When the Jewish heirs to a fortune of Nazi-looted art thought they had nowhere else to turn, they found Nicholas M. O’Donnell ’03. The author of A Tragic Fate: Law and Ethics in the Battle Over Nazi-Looted Art (Ankerwycke 2017), with a proven track record in complex litigation, and renowned as an expert in art law, O’Donnell pressed their cause all the way to the Supreme Court.

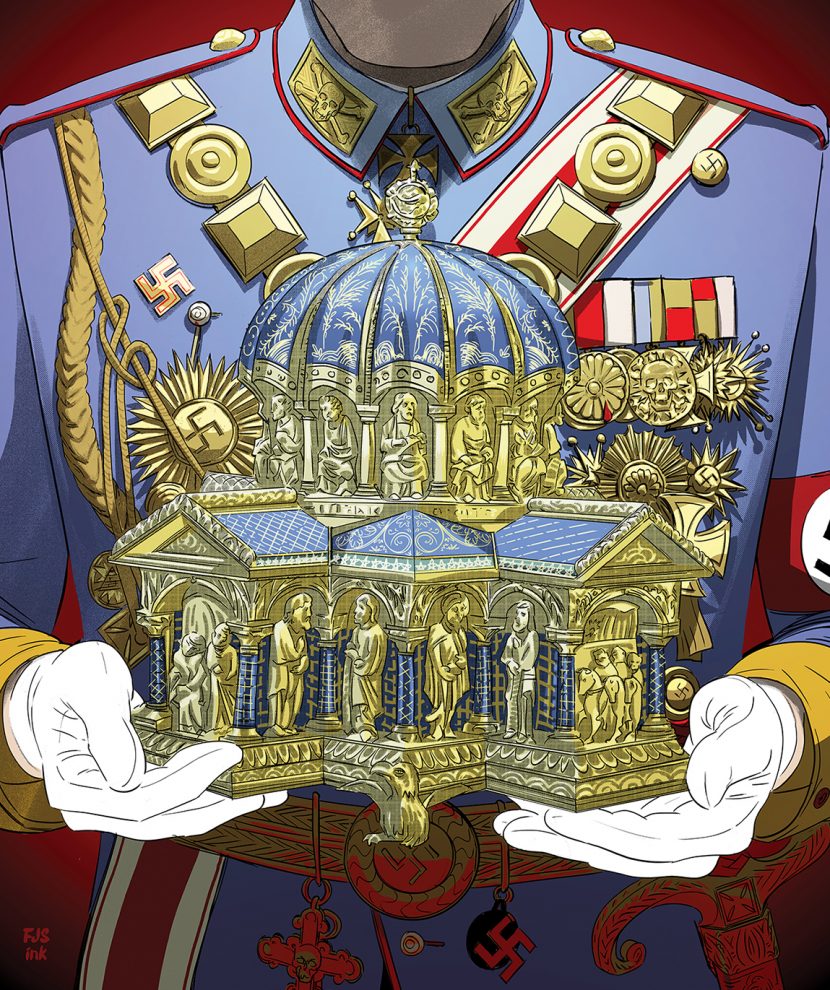

In dispute was the ownership of a portion of the Guelph Treasure, a collection of medieval Christian relics and reliquary held by Germany’s Prussian Cultural Heritage Foundation valued at $250 million. But O’Donnell’s case, Germany v. Phillip, came to stand for more than that. It revealed the limits of justice against the hard realities of foreign affairs. To critics including O’Donnell and some members of Congress, it also signaled a troubling willingness by Germany to revise difficult truths about the Holocaust.

Germany’s interest in the treasure is profound. Considered to be significant expressions of German art and culture, the Guelph Treasure, or Welfenschatz, was collected over the centuries by the Collegiate Church of St. Blaise, in Brunswick, before coming into the possession of the royal Guelph dynasty in 1671. In 1929, the Duke of Brunswick sold the treasure to J&S Goldschmidt, I. Rosenbaum, and ZM Hackenbroch, a consortium of Jewish art dealers from Germany and elsewhere. The consortium sold around half of the collection to museums and individuals in Europe and the US in the years before Hitler became German Chancellor on January 30, 1933.

What happened next was devastating.

By early spring of 1933, the Dachau concentration camp was already open. The Nazi government was organizing boycotts against Jewish businesses. Jewish art dealers were banned from plying their trade. The consortium members could not pursue their livelihood.

Hermann Goering, Hitler’s second-in-command, set his sights on the remaining unsold half of the Guelph Treasure. “Arguably the most notorious art looter in European history, Goering routinely went through the bizarre pretense of ‘negotiations’ with, and ‘purchases’ from, counterparties who had no ability to refuse to sell to him at the risk of their lives,” O’Donnell wrote in a brief. In 1935, “after two years of direct persecution and with no ability to sell their property on the market, the consortium had only one option left: the Nazis knocking on their door.”

