New developments in the landmark legal battle between Big Oil and the Standing Rock Sioux, already half a decade old, have given the tribe hope that the Dakota Access Pipeline’s days may be numbered—removing threats to tribal members’ treaty rights and water supply. But whatever the outcome of the tribe’s lawsuit, it won’t likely end the longstanding record of environmental racism in America.

In a 2017 cover story about the case in BC Law Magazine, Earthjustice’s Jan Hasselman ’97, attorney for the Standing Rock Sioux, observed that because of the North Dakota debacle “the whole country, the whole world, gained insight into how things have been going for people there, and why the grievances that arise from these historic injustices remain very real.”

Hasselman’s interest in environmental justice—the equal sharing of the burdens of pollution across races and economic classes—dates back to a decision he made years ago. “I had been working for Greenpeace and other activist groups, and I decided I would rather sue the bad guys than protest them,” he says of the resolve that led him to Boston College Law School and the classroom of Professor Zygmunt Plater. “It was a great decision; Zyg was a wonderful mentor and teacher.”

Plater’s teachings on environmental justice have influenced generations of lawyers. “Low political power is a magnet for toxics,” the professor says, a classic Plater-ism. “No wealthy community is going to stand by without lawyering up” against any project that threatens to pollute its air or water. It’s one of many painful truths that BC Law, its faculty—Plater and international environmentalist Professor David Wirth among them—and scores of graduates have endeavored for decades to rectify.

Recently, they’ve been joined in their efforts by University-wide collaborators, including Laura Steinberg, director of Boston College’s Schiller Institute for Integrated Science and Society. Steinberg, an environmental engineer, is leading an interdisciplinary effort to plot the origins and effects of environmental racism, find ways to combat it, and provide a platform for expert voices.

In short, Boston College, including BC Law, has made itself a center of both thinking and action on environmental justice. This is how that happened.

Environmental justice, or the lack of it, first grabbed headlines in 1982, when the siting in a Black-majority county of a dump for PCB-contaminated dirt drew massive protests. Prompted by the actions, a General Services Administration study found that “three out of four hazardous waste landfills examined were located in communities where African Americans made up at least 26 percent of the population, and whose family incomes were below the poverty level,” according to an EPA history of environmental justice.

An environmental justice movement took off, albeit slowly, through the 1980s and 1990s, years that saw additional damning studies, the passage of a handful of state environmental justice laws, and the founding of the EPA’s environmental justice office.

BC Law School played a large though unheralded role in those early years, thanks in large part to Plater, one of the first environmental lawyers to understand the importance of environmental justice to the field.

Plater, who in the late 1970s argued the landmark snail darter case before the US Supreme Court, points out that it involved more than an endangered species of fish. The same hydroelectric dam that could have meant curtains for the snail darter also threatened poor farmers and Cherokee Indian communities.

Some years later, Plater headed the legal team for the Alaska state commission that investigated the 1989 Exxon Valdez oil spill. Though media coverage of that disaster tended to focus on oil-covered beaches, Plater says it was “fishermen who got hit the hardest, including [Native Alaskan] subsistence fishermen whose fishing rights had been hammered by the oil spill.” He adds that you can “scratch away at almost any environmental controversy, and you’ll be dealing with questions of democratic governance. And to be democratic, governance must incorporate consideration for segments of the population that have long been ignored.”

In 1996, the second edition of Plater’s widely adopted Environmental Policy: Nature, Law, and Society brought this truth to light, becoming the first casebook with a unit on environmental justice. Later editions have beefed up environmental justice content, and in a forthcoming edition, edited by Plater and Wirth, environmental justice is woven throughout the book, Plater says. One feature of the new edition is a role play in which students act the parts of disputants in a toxic waste dump siting case. “It’s important,” he says, “that students with no experience of the powerless communities that so often get hit by pollution get to see something that would otherwise be invisible to them.”

If hyper-polluting facilities and superfluous fossil fuel infrastructure can’t be built in working class communities or communities of color, they will have a hard time getting built anywhere.

Also in the 1990s, the Law School housed the world’s first environmental justice law firm, the nonprofit Alternatives for Community and the Environment (ACE). ACE had grant funding to cover the salaries of two lawyers, William Shutkin and Charles Lord, but no money for office space. They found their way to BC Law and, with Plater’s help, set up shop there. In return, Lord and Shutkin taught a class in environmental justice law. After three years, ACE acquired office space in Roxbury, the heart of Boston’s Black community, but they also retained their East Wing office.

