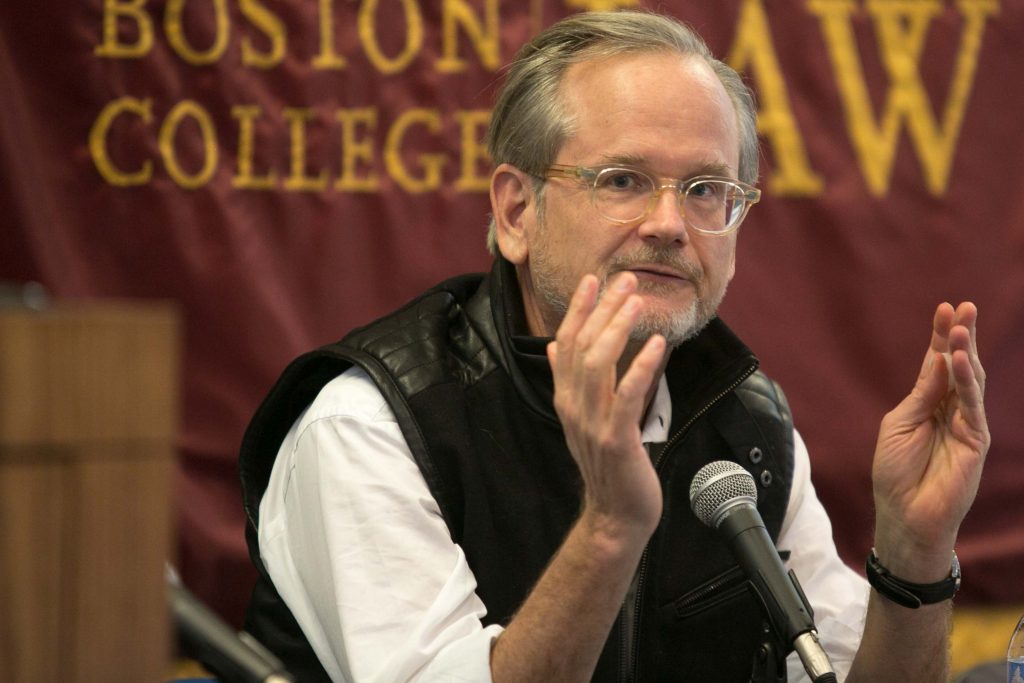

Calling the Electoral College one of the “least understood disasters at the core of our Constitution,” Harvard Professor Lawrence Lessig (above) launched a Rappaport Center for Law and Public Policy discussion convened to explore the pros and cons of the body that gets the last word on presidential elections.

The October 18 event, “Electoral College: Stay, Go, or Alternatives,” brought Lessig together with John Brautigam, a former Maine state representative and assistant attorney general, and Rebecca Burgess of the American Enterprise Institute. BC Law Professor Ryan Williams moderated.

The result of the Electoral College, Lessig claimed, is a “president based on an unrepresentative minority,” which leads to presidencies that focus disproportionately on swing state interests and voters. The most realistic solution, according to Lessig, is to institute proportional allocation of electors, as is the case in Maine and Nebraska.

Brautigam seconded Lessig’s assertion and spoke highly of the effect the system has had on the political system in Maine, contrasting it with “winner-take-all” states such as Massachusetts. Currently, whichever presidential candidate wins the majority of votes in the Bay State secures every one of its eleven representatives to the Electoral College, contributing to the 270 electoral votes needed to secure the presidency. Had proportional allocation been instituted in Massachusetts during the 2016 presidential election, nearly 1 million Republican voters would have had some sort of representation within the Electoral College.

Likewise, Brautigam described Maine’s ranked-choice system as an avenue taken by the voters to more accurately capture preference in elections. A product of a ten-year grassroots movement, ranked-choice has survived both constitutional and legislative challenges and will be used in the upcoming midterm elections. While it is not directly connected to the presidential electoral process, it impacts local, state, and congressional races.

Rather than voting for one candidate, Maine voters are tasked with ranking candidates in order of preference. If one candidate secures an outright majority, she is declared the winner. If no candidate reaches this threshold, the candidate with the fewest number of first-choice votes loses and her votes are reallocated to their second choice. This process continues until one candidate reaches a majority.

Brautigam reports that besides giving voters a greater role in the process, ranked-choice has led to less negativity among candidates as they shuffle to become a voter’s second or third choice.

Slightly changing the course of the discussion, Burgess expressed support for the Electoral College, explaining the while she is aware of the issues surrounding the system, she believes it is the most practical means to create a free, independent choice for citizens. Noting that government is created to secure the rights of all, Burgess explained that while the status quo may not provide a voice to the greatest number of people, such as those 1 million Republican voters in Massachusetts, it does provide protection for those who fall outside the greater number. In short, the Electoral College is a system of moderation, providing a bulwark against a tyrannical majority, she said.

At various points, each panelist expressed a strong desire to make voting more accessible and concern for the extremism plaguing the major political parties. Noting the seriousness of the issue, Lessig ended his remarks by reminding the audience that “we have a very short time to get this right.”