For most of us, what qualifies as an epic music debate is wholly subjective and undertaken all in good fun. Zeppelin or the Stones? Beyoncé or Adele? Prince or Pink? For Jeff Gould ’06, making an argument about music was a whole order of magnitude more complex when he took on a copyright infringement case that pitted the majority of the music industry against one of the nation’s largest internet and broadband companies.

The claims? Contributory and vicarious copyright infringement for more than 10,000 songs. The plaintiffs were Sony Music Entertainment, Universal Music Group, and Warner Music Group—known as the Big Three record labels. They own rights to the majority of recorded music sold in the US and worldwide, along with their music publisher counterparts, which own or control the underlying musical compositions. The defendant was Cox Communications, the nation’s third largest cable company and eighth largest internet and broadband company. The case included more copyrights at issue, it is believed, than any other in history. It also targeted a larger, more profitable defendant than nearly all other copyright cases. Further complicating matters, the et al. following the lead plaintiff, Sony, consisted of fifty-three affiliate record companies and music publishers.

Tasked by Sony with wrangling that legal behemoth into a comprehensible—and winnable—case were Gould and a small band of colleagues at the DC-based copyright boutique, Oppenheim + Zebrak, LLP. The speed alone with which they had to act was daunting, though not surprising, given that the case venue was the US District Court for the Eastern District of Virginia (EDVA), aka “The Rocket Docket.” The news service Law360 reported that EDVA litigated its way to the nation’s shortest average duration from file to trial in 2019—for the eleventh year in a row.

“Our case went from complaint to a trial in seventeen months,” says Gould. “Anybody who’s ever tried complex litigation knows that is extremely fast. When you think about it in the context of a case this big, it feels even faster. And years shorter, on average, than the time between complaint and trial for civil litigation in this country. What does that mean for us? It means we work very, very hard.”

Our story begins with a scrappy rink rat who never met a hockey game he wouldn’t skate to win. A Vermont native, Gould mostly grew up near Chicago, but returned to New England to attend Phillips Exeter Academy, where he played ice hockey. A 5-foot-9 and 165-pound shoot-first right winger with a knack for finding the back of the net, Gould still plays the game in what he calls a “beer league.” “Put it this way, I would never have been up to the task of playing at the level of BC as an undergrad (or even Williams College, where I went), but I’ve always come at things from that offensive angle, which can be a helpful attribute if you do a lot of work in the plaintiffs’ bar.”

Sony v. Cox was definitively a drop-your-gloves sort of legal action. Discovery, alone, became a deluge of documentary analysis and depositions. On the final day of the window, Gould conducted a 3 a.m. deposition via videoconference of an anti-piracy software engineer in Vilnius, Lithuania. That concluded a wild stretch during which the Oppenheim + Zebrak (O+Z) team executed thirty-nine depos in forty-five business days, including double- and triple-tracking offensive, defensive, and third-party depositions across the country and around the globe on any given day.

“It was bonkers. Absolutely bananas. Off-the-charts insane,” says Gould.

What’s more, O+Z is a boutique outfit. There were ten attorneys on staff when the firm landed the case. Gould, forty-four, had been there just fifteen months when O+Z filed the Sony complaint. And it was a doozy. Sony alleged secondary copyright infringement claims against Cox based on the defendant’s hand in its subscribers downloading and distributing 7,068 copyrighted sound recordings and 3,452 copyrighted musical compositions owned by plaintiffs—all the while prioritizing its own profits over limiting infringement it knew was occurring on its network.

Gould was tailor-made for a seat at the plaintiffs’ table and for his duties managing the litigation day-to-day, which is a lot like running point on the power play. After BC Law, he served as a law clerk to Judge Paul J. Barbadoro of the US District Court for the District of New Hampshire before joining the DC office of Kirkland & Ellis LLP, first as an associate and then as a partner. During his ten-year stint at Kirkland, Gould focused his practice primarily on complex commercial disputes in federal and state courts.

