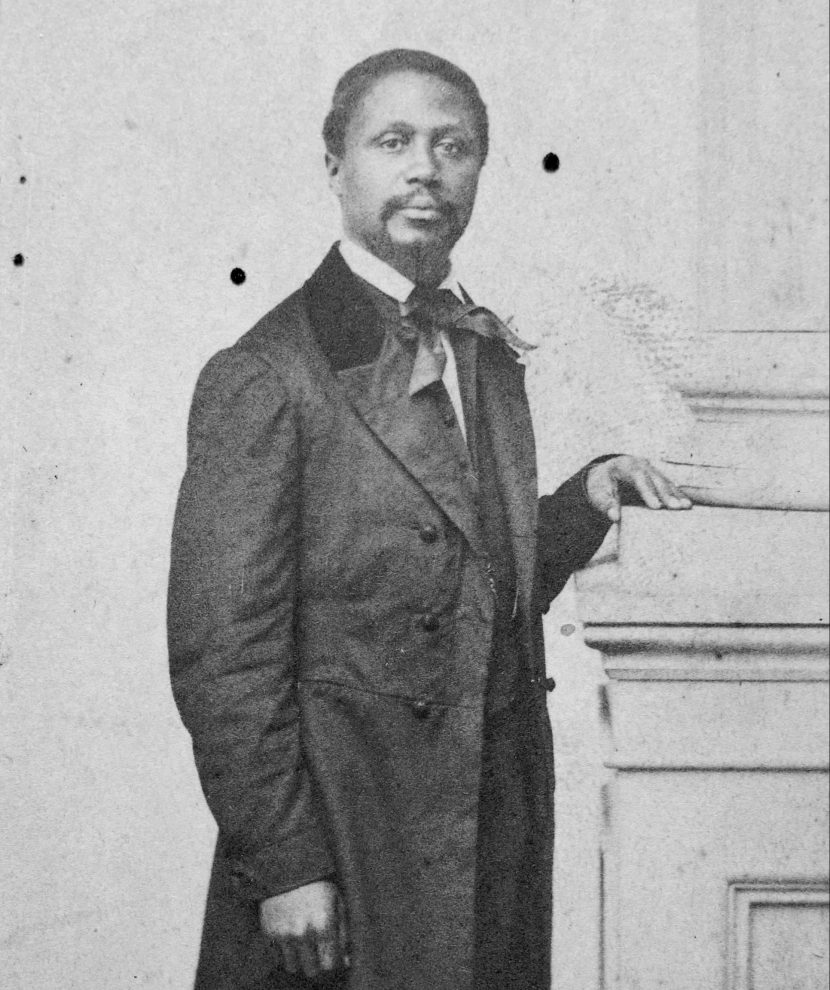

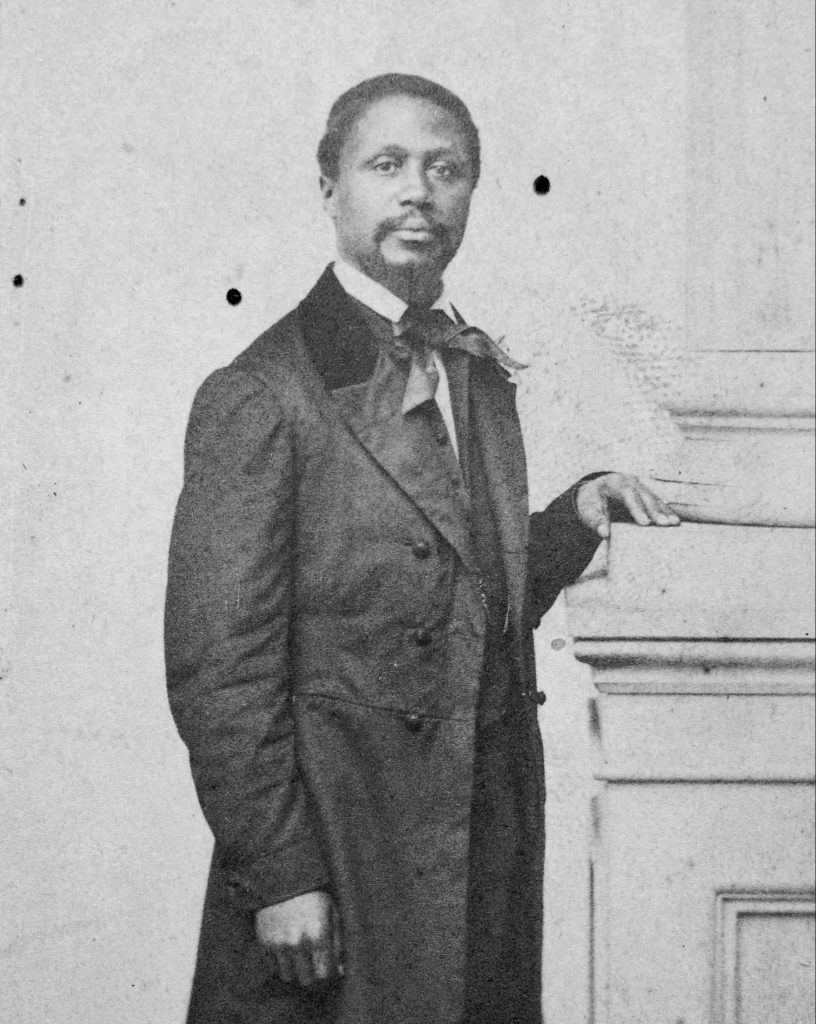

His should be a household name. He was the country’s second African American lawyer (1847) and first Black lawyer to argue a case at a jury trial (1848)—and he won. He filed a landmark lawsuit to integrate Boston’s public schools (1848) and was co-counsel with Charles Sumner on the appeal (1850), a goal ultimately attained through an act of the Massachusetts legislature (1855). He almost certainly arranged the daring courtroom escape of a refugee from slavery. He was a force in the anti-slavery and early civil rights movement, alongside Frederick Douglass, William Lloyd Garrison, and Underground Railroad conductor Harriet Bell Hayden. He fought for the unheard-of commissioning of Black officers during the Civil War. He was a trusted criminal defense lawyer to members of Boston’s Irish community. His gift of his substantial personal library to Boston College—the only extant antebellum library of an African American besides Frederick Douglass—significantly expanded the foundational holdings of the then-fledgling institution.

His name was Robert Morris. And too many of us have never heard of him.

Boston College Law School Legal Information Librarian Laurel Davis and Professor Mary Sarah Bilder are intent on changing that. Their recent research into Morris has unearthed new insights into Boston history and the origins of Boston College. And their determination to bring Morris’s story to the wider public has yielded a lively new website that spotlights this prominent individual and the times he helped to shape.

“The books [at BC] looked ragged and worn, and there were no law books. It was such a classic case of not judging a book by its cover, literally, because there was such a story there and it took us a while to see it.”