During its five years at BC Law, ACE brought actions against an asphalt plant proposed for South Bay—between Roxbury and white, working-class South Boston—and an EPA plan to dump toxic sediment in downtown New Bedford, a blue collar fishing community. And in a series of lawsuits ACE forced property owners and Boston city government to clean up illegal garbage dumps. Lord still recalls the view from a client’s Roxbury apartment: piles of rotting garbage.

Escamilla v. Asarco, Inc. (1993), a seminal environmental justice case featured in early editions of Plater’s casebook, also had a BC Law connection: Susan Reardan O’Neill ’83, Plater’s former student, was in charge of motions and legal research for the plaintiffs. The case pitted residents of Globeville, a majority-Hispanic section of Denver, against the owner of a smelter whose emissions had contaminated Globe-ville’s soil with assorted toxic metals. Other polluting industries in Globeville included a creosote treatment plant and a dump for biomedical waste. In a 2013 oral history, lead plaintiff Margaret Escamilla channeled powerful outsiders’ attitude toward the neighborhood when she said, “This is Globeville, and we can do anything we want here.”

The daughter of a civil rights attorney mother, O’Neill arrived at BC Law with a well-developed passion for social justice and the public interest, a passion further stoked by her studies at the Law School. “Throughout my time there,” she says, “I felt there was a common goal, and that was to serve the common good.” With such a background, she was an awkward fit for her first job out of law school, with a firm that defended environmental claims against Big Oil. “There were questionable tactics and a callousness of the clients towards people they harmed. The lawyers directing my work were willing to bend the truth,” she says.

But in her second legal job, representing the plaintiffs in Escamilla, the Big Oil background proved useful. “I knew exactly what to expect in terms of summary judgment motions and motions to dismiss,” she says, “so I knew how to defend against them.” She defeated all attempts to get the case thrown out.

One defense motion that did succeed prevented plaintiffs’ lawyers from uttering the words “environmental racism” in court. Macon Cowles, lead attorney for the plaintiffs, devised a workaround, making sure that at least a dozen Globeville residents showed up in court each day. “The jury could very much see who they were,” he says, “and jurors noticed the contrast between them and the lawyers and others in the courtroom: bespoke, well-dressed men, and women in high heels.”

Housing prices in Globeville—$35,000 on average back then for a single family residence—presented an even tougher challenge, severely limiting damages for loss of property value. In another workaround, the plaintiffs asked for money to remediate the properties, a vastly more expensive proposition. “Unless there was something special about the property, such higher damages for restoration of the property were not recoverable,” Cowles recalls. “Our job was to argue … that one’s home has that special character.” The argument succeeded, to the tune of $28 million in restoration damages, the biggest environmental verdict in Colorado history at the time. As important as the cleanup itself, says Cowles, was the “huge affirmation for that community in that they’d stood up for their rights and been vindicated by the law.”

In 2021, environmental justice looms far larger in the public consciousness than it did in the days of Escamilla, but Plater’s formula still applies: Communities are likely to attract pollution in inverse proportion to their wealth and power.

