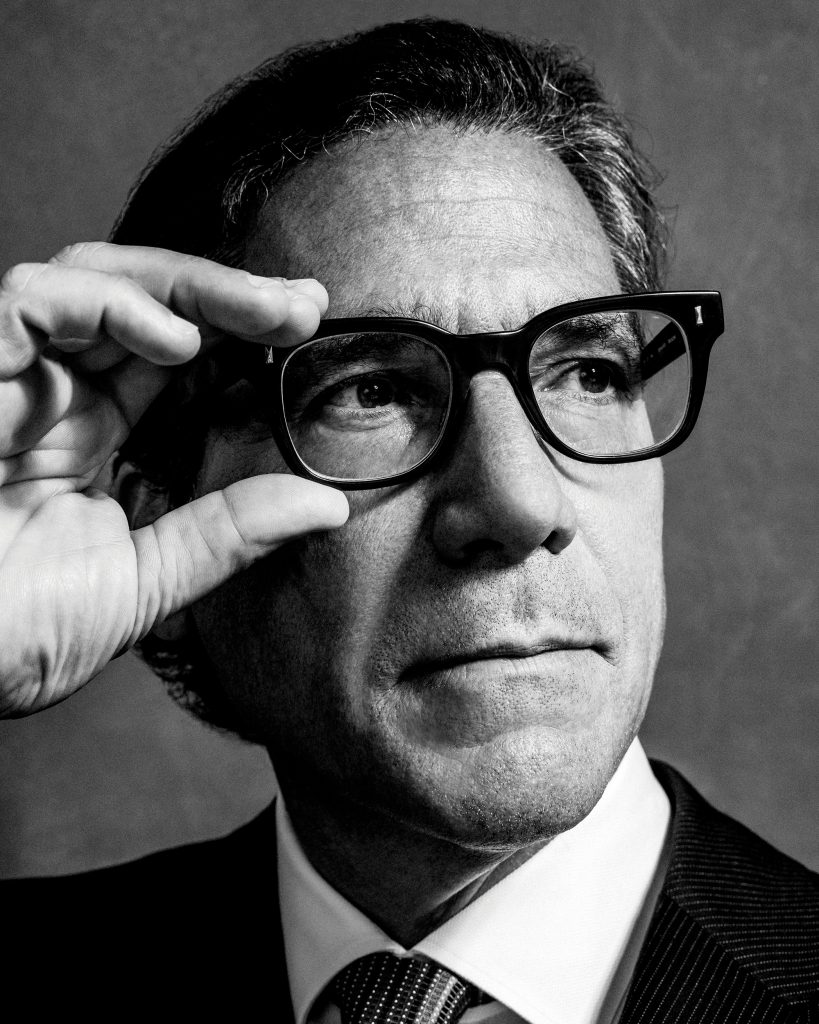

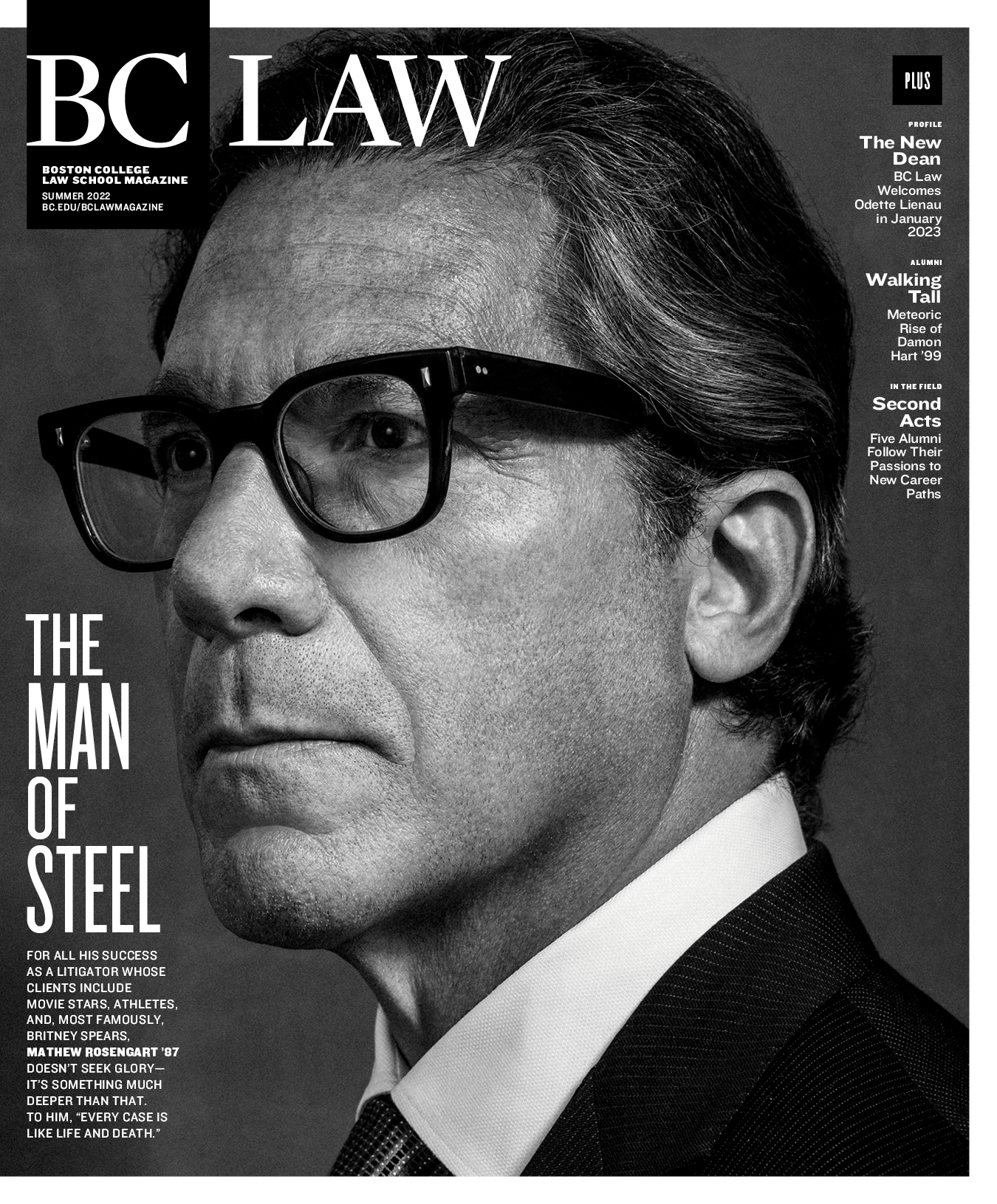

Even as