Legal Information Librarian Laurel Davis

The grandson of Cumono, a formerly enslaved man, Robert Morris was born in 1825 in Salem, Massachusetts. Like his father, Morris worked as a waiter in private homes until, through that work, he met Boston attorney Ellis Gray Loring, who hired him as a copyist and mentored him in the practice of law. Morris was admitted to the bar in 1847. He converted to Catholicism, the religion of his wife Catharine, in 1870, and passed away at the age of 57 on December 12, 1882. His son, Robert and Catharine’s only surviving child, died two weeks later.

Throughout his life, Morris collected books; his original library likely numbered in the hundreds. We know from the historical record that many of his books were donated to Boston College, perhaps in two installments: first in 1882, and then in 1895, when Catharine died at age seventy and her estate, which likely included more of Robert’s books, was bequeathed to the Church of the Immaculate Conception, the church of Boston College, then in Boston’s South End.

More than a century later, in 2007, two librarians at BC High School, Tia Esposito and Anna Stephens, received an intriguing query: Why was this Black 19th century Boston attorney known as “The Irish Lawyer”? Their quest for an answer took them on a five-year journey that culminated in them identifying many of Morris’s extant books at Boston College. (The discoveries continue: Two of Morris’s books were found last summer in the law library’s Daniel R. Coquillette Rare Book Room.) So far, eighty-six books have been identified in the BC library system. They feature works by poets, essayists, scientists, and historians, and display Morris’s keen interest in abolitionism, Africa, and the African diaspora.