The Nazis agreed to purchase the Guelph Treasure for a third of its value, but, O’Donnell wrote, “The consortium did not receive even that amount. Some [of it] was ‘paid’ in swaps of subpar art. The consortium was obligated to pay a ‘commission’ of 100,000 RM to the cabal that orchestrated the theft. After that, nearly a quarter of the transaction price was paid to a blocked account that the consortium could not access.” Goering presented the Guelph Treasure to Hitler as a gift. Meanwhile, two members of the consortium fled Germany, and one died at the hands of a Nazi mob.

Before they hired O’Donnell in 2014, the consortium members’ heirs—Gerald Stiebel and Jed Leiber of the United States, and Alan Philipp of the United Kingdom—sought restitution from the Prussian Cultural Heritage Foundation in 2008 on the grounds that their forebears were forced to sell the Guelph Treasure to the Nazis for a fraction of its value. The foundation refused. The purchase price was Depression-era market value, and the consortium was paid the fairly agreed-to price, the foundation said.

In 2012, the heirs appealed to a German government agency established in 2003, known as the Advisory Commission for the Return of Cultural Property Seized as a Result of Nazi Persecution, Especially Jewish Property. Commissions like this exist throughout Europe, and they are not without controversy, according to Leila Amineddoleh ’06, an expert in art and cultural heritage law and founder of Amineddoleh & Associates LLC in New York City. “Some of these organizations have been accused of being complicit in not returning property because it might benefit the nation itself. You might imagine that a German government agency might not be that enthusiastic about returning property of such great value,” Amineddoleh says, although she expresses no opinion on the legitimacy of the Guelph Treasure’s ownership transfer.

The Advisory Commission rejected the heirs’ claim. “Although the commission is aware of the difficult fate of the art dealers and of their persecution during the Nazi period, there is no indication…that points to the art dealers and their business partners having been pressured during negotiations,” the commission concluded. “In the end, both sides agreed on a purchase price that was below the 1929 purchase price, but which reflected the situation on the art market after the world economic crisis.”

O’Donnell, who studied art history at Williams College and once worked at the Clark Art Institute in Williamstown, Massachusetts, where one of his tasks was to comb through the collection in search of Nazi-looted art (none turned up), finds the German government’s stance galling. After all, the Jewish art dealers were “negotiating”… with the eventual architects of the Final Solution. To call it a fair deal—“That’s outrageous. It’s disgusting,” O’Donnell says. “And I get frustrated at those who lob accolades at the [foundation], like the funding it provides and the cocktail parties that it throws, who won’t speak about how outrageous this is. It didn’t have to come to this. They have been obstinate and arrogant and revisionist, and I have no patience for it.”

In 2015, with no ability to appeal the commission’s recommendation to the courts of Germany (the statute of limitations had expired), and no international courts to turn to, O’Donnell, a partner at the Boston firm Sullivan & Worcester, filed a lawsuit for restitution of $250 million on behalf of the heirs in federal district court in DC.

The fate of the case turned not on the facts, but on the question of jurisdiction. That’s because the heirs were trying to sue in a US court the sovereign state of Germany and a German state agency over the disposition of property once owned by (arguably—we’ll get to that later) German nationals.

Here is what O’Donnell was up against: Under the Foreign Sovereign Immunities Act (FSIA) of 1976, a foreign government cannot be sued in US court unless some very specific exceptions apply. That’s called sovereign immunity. “There’s a very heavy thumb on the scale to refrain from adjudicating these cases because they create separation of powers problems,” says BC Law Professor David Wirth, an expert in foreign relations. In the United States, the President is responsible for conducting foreign affairs. If a US court reaches a diplomatically problematic ruling, Wirth says, “the President is the one who has to take the heat, so to speak. And under our constitutional structure, there isn’t always a lot he can do in response to a complaint from a foreign government about a court order.”

To persuade a US court to exercise jurisdiction over Germany, O’Donnell needed to articulate an exception to the rule of sovereign immunity. Creatively, and compellingly, he zeroed in on § 1605(a)(3) of the FSIA, which reads in part: A foreign state shall not be immune from the jurisdiction of courts of the United States…in any case…in which rights in property taken in violation of international law are in issue….

“There is no more quintessential taking of property in violation of international law,” O’Donnell reasoned, “than the Nazis’ twelve-year international art-looting spree.”

O’Donnell’s argument distills down to this: The forced sale of the Guelph Treasure was part of the Nazis’ genocidal project against the Jewish people, where economic deprivation was intentionally life-threatening and ultimately fatal. Genocide violates international law. Therefore, the Nazis’ taking of the Guelph Treasure satisfies the “in violation of international law” exception to sovereign immunity, and US courts can exercise jurisdiction over Germany.

Germany in essence argued that US courts had no business adjudicating this case because of something called the domestic takings rule: when, as in Philipp, a government takes property from its own nationals, the case is a domestic matter and not a matter of international law. Germany sought to have the case dismissed.

