Intelligence is a shameful thing to waste. As a friend who works for a nonprofit providing housing in low-income neighborhoods is fond of saying, there are kids from every population who are going to be leaders, and they show up at random. Whether you take them in and love them or push them out and hate them, they will be leaders anyway. So, he asks, what kind of world do you want?

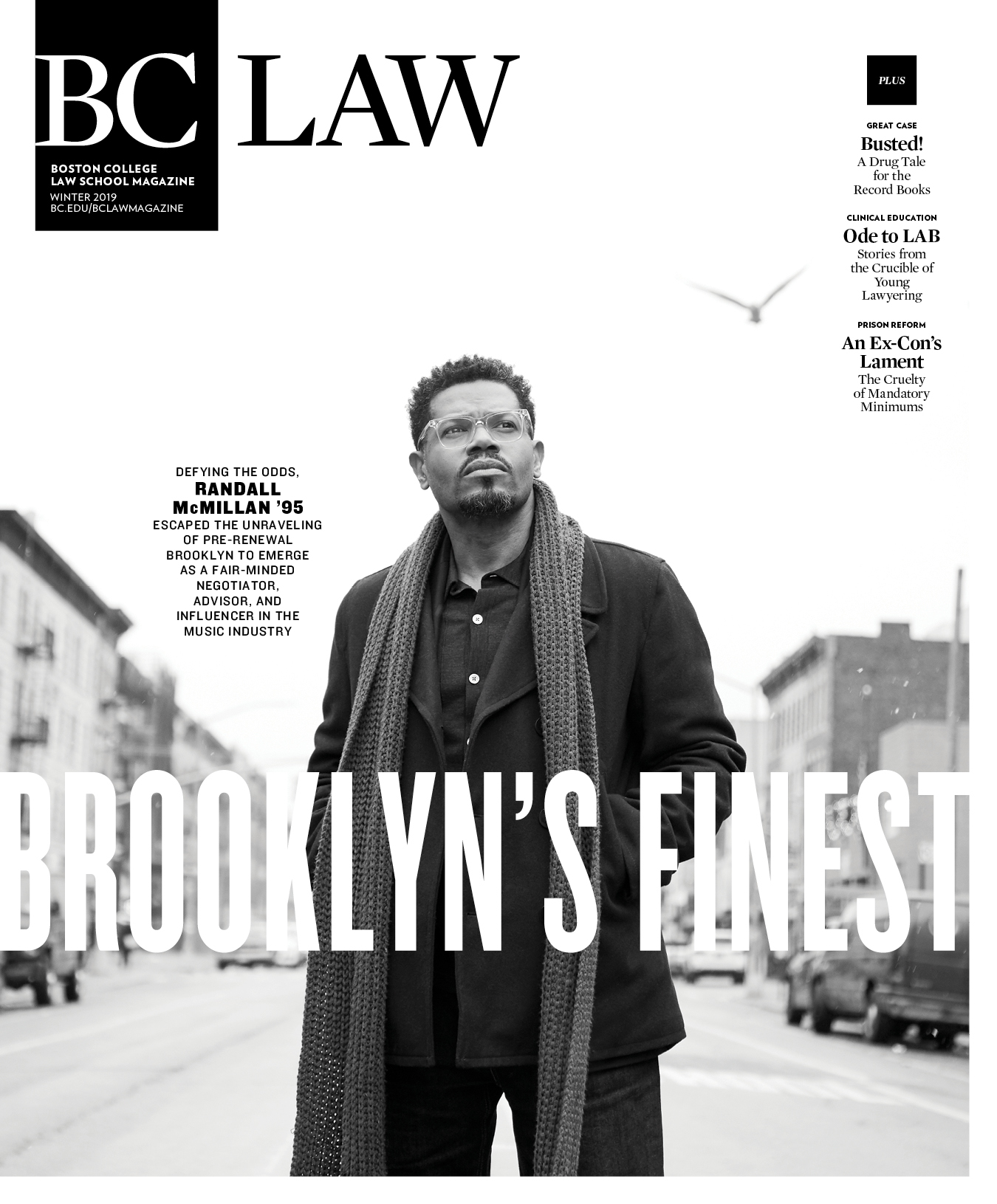

His question brings to mind our cover story about Randall McMillan ’95, who was raised in a struggling, violence-prone Brooklyn neighborhood, a place that broke some of his best friends and damaged many others. He saw the bad temptations. He could have succumbed. So what enabled this child of urban dysfunction to survive and ultimately thrive at the top of America’s music industry instead?

The psychologist Howard Gardner theorizes that multiple intelligences contribute to an individual’s performance. He breaks these down into eight components: logical, spatial, linguistic, interpersonal, naturalist, kinesthetic, musical, and intrapersonal.

Humbly and in quiet statements and recollections, McMillan emerges as a fine example of both my friend’s and psychologist Gardner’s observations—that strength comes in many guises and out of many backgrounds, that leaders are not made, they are born. And they are loved and respected along the way.

Have a listen: “There were many things I wasn’t able to participate in…. Music gave me an outlet,” McMillan says. “[It] helped me feel connected to what was happening in the streets that was positive, as opposed to what was dangerous. It made me feel like I was part of my environment, yet connected with the things that were blossoming, not dying. It let me outside of those artificial borders my grandmother set for me. I honestly think my eclectic interest in music during those years is why I’m here today…. I think that’s a parallel to when I’m deal-making in the music business.”

Cornell University taught other lessons. “Adapting, effectively communicating, and negotiating two different worlds—where I was from and where I found myself—became integral to my own survival and success. I learned how to listen more and identify the crux of what was important to people,” McMillan explains. “I realized that interfacing that way would allow me to accomplish whatever my agenda was.”

A brain—allowed the space to grow and flourish—is what McMillan’s story allows us to witness. There is a lot there. Read on.

Vicki Sanders, Editor

vicki.sanders@bc.edu

Photograph by Diana Levine