Paul Tremblay, a clinical professor at BC Law and director of the Community Enterprise Clinic, recalls spotting Gould’s knack for litigation from as far away as a blue-line slap shot. “We all knew he was going to be super successful,” Tremblay says. “He worked with me in what was then the eviction defense clinic. His group was great, but he was a star. He was so talented as a student. He came to law school with a lot of confidence and poise. You just felt like he was someone who was going to go far.”

Gould, the father of seven-year-old twins, joined O+Z in 2017 and has focused mainly on complex litigation and counseling in intellectual property and commercial disputes, with an emphasis on copyrights, trademarks, and related commercial matters. Besides its music clients, O+Z represents major book publishers and other content and brand owners.

Judge Barbadoro believes he can actually pinpoint the case that set Gould on a collision course with Cox Communications. “I remember working with Jeff on a criminal securities fraud prosecution of an officer and several senior managers at a publicly traded company,” says Barbadoro. “The trial was long and complex. It resulted in convictions and lengthy prison sentences for the defendants. Jeff played a central role in working with me on that throughout, and he later told me that case was one of the things that got him hooked on litigation. I’ve hired more than twenty recent BC graduates to work for me as clerks, and they’ve been uniformly excellent. Jeff certainly fits that mold.”

“It was bonkers. Absolutely bananas. Off-the-charts insane.” —Jeff Gould on taking depositions preparing for trial