According to Professor Wirth, O’Donnell was arguing that the phrase “in violation of international law” in § 1605(a)(3) encompasses the international prohibition on genocide. Germany, in contrast, grounded its argument in customary international law—the tacit way that, over time, foreign nations have come to deal with one another. Imagine, for example, ATMs. There is no written law saying that we must stand several paces back from the person at the machine, but we all do so because, when it’s our turn at the ATM, we don’t want someone looking over our shoulder.

“Custom is an implied interaction that everyone abides by because they want those customs to apply to themselves as well,” Wirth says. In foreign relations, he explains, “there’s a formula for determining it. The formula is a pattern and practice of states motivated by a sense of legal obligation. And the difference from the ATMs is that it’s binding law.” The domestic takings rule invoked by Germany—that a nation does not get involved when a foreign government takes property from the foreign government’s own nationals—is the custom, Wirth says.

O’Donnell’s jurisdiction argument won in both the district court and before a panel of the DC Circuit Court of Appeals. After the appeals court rejected Germany’s request for an en banc hearing, Germany turned to the Supreme Court, and the Court took up the case. At the Court’s invitation, the US Solicitor General filed an amicus brief; the Solicitor General urged the Court to reject O’Donnell’s reading of § 1605(a)(3).

At oral argument on December 7, 2020, counsel for Germany acknowledged, “if a country is taking property with the intent of physically destroying a people or a part of a people, it’s unquestionably a genocidal act.” So, if property can be taken as an act of genocide, and genocide is a violation of international law, Justice Kagan asked, “why doesn’t that just solve the problem?” Counsel for Germany answered, “I think the question is what’s the gravamen” of § 1605(a)(3). Section 1605(a)(3), he said, is not about genocide. It is about the taking of property.

O’Donnell, for his part, had to contend with the Justices’ concerns about the limits of his legal theory. Justice Barrett worried that the federal judiciary would wind up inundated with genocidal theft claims from abroad.

O’Donnell replied, “I think the limiting principle, Justice Barrett, remains the taking itself: What was the property taken in violation of international law?”

On February 3, 2021, Chief Justice Roberts delivered the opinion of the Court. The Court concluded that the law had evolved to permit jurisdiction over cases involving American-owned property taken by foreign nations. But, the Court said, the rise of international human rights law and the law of genocide notwithstanding, the law had never abandoned the domestic takings rule. In other words, cases involving a foreign government’s taking of the property of its own nationals are not matters of international law.

The Jewish art dealers [who owned the Guelph Treasure] were “negotiating”… with the eventual architects of the Final Solution. To call it a fair deal—“That’s outrageous. It’s disgusting.”

Nicholas O’Donnell ’03

The Court then turned to the do-unto-others sensibility of customary international law: “We have recognized that ‘United States law governs domestically but does not rule the world.’” … “We interpret the FSIA as we do other statutes affecting international relations: to avoid, where possible, ‘producing friction in our relations with [other] nations and leading some to reciprocate by granting their courts permission to embroil the United States in expensive and difficult litigation.’” … “As a Nation, we would be surprised—and might even initiate reciprocal action—if a court in Germany adjudicated claims by Americans that they were entitled to hundreds of millions of dollars because of human rights violations committed by the United States Government years ago.”

In the end, the Court rejected O’Donnell’s argument, in effect ruling that FSIA’s “in violation of international law” exception does not encompass genocidal theft when the dispute involves property taken by a foreign nation from its own nationals.

What if the members of the consortium were not German nationals at the time the Nazis took the Guelph Treasure? On this point, the Court remanded the case to the lower courts for further consideration.

The decision was unanimous.

Both David Wirth and Leila Amineddoleh agree that the Supreme Court properly applied the FSIA in Philipp. But O’Donnell says, “I think this decision plunges its head in the sand in a way that is really upsetting.” He plans to address the nationality question on remand

Beyond the legal wrangling, O’Donnell flags a different concern: that to reach the conclusion that the Nazis’ acquisition of the Guelph Treasure was not a forced sale, Germany implicitly had to deny, or at least downplay, the perilous situation of the Jewish art dealers in 1934 and 1935. “What’s very frustrating about the German-language coverage of this case is it treats the recommendation of the Advisory Commission as determinative of the historical facts,” O’Donnell says. “I have a lot more respect for people who said, I understand that your clients were victimized, but this isn’t a good way to line up the jurisdictions of different court systems.”

He is not alone. In October 2020, eighteen members of Congress wrote in a letter to the German ambassador: “Your government seems to be arguing that forced sales of art to the Nazi regime do not constitute takings at all and that the definition of genocide does not include what happened with respect to the full elimination of Jews from German economic life starting in 1933 when Adolph Hitler and the Nazi regime took complete control…. This is deeply concerning.” A smaller group of Congress members told the US Solicitor General that his support of Germany’s claim “is antithetical to American policy and values.”

What happens next is anyone’s guess. But whatever the eventual outcome, these words of Nicholas O’Donnell capture the sorrow of Germany v. Philipp: “I certainly wish it hadn’t come to this. I wish my clients had been successful in reaching some kind of resolution before they ever hired me.”