As an American legal historian, Professor Bilder knew of Robert Morris, and had been teaching about him in her classes. In 2016, she became aware through a blog post that BC held his books, and she and Laurel Davis went to the Burns Library to look at them. At first, they felt “a little crestfallen,” Davis says. “The books looked ragged and worn, and there were no law books.” It turned out, however, to be “such a classic case of not judging a book by its cover, literally, because there was such a story there and it took us a while to see it.”

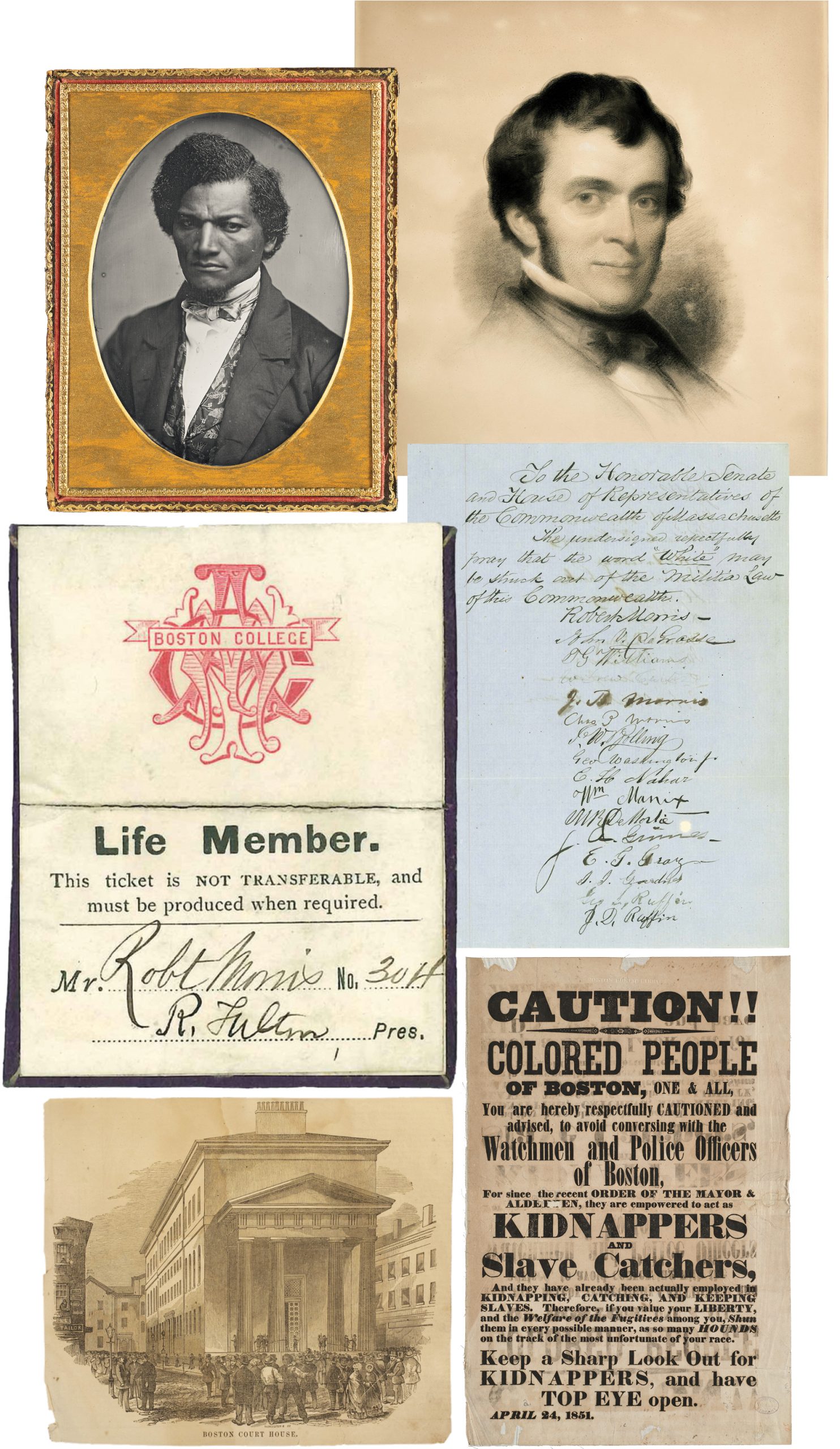

Within that story was a mystery: How did BC wind up with Morris’s library? Was it just happenstance? While going through Morris’s papers at the Boston Athenaeum, Davis and Bilder hit pay dirt. “We opened a folder,” Davis says, “and there was his Boston College YMCA card, and we just looked at each other and said, he had a real connection to BC!” The card, they realized, was a clue that Morris’s gift of his library to the school was not just casual. It was motivated by his deep involvement with, and membership in, the BC community.

And that led to a wider epiphany. “He knew the early founders of Boston College,” Bilder says. “He was the lawyer for the Irish in Boston. That is an important addition to a conventional narrative we sometimes hear about Irish/Black relations in Boston.”

Bilder and Davis curated their research into an exhibit that was on view in the law library’s rare book room in 2017, and they co-authored a sparkling narrative of Morris’s life as revealed by his books for the Law Library Journal. But they were not satisfied leaving Morris’s story to specialists and those-in-the-know. They started talking about a website, for which they tapped the expertise of BC Law’s Digital Initiatives & Scholarly Communication Librarian Nick Szydlowski (now at San Jose State University) and Digital Initiatives & Scholarly Communication Specialist Abraham (Avi) Bauer (now the interim holder of Szydlowski’s position).

“We believe that his unfound law books are out there somewhere. One of our greatest hopes is that they come to light.”

BC Law Professor Mary Sarah Bilder

