In office hours, a student always gets my attention when mentioning an arts background. For such a student, I always pose the same question: How do you reconcile your legal and artistic sides?

I ask because I have not resolved this question. I am now a full-time law professor, but I have always been passionate about the arts: the plays of Aeschylus and Shakespeare, the prose of Gabriel Garcia Marquez and George Eliot, the music of Beethoven and The Beatles, or the films of Wong Kar-Wai and Denis Villeneuve. I play guitar and piano, and I sing. And I even dabble in artistic creation: For example, during Covid-19 lockdown, I took songwriting classes at Berklee College of Music. I’ve since written dozens of songs.

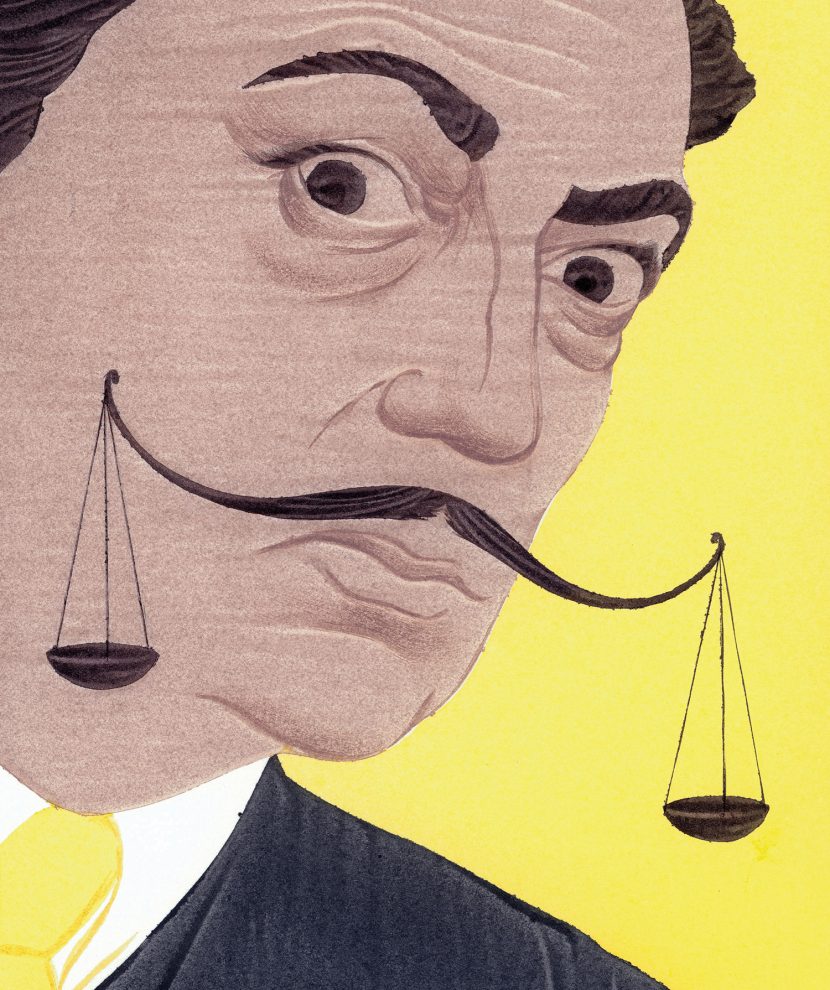

And yet, this artistic engagement often feels remote from my legal pursuits. At worst, they seem wildly contrasting. Whereas the greatest art appeals to our common humanity, law often focuses on technical argumentation and dispute resolution. In the face of art’s poetic beauty, law can feel decidedly prosaic.

An initial approach embraces the contrast: Perhaps coherence in one unitary self is illusory? We inevitably split our lives across many incongruent domains. I have interests in psychology, philosophy, and religion, but also train in CrossFit and Brazilian jiu-jitsu. I am American, but also ethnically Lebanese and Korean. I would like to integrate these aspects of myself whenever possible; interdisciplinary synergies are mutually beneficial and personally enriching. A second option blends art and law in one occupation, but I often find such intersection unsatisfactory. Attorneys in the music business, for example, engage with intellectual property questions that render the most stirring songs objects of adversarial dispute. And I disfavor art concerning law—the courtroom drama of Aeschylus’s Eumenides, for example, is my least favorite in the Oresteia trilogy.

A third possibility is the most common student response: something to the effect of “I find beauty in law,” citing powerful passages from 1L Constitutional Law. I do not disagree. But even the most soaring US Supreme Court dicta pale in comparison to the beauty we find in art. Compare any Trusts and Estates judicial opinion to majesty of this soliloquy from Shakespeare’s Richard II:

Let’s talk of graves, of worms, and epitaphs;

Make dust our paper and with rainy eyes

Write sorrow on the bosom of the earth,

Let’s choose executors and talk of wills:

And yet not so, for what can we bequeath

Save our deposed bodies to the ground?

For now, my best answer is that, perhaps, my years of artistic engagement have cultivated two distinct ways of apprehending the law.

First, transcendence. Once, I took a personality test that identified one of my central traits as “transcendence”—the appreciation of beauty and excellence. On some level, I view law as most transcendent when it is either international—aspiring to higher, universal ideals that emphasize common humanity irrespective of national boundaries—or theoretical—searching for elegant and profound conceptualizations of the more superficial disputes that animate more mundane legal doctrine.

And second, creation. On some level, the art of songwriting is not so dissimilar from the process of law review writing. Both are expressive enterprises, both are abstract, and both are oriented around discrete projects. Both derive from some spark of original idea, which must be diligently incubated over the lifespan of the subsequent composition. And, at their best, the novelty of both provides a sense of personal inspiration, energy, and meaning.