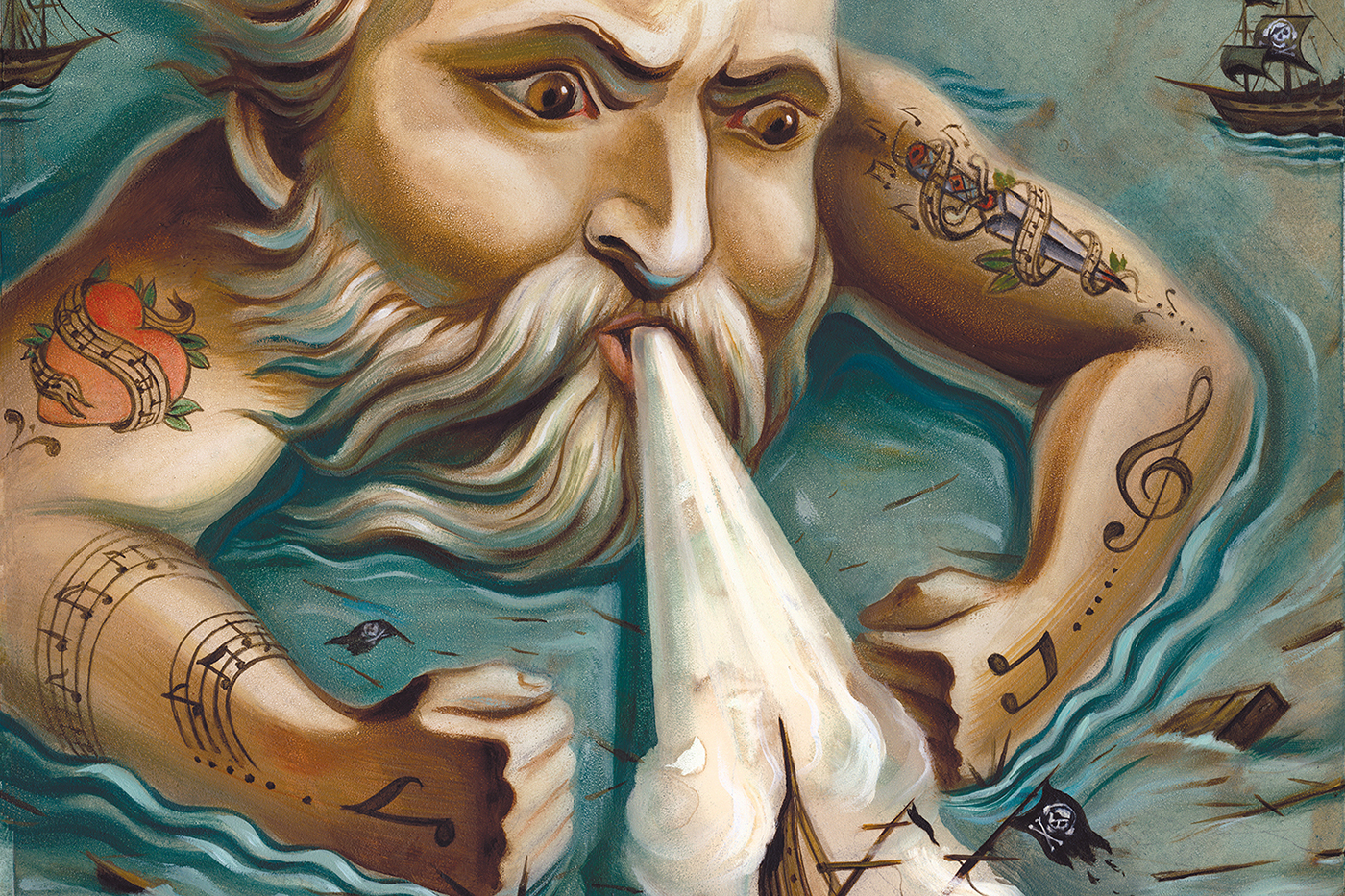

GOT YOU UNDER MY SKIN

For more than a generation, since the heady days of Napster (circa 1999), third-party file-sharing sites where users can download digital audio files without paying for the content have tormented the music industry and the artists it represents in matters of copyright infringement. For every Napster or Grokster snuffed out by legal action, another open-source software tool sprung up in its place.

Prosecuting individual offenders amongst the general public proved impractical—whack-a-mole, if you will. So Gould and O+Z sought to stem the tide at the source of the direct infringers’ access—internet service providers (ISPs) that ignore their obligation to act in the face of specific knowledge of illegal infringement. Under the law, an ISP can’t knowingly contribute to copyright infringement, nor can it profit from infringement it has the right and ability to stop. ISPs like Cox may be entitled to a so-called “safe harbor” from secondary liability under the Digital Millennium Copyright Act, but here Cox did not qualify for that protection.

In its complaint, Sony alleged more than 10,000 individual works had been pirated illegally over a two-year period, painting a picture of a Cox culture that systematically abetted infringers and openly mocked copyright laws by ignoring hundreds of thousands of notices from copyright owners. Cox boasted 4.5 million subscribers and reported nearly $20 billion in revenue and more than $8 billion in profit in the two-year claim period alone. According to Sony, the defendant was flaunting the rules to keep collecting service fees from tens of thousands of customers who flouted Cox’s Acceptable Use Policy by using its service to infringe.

Attorneys for the defendants disputed the charge, hammering home themes about its customers’ right to privacy, the company’s role in providing internet service for critical infrastructure like banks and police, and its purportedly state-of-the-art graduated response system.

In trying the case, Gould and the O+Z team had to battle the double-edged sword of a jury trial. They needed to steward eight jurors in a manner that allowed them to extract actionable facts and persuasive pathos from testimony and documentary evidence over the course of a two-week trial about network nuances, data transmission, and software functionality. All in the course of considering a monolithic 5.8 million infringement notices directed at Cox and its tens of thousands of faceless subscribers tabbed as repeat offenders.

There was another paradigm-shifting aspect of the case. In addition to its contributory infringement claims, Sony was seeking to be the first music industry plaintiff to get a claim of vicarious liability to stick against an ISP. But before they even got to the plate on that allegation, the plaintiffs had to prove the underlying claims of direct infringement by Cox’s subscribers.

