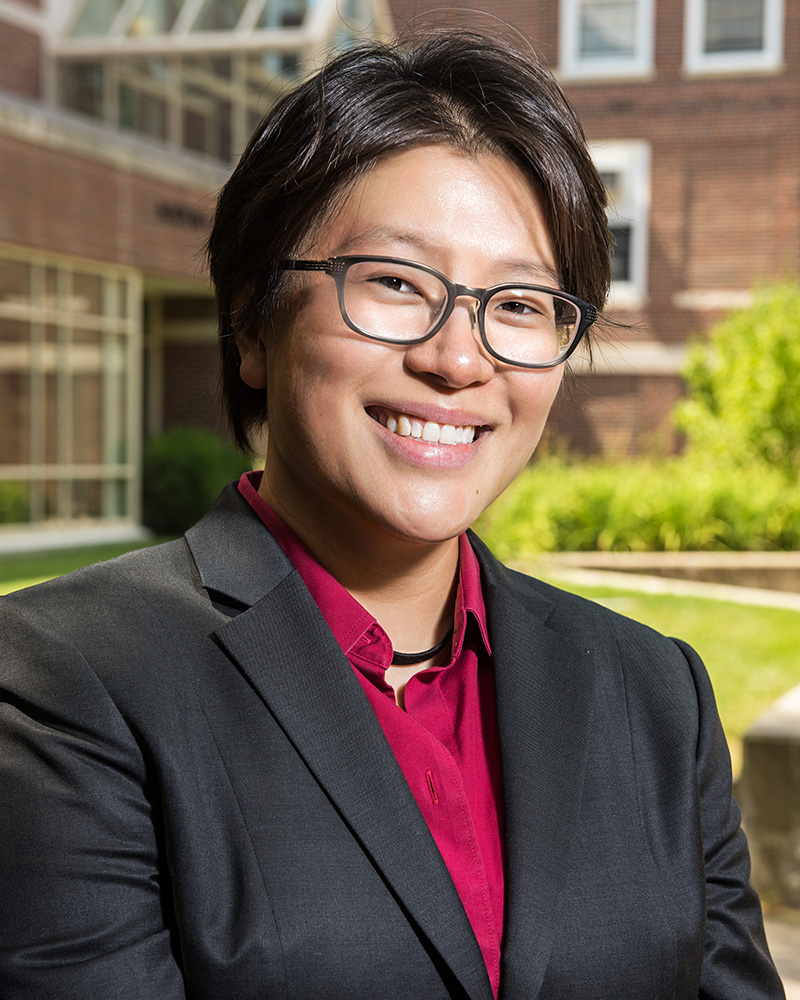

Pocket Résumé

Degrees: BA magna cum laude, Brown, 1999; JD and MTS, Harvard, 2003. Credentials: Professor, BC Law, 2017-date. Professor, Tulane Law School, 2009-2017, as inaugural holder of Hoffman F. Fuller Professorship in Tax Law and recipient of 2014 Felix Frankfurter Distinguished Teaching Award, the school’s highest teaching honor. Tax associate, Bingham McCutchen, 2003-2009. Specialties: Teaches and writes in the areas of tax policy and economic regulation. Writing: Articles in law reviews at UCLA, University of Pennsylvania, Emory, Iowa, Vanderbilt, McGill, and many others.

The Idea: Unorthodox lawmaking begets unorthodox agency rulemaking. During the US Treasury’s rulemaking that followed passage of the hastily drafted 2017 income tax bill, corporations and industry groups tried to influence the rulemaking by submitting requests for favorable treatment before the official public comment period. These early comments seem to have had outsized influence on some regulations.

The Impact: Though not slated to be published until 2020 in the Emory Law Journal, an article coauthored by BC Law Professor Shu-Yi Oei and Leigh Osofsky of University of North Carolina School of Law on the making of the regulations interpreting the 2017 tax law is already turning heads in tax circles. An online post by Samantha Jacoby of the Center for Budget and Policy Priorities featured a lengthy writeup. That same month, the paper placed high on the Yale Journal on Regulation’slist of most downloaded recent papers, second only to an article by legal superstar Cass Sunstein. On the Procedurally Taxing blog, Professor Keith Fogg of Harvard called the article “eye-opening in its detail.”

Oei and Osofsky’s article looks at a section of the new tax law (§ 199A) that allows up to a 20 percent deduction of income earned by certain sole proprietorships, S corporations, and limited liability partnerships—so-called “pass-through” businesses. Possibly because of the law’s hasty drafting—scant time was devoted to committee hearings and last-minute provisions were added to the bill—much of the statutory language was ambiguous, leaving significant questions for Treasury rulemakers to answer.

Federal agency rulemaking starts with the issuance of proposed regulations, followed by a public comment period, and then final regulations. The opportunity for public comment is meant to increase the democratic legitimacy of a process overseen by unelected bureaucrats, but Treasury-proposed regulations have generally drawn few comments, according to Oei. This was not the case with the new pass-through provision. Not only were 337 comments logged by Treasury during the comment period, but fifty-one more comments arrived before the issuance of proposed regulations, a fact that the authors discovered by consulting the TaxNotes subscription service. (Comments submitted during the official period were publicly posted on a government website, regulations.gov, but the early comments were not.)

During the rulemaking that followed passage of the 2017 tax bill, corporations and industry groups tried to influence the process by submitting requests for favorable treatment before the official comment period.

While fewer than those received during the official period, the early comments weighed heavily in the rulemaking. Treasury mentioned many in its preamble to the proposed regulations. The authors describe early commenters as “sophisticated actors” like trade organizations that hoped jumping the gun would garner favorable tax treatment. By contrast, timely commenters were mainly smaller and less sophisticated taxpayers and advisors like independent CPAs, to whom it had likely not occurred to comment early. As Oei puts it, “If you’re a small CPA in Nevada, that’s not your jam. You’re not constantly on the Hill talking to Treasury.”

Early commenting worked, says the article, or at least it was “highly correlated” with the granting of one’s wishes—even wishes that might seem overreaching. Thus, banks organized as S corporations got their income qualified for the full deduction even though the statute limits the deduction for “financial services” businesses, while real estate and insurance brokers got the full deduction despite statutory language excluding “brokers.” The article also cited cases where groups that commented early got several bites of the apple by having their wishes incorporated, and then asking for more during and even after the public comment period.

Despite the appearance of powerful interests having secured positive treatment, the article stops short of asking for a ban on early comments. For one thing, Oei says, “people would probably find a different workaround.” It also may not be realistic for Treasury to draft proposed regulations in complete isolation. If proposed regulations widely miss the mark (from lack of conversation in the drafting stage) and significant changes to the regulations are needed, then Treasury may need to start the process over rather than making more modest changes and issuing final regulations. Relatedly, not all early commenters were self-interested; some were tax experts whose ideas helped Treasury clarify issues.

Instead of a ban, the authors call for changes in the handling of early comments. They want Treasury to publicize its openness to comments that arrive between the passage of a new tax law and when proposed regulations are issued “and flag the questions they are considering as early as possible so as to generate as broad a swath of comments [as possible].” They’d also like Treasury to post all comments publicly on regulations.gov.

That may not level the playing field, but it would at least add some transparency to a process sorely in need of it.