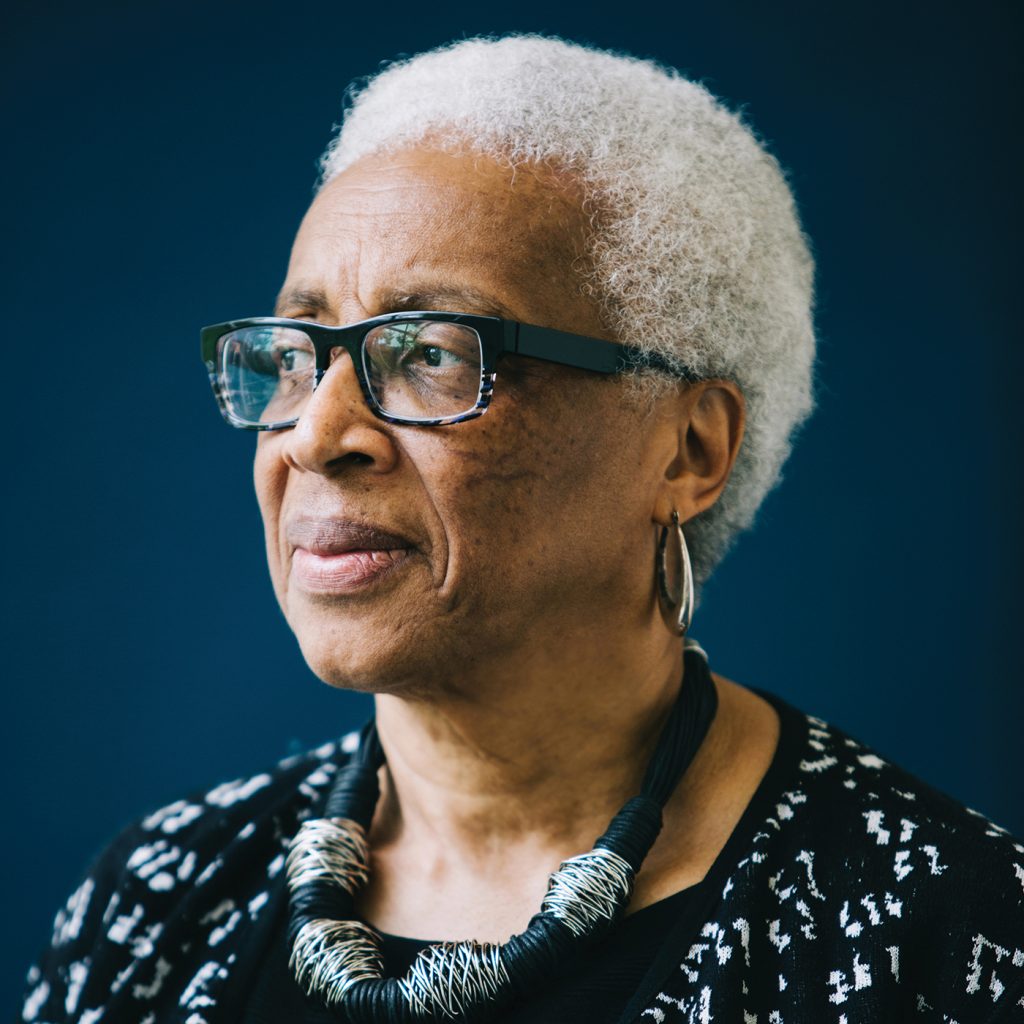

Raised in the “Jim Crow” South, Geraldine Hines has been a public defender, name partner in a law firm, and a justice of the Supreme Judicial Court of Massachusetts. She recently taught a course on race and policing as the Jerome Lyle Rappaport Visiting Professor at BC Law. As a young lawyer, Hines served as co-counsel in Commonwealth v. Willie Sanders, successfully defending an African-American father of four with no criminal record against multiple rape counts.

VR: I understand that seeing how racism threatened to undermine justice in the rape case Commonwealth v. Willie Sanders was a pivotal moment in your early career.

GH: Yes. For one thing, Mr. Sanders was charged based on very weak evidence; the police used an identification process that we don’t permit today. Also the judge in the case belonged to an old guard who saw their role as taking down black defendants, but his racism backfired. He barred me from a pretrial conference, supposedly because I wasn’t lead counsel, and I wasn’t having it. We complained to the chief justice of the superior court, who replaced this judge. The new judge—one of two black judges on the bench at that time—let us do an engaged jury selection process, and the jury we selected voted to acquit.

VR: This kind of case was the worst nightmare of every person of color, particularly in the 1980s and ’90s, when this sense of black male criminality permeated urban spaces. Women clutched their purses or crossed streets when they saw you. Taxis wouldn’t stop for you. Even downtown you’d hear slurs. So cases like this were a constant reminder of how tenuous our hold on citizenship was.

GH: People aren’t throwing bricks at school buses full of black kids anymore, but we still have the kind of structural inequities in Boston and the country generally that indicate a lack of progress. I think people confuse change with progress. They’re two different things.

VR: Our national politics have reasserted the notion that you’re disloyal if you say we still have problems, like economic inequality and police shootings, that harm people of color disproportionately. Your course spring semester on race and policing examined some of those problems.

GH: Many students planning on corporate law careers took my class. I was amazed at their interest in the topic. They wanted to understand why people are taking to the streets, why communities and police come into conflict.

VR: The course was enormously well received and said good things about our students that those who aren’t going into criminal law still want to take it. I hope this signals their recognition that all lawyers are responsible for these issues.

GH: I tell students that even in corporate jobs you can bring understanding and empathy. We discussed Bank of America, which started charging fees for checking accounts with balances under $1,500. I said, “OK, you’re in banking. You’re with the bigwigs when they’re deciding how to maximize profit. You may not change the policy, but somebody at the table might say, ‘Maybe we can pad our bottom line elsewhere and not on the backs of poor people.’”

VR: Terry v. Ohio (1968), which greatly expanded police power, was central to your course.

GH: You’re taught in civics that Supreme Court justices decide cases based on law alone. But Terry reached the court a year after riots in Cleveland and Watts, and months after the King assassination. So the Warren Court, while it made some positive changes on civil liberties, had heard concerns about people getting out of line and tearing up cities. The NAACP warned that a decision for the state would harm communities of color, but the court didn’t listen.

The opinion lets police stop people based on reasonable suspicion instead of probable cause. The issue gets litigated in a thousand motions to suppress: “The police lacked reasonable suspicion to stop him.” And it’s a complicated calculus because whether someone looks suspicious involves implicit racial bias.

Judges know the code words: “He had a hand inside his waistband.” And once you stop someone, it’s easy under the law to justify a frisk. Let’s say police frisk someone and find drugs or a gun. That puts this person on a collision course with the criminal justice system and all it entails. It’s hard to appreciate what stop-and-frisk does to the fabric of society and our trust in government. And studies show that it doesn’t reduce crime much.

VR: Terry and its progeny also feed into non-police actions like the recent Starbucks incident. The presence of black men not buying things made the store manager “reasonably” suspicious. The broad assumption that black or brown males in a public space represent danger comes in part from how they’re viewed by the police.

We need to make sure our students understand these issues. We should also help people understand what the police are dealing with. I hope we can get police and communities to think more constructively about their interactions.