The stakes were always high given the number of copyrights at issue. Statutory damages awards under the Copyright Act can range from $750 to $150,000 per work infringed, and the law confers juries with broad discretion to assign a damage award within that range, including any apparent need to compensate the plaintiffs and deter/punish the defendant. A maximum damages verdict would set Cox back somewhere in the neighborhood of $1.58 billion, which sounds like real money—even to a company that paid its owners $2.9 billion in cash dividends from 2012 to 2014.

O+Z knew the jury could get lost in how all the technology worked and defendant’s efforts to distract. To avoid that, Gould and his team focused on building a story everyone could relate to. “It’s so hard to do because the nature of trial presentation is that you build blocks from different witnesses and documents not necessarily in any obvious, linear way,” explains Gould. “Trials can be very disjointed. We need to take all of the pieces and put them back into a storyline so the jury sees the end of the story and not just the different chapters.”

“Copyright infringement is not a victimless crime. Cox harmed recording artists. It harmed songwriters. It harmed everybody in the ecosystem. Back-up musicians, union musicians, digital engineers. Everybody.” —Matt Oppenheim O+Z, Managing Partner, who sat first chair for the plaintiffs

THRILLER

“Copyright infringement is not a victimless crime,” says O+Z Managing Partner Matt Oppenheim, who sat first chair for the plaintiffs at trial. “Cox harmed recording artists. It harmed songwriters. It harmed everybody in the ecosystem. Back-up musicians, union musicians, digital engineers. Everybody.”

That thesis statement underpinned the lawsuit, ultimately becoming its chorus. Gould and the O+Z team made sure to make it about the music. “Making it about the art brings back the real, tangible importance of the music,” adds Gould. “So for each record company exec who testified at trial, we presented a witness who was telling the court and jury about the universality of music and how there’s personal meaning we draw from individual works—the way you can hear a certain song and it takes you back to cruising around in high school with buddies, or a great family vacation that you had, or the first-time-you-ever stories.”

But the plaintiffs did more than that. Amidst testimony, objections, and argumentation, they played medleys of songs from the respective labels. Riffs and back beats from R&B, reggae, classic rock, pop, folk, and country da-danged from the courtroom. The jury got to groove to Prince, Van Halen, and James Taylor (Warner Music), plus the Rolling Stones, Beyoncé, and Eric Clapton (UMG), as well as Springsteen, Whitney Houston, Billy Joel, and Adele (Sony).

“These were great moments at trial and we did that very deliberately,” says Gould. “Cases like this can become all about the elements of the legal standard. Frankly, it’s easy to forget about the music. So, we spent time and effort and energy collecting and arranging powerful music that we would play.”

Punctuated by head-bobbing interludes, Sony unleashed a torrent of damaging evidence at trial, including a well-documented audit trail detailing the monitoring and reporting of Cox subscribers’ infringement, which offered solid evidence of underlying direct infringement (downloading and distribution) of their copyrighted works by Cox users. It became clear that Cox had subscribers who were infringing en masse, and that the music industry kept telling Cox about it.

Cox countered, arguing it is bound by strong security policies that protect its customers’ privacy; ISPs don’t track down what subscribers are doing online and the burden of policing shouldn’t fall to them. Secondly, the company contended that it is merely a gateway to the internet—that’s the business model. It doesn’t host or edit content. It’s a mechanism for individuals to access the web. Put another way: Don’t blame the messenger.

“What you don’t know until you pull back the curtain and see Cox’s internal documents is that they made a mockery of what the record companies and the music industry were saying,” says Oppenheim. “What Cox really did was develop a policy where the whole point was to avoid doing anything.”

Cox scoffed at that notion, touting its development of a first-in-time, best-in-class graduated response program to infringement that was addressing such issues 24/7/365. The record didn’t corroborate that claim. Cox ignored user behavior over and over again, but kept responding to infringement notices with a thank you and a promise to do something about it. Plaintiffs presented evidence of more than 10,000 infringements per day on Cox’s network. But how could the theft of 10,000 works in total be the subject of 10,000 instances of infringement per day? Because millions of Cox customers were downloading the same songs. It’s called pop music for a reason.