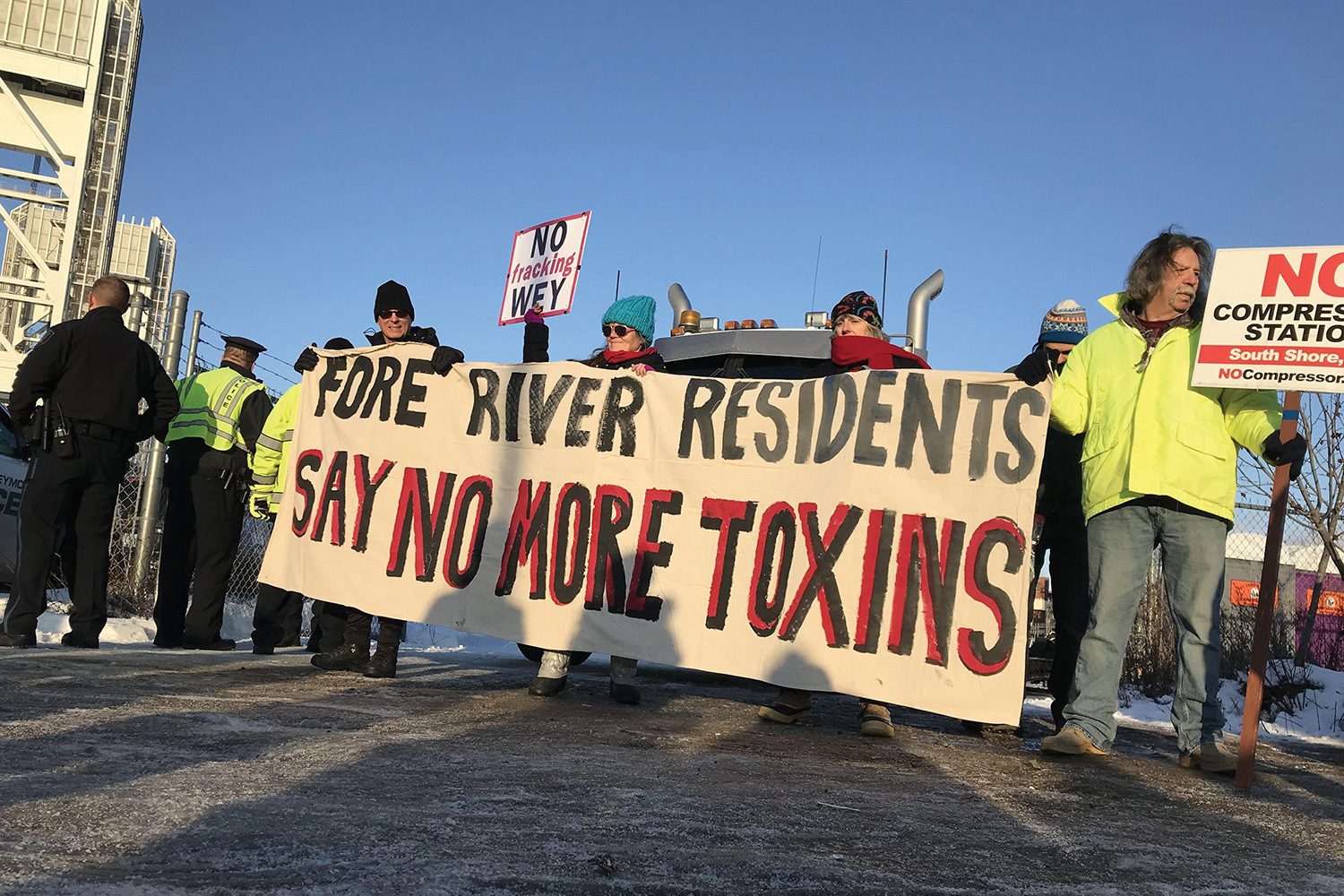

The ongoing fight against the Fore River Compressor Station, in Massachusetts, is a case in point. The compressor, an enormous gas-powered pump that helps move natural gas from Pennsylvania along a pipeline that extends up to Canada, is sited near blue collar neighborhoods of Quincy and Weymouth that already face pollution from a tank farm, a state highway, an electric power plant, a chemical plant, and a plant that converts the region’s sewage sludge into fertilizer.

So when the state declared that toxic emissions from the compressor station—exhaust from the compressor and methane from periodic “blowdowns”—wouldn’t exceed permissible limits, it was ignoring the compressor’s cumulative impact, the sum of its emissions and those from preexisting facilities. In a neighborhood with multiple pollution sources, as Plater says, “People don’t breathe the pollution from just one source; they breathe the pollution from all of them.”

Michael Hayden ’04, a partner at Morrison Mahoney in Boston who represents compressor station opponents, has had his hands full for years with litigation at the Federal Energy Regulatory Commission (FERC), assorted state environmental departments, and the federal and Massachusetts courts. “It’s unbelievable,” he says, “how many parallel actions and appeals are going on simultaneously.” The plaintiffs have included a neighborhood activist group, Quincy city government, and until recently, the town of Weymouth.

Then in November, the town accepted $10 million from Enbridge, the pipeline operator, in return for withdrawing from the lawsuit. This kind of buyoff isn’t rare in environmental justice fights. “Very often communities are trading off their health for money,” says Plater, “and you can imagine how that rips apart communities.”

Despite fierce opposition from neighbors and local officeholders, the compressor station easily obtained its state permits, thanks in part to behind-the-scenes help from Governor Charlie Baker, according to an investigative article in the December 12 Boston Globe. Professor Philip Landrigan, MD, director of the Global Pollution Observatory at BC’s Schiller Institute, who testified before the Massachusetts Department of Environmental Protection about the compressor’s likely effects on children’s health, faults Baker for his closeness to fossil fuel interests.

Permits from the industry-friendly FERC also came easy. Then, this February, FERC issued an order inviting briefs on whether the commission should reconsider the operating permit. Such an action by FERC is virtually unheard of, Hayden says. Significantly, the term environmental justice appears in FERC’s order no fewer than a dozen times.

Hayden’s brief, submitted to FERC in April, argues that the compressor station, near densely settled neighborhoods and a heavily traveled four-lane bridge, poses a fire and explosion risk; that demand for natural gas has dropped rapidly as solar and wind replace gas-powered electric generation; and that three emergency shutdowns since September 2020 show that Enbridge, the compressor station’s owner, cannot operate it safely.