After a year of intense collaboration and creative development, the website was launched on November 12, 2021, the 170th anniversary of Morris’s acquittal on charges of violating the Fugitive Slave Act of 1850. Perhaps best described as a digital exhibit, it is a welcoming masterwork meant for everyone, yet intentionally calibrated for high school and college students. It explores the many vectors of Robert Morris’s life, the Boston that he lived in, the people in his circle, and the energy of the abolitionist and civil rights movement of his time. It’s rich with images of primary sources, including a photo of Morris’s son, Morris’s petition to integrate the Massachusetts Militia, the legal writ he filed in the school desegregation case Roberts v. City of Boston, the 1853 petition he signed demanding full rights for women, and, of course, the ticket granting Morris life membership at the BC YMCA.

“We ended up telling the story, I think, in three ways,” Bauer says. “One is the main narrative of the website, one is temporally focused through a timeline, and the other is a spatial narrative on the StoryMap.” The StoryMap, which pinpoints important locations on an 1852 map of Boston, is notably compelling. It pierces Morris’s story in a way that narrative alone does not. When, for example, you trace the long walk to school of Sarah Roberts, Morris’s five-year-old client who was prohibited from attending the all-white school near her home, you feel the sting of injustice. And when you see exactly where Morris was spotted along the escape route of his client Shadrach Minkins, a refugee from slavery, you might just raise an eyebrow. “The Shadrach Minkins story is a very critical narrative to Robert Morris’s story, and on the map, you actually see the events happening on a few streets in Boston,” says Szydlowski. “It’s more visceral and evocative, I think, on the map than it is in the text.”

Bilder and Davis are certain that there is more about Morris awaiting discovery, including more of his books. “We believe that his unfound law books are out there somewhere. One of our greatest hopes is that they come to light, because we could then understand more about him as a lawyer,” Bilder says. And so, on the new website, knowing that it was his habit to sign each book in his beloved collection, Bilder and Davis have left a breadcrumb: an image of a bookplate with Morris’s signature. Perhaps, one day, somebody somewhere will recognize his signature inside a long-forgotten volume and open a new window into the remarkable life of Robert Morris.

To view the interactive website of Morris’s life story, visit bc.edu/robert-morris. To read about the prize that the AALL awarded to the Morris website creative team, click here.