There was another paradigm-shifting aspect of the case. In addition to its contributory infringement claims, Sony was seeking to be the first music industry plaintiff to get a claim of vicarious liability to stick against an ISP. But before they even got to the plate on that allegation, the plaintiffs had to prove the underlying claims of direct infringement by Cox’s subscribers.

BREAK ON THROUGH

To have a chance at deterring Cox and other ISPs, Sony had to win on its contributory and vicarious claims. That meant Sony needed to establish an economic incentive for Cox to tolerate infringement as well as to show that Cox material contributed to infringement it knew about.

Trial evidence showed that Cox repeatedly said one thing and did another. Cox “gamed their own policy” Oppenheim said in his closing arguments. The company had an Acceptable Use Policy in its customer agreement that prohibited use of its network for copyright infringement. It employed a counter-abuse team.

But the whole thing was “a sham,” argued Oppenheim. Conduct by Cox’s security and marketing teams was arbitrary, capricious, and seemingly motivated by malice at times. For starters, as a matter of course, the abuse team ignored the first infringement notice it received with respect to any individual subscriber. The defense argued that Cox wanted an opportunity to educate customers on the terms of their agreement, but more often than not, Cox wouldn’t even forward the notices it was receiving. Rather, Sony showed that Cox deleted most of them without taking any action at all.

The company capped its daily account suspensions at 300, a limit routinely met by 9 a.m. Cox also set hard limits on the number of notices that it was willing to receive from different copyright owners, either silently deleting them, or simply rejecting notices automatically at the mail server. The effect was to ignore millions of notices, with no customer-facing action. Was this endemic? One member of the compliance team tapped out an email that read: “We need to cap these suckers.”

The defendants conceded all of the above, adding that, sure, Cox didn’t follow up on all of the 270,000 infringement notices it formally processed from the Big Three during 2013 and 2014, but the system it had in place to warn and punish abusers was “extraordinarily effective.” What’s more, Cox argued, those infringement notices sent by the plaintiffs weren’t really specific enough to consistently act on anyway.

Not true. In trial testimony, Cox admitted receiving nearly 5.8 million infringement notices during the relevant years, not counting millions more it blocked or deleted. And, the information in the notices from the labels wasn’t vague. Each notice alerted Cox to the individual subscriber by IP address and included examples of infringement at a particular date and time as well as a cryptographic hash value—a digital signature or fingerprint, that tells software engineers: This downloaded file is identical to the file you know as: “Lady Gaga, Poker Face.”

Cox also abolished the mandatory termination provision of its Acceptable Use Policy (AUP) and made it discretionary with a graduated structure. The new provision began with a three-strikes rule, but over time, as the number of notices mounted, Cox amended its policy to ten steps, then twelve steps, then fourteen steps. As the problem grew, Cox changed the rules to avoid friction with customers and continue providing them service, for which they collected money.

“Where else in the law are you given fourteen opportunities to obey the law?” demanded Oppenheim in his closing argument. “And as far as capping the number of notices it received, the notion that an ISP can put its hands over its ears so as not to hear about infringement on its network has no place in the law. Cox does not get to limit copyright owners on the amount of theft they report.”

During the claim period, Cox also offered a tiered pricing plan, charging different flat fees for different download speeds. For the uninitiated, a content pirate is not in the game to wait around for any download speed but the fastest.

Further testimony and trial exhibits revealed that suspended customer accounts would often be reactivated within hours. As for oversight, the company slashed its Technical Operations Center abuse team from fourteen to nine members and, ultimately, four. At a company that employs 20,000 people. Turns out that internally, Cox readily acknowledged it had a massive economic incentive to tolerate infringement. It was right there in the discovery docs, brought to life in the form of dozens of emails among Cox employees.