“Scratch away at almost any environmental controversy, and you’ll be dealing with questions of democratic governance. And to be democratic, governance must incorporate consideration for segments of the population that have long been ignored.” —Environmental Law Professor Zygmunt Plater

Whether or not FERC rescinds the permit, the compressor station fight has produced a victory for environmental justice. Early this year, the Massachusetts legislature enacted a sweeping environmental law with several environmental justice provisions, including one that requires state agencies to weigh cumulative impact when making permitting decisions.

Like FERC’s order in the fore river case, the recent order to shut down the Dakota Access Pipeline took seasoned observers aback. Courts and federal agencies don’t even think about shutting down key energy infrastructure—or they didn’t until recently.

The fight against the pipeline dates back to a fateful decision by the Army Corps of Engineers. In initial plans the pipeline crossed the Missouri River just north of Bismarck, North Dakota’s capital, a well-off, mainly white municipality. But the corps nixed that routing because it threatened the city’s water supply.

That the corps instead approved a route that threatens a water source that serves low-income indigenous people is “a textbook case of environmental racism,” says Hasselman, of Earthjustice. In 2016, the corps nearly admitted that, ordering a halt to pipeline construction because, it said in a press release, “additional discussion and analysis are warranted in light of the history of the Great Sioux Nation’s dispossessions of lands [and] the importance of [the river] to the Tribe.”

Any discussions ended with the advent of the Trump administration, which let construction resume. In summer 2017, the crude started flowing, but the plaintiffs persisted, bombarding both the courts and the corps with motions.

From Plater, Hasselman says he learned that lawyers must distill the facts and the law “into a compelling narrative, not just for the courts but the public as well.” For the pipeline case his narrative goes as follows: The pipeline threatens not just a vital water source but also fishing and hunting grounds that tribe members count on for subsistence.

This David-v.-Goliath story brought extensive media coverage, and then a decision called “shocking” by the pipeline operator. In July 2020 Judge James Boasberg of the US District Court in Washington, DC, ordered the corps to come up with an Environmental Impact Statement (EIS) for the pipeline, a far more detailed and time-consuming process than the cursory study the corps had performed before construction; in the meantime he ordered the pipeline shut down. The US Appeals Court for the DC Circuit stayed, and eventually overturned, the part of the order that called for a shutdown, but over the protests of the pipeline operator, they sustained the part requiring an EIS.

The coming of another administration earlier this year raised plaintiffs’ hopes that the Corps of Engineers itself would shut the pipeline down without further prompting from the court, but those hopes have been dashed. In April, the corps endorsed the pipeline’s continued operation. Rhetoric from the Biden Administration “has been phenomenal,” comments Hasselman, “but this was an early test of their seriousness, and they came up short. It remains to be seen whether their commitment to environmental justice is serious or just talk.”

The unprecedented moves by the federal courts and FERC in the Weymouth and Dakota Access cases, as well as the new Massachusetts law, reflect a national upsurge of interest in environmental justice. Programming at Boston College has also reflected a growing interest in the topic. The Clough Center for the Study of Constitutional Democracy, the Forum on Racial Justice in America, and the Rappaport Center for Law and Public Policy, as well as the Schiller Institute, have hosted no fewer than eight lectures and panels on environmental justice in the past year alone.

BC Law’s Wirth, for instance, invited Barry Hill, an early director of the EPA’s Office of Environmental Justice, to take part in Clough’s climate constitutionalism speaker series. “He spoke about the impacts and implications of both climate [change] and racial reckonings for communities of color in the United States and abroad,” Wirth says. In a recent Schiller presentation, Steinberg alluded to comments made by “the father of environmental justice” Robert Bullard, who decried the damage done to Black communities by longtime discriminatory zoning, leaving them particularly vulnerable to the ravages of Covid-19.

Meanwhile, after having neglected the topic for years, old-line environmental groups are lining up behind the new push for environmental justice, having finally understood that without it there will never be a healthy environment—for anyone.

“If pockets of the population are disproportionally exposed to toxic chemicals, then there’s no way the total population’s exposure can be brought down within acceptable limits,” explains the Schiller Center’s Landrigan. “Airborne toxics carry on the wind; contaminated groundwater can travel underground and come up miles away.” Equally important, if hyper-polluting facilities and superfluous fossil fuel infrastructure can’t be built in working class communities or communities of color, they will have a hard time getting built anywhere. As Landrigan puts it, “You don’t see a lot of compressor stations being built in places like Weston or Wellesley.”