As one executive wrote in an email, “Remember to do what is right for our company and subscribers, not to do what [this customer] is obligated to do under the law.” The head of the abuse team urged workers to give repeat infringers a “clean slate” following a soft termination and reactivation so that Cox “could collect a few extra weeks of payments for their account ;-).” He instructed his team “to hold on to every subscriber we can” and to “keep customers and gain more RGU’s” (i.e., revenue generating units, also known as subscribers).

Missive after electronic missive from Cox’s abuse team demonstrated this company-wide approach. “This customer will likely fail again, but let’s give him one more chance—he pays $317.63 a month.” In another example, “this customer pays us over $400/month and if we terminate their internet service, they will likely cancel the rest of their services.”

Cox insisted its conduct was driven by a sense of corporate responsibility. As the provider of an essential service, the company couldn’t be hasty or impulsive about suspending or terminating accounts. Especially its business customers, made up of hospitals and city halls and military installations. But trial evidence showed Cox terminated over 619,000 customers—including 22,000 business customers—who were a month or so behind on their bill during the claim period. By contrast, the company terminated a mere thirty-two accounts in response to copyright infringement, despite knowing of tens of thousands of repeat infringers.

The truth was, Cox’s policies did virtually nothing to uphold the company’s AUP. In fact, email records revealed that the counter-abuse manager and his lieutenant crowed “f the dmca!!!” (the Digital Millennium Copyright Act that established the framework for plaintiffs to send Cox the infringement notices).

Late in the trial, Cox introduced 1,200 emails reflecting warnings sent to customers informing them their activities were illegal and the customers’ responses. Gould did his due diligence and read them all between trial days in preparing to redirect a witness the next morning. Buried in the pile was an email from a customer who—clearly well aware of his actions and, after years of this behavior, irritated he had suddenly received a caution—responded, “I have [an open-source] application on my computer that’s been there for a couple of years. If [this] is illegal, kiss my you know what.” Gould piled on in his redirect of the abuse engineer who received the email, showing that the same customer infringed unabated thereafter. It was not a good moment for the defense.

Ultimately, Cox’s top counter-abuse engineer admitted under oath that financial considerations were a factor in making decisions about whether to terminate an infringing subscriber.

“[Jeff] was so talented as a student. He came to law school with a lot of confidence and poise. You just felt like he was someone who was going to go far.” —Paul Tremblay, BC Law Professor

LET IT BE

Following a twelve-day trial last December, a Virginia federal jury needed one full day of deliberations to find Cox liable for willful vicarious and contributory copyright infringement. The jurors awarded $99,830.29 for each of the 10,017 works infringed upon, adding up to exactly $1 billion. The verdict is the largest in music industry history and the second-largest copyright verdict ever. It was the largest jury verdict in the history of the EDVA by a factor of more than thirty. In late June, Law360 listed the case among its “Top 7 Copyright Rulings of 2020” midyear report. Gould played a central role in the case from start to finish, including handling ten witnesses at trial.

In a January memorandum asking the court for either a new trial or a reduction in the damages amount, Cox claimed the award “exceeds the aggregate dollar amount of every statutory damages award rendered in the years 2009-2016 by more than four hundred million dollars.” In early June, a ruling from the judge on post-trial motions affirmed the jury’s verdict in all material ways, but ruled for Cox on one legal issue that will trim the total number of works in the suit (and thus total damage figure). The judge gave Cox sixty days to submit a new list of works that accounts for overlap between copyright protections for sound recordings and their underlying musical compositions.

Multiple emails seeking further comment from both Cox and the defendant’s lead trial counsel at Winston & Strawn went unanswered.

“This case sends a very loud message to ISPs and other technology companies that they can’t build a business that just tramples on and disrespects the rights of content and brand owners,” says Gould. “Eventually, you reach a point where you and the client take a different path toward addressing it.”

Now, there are plenty of reasons to go down that path, if need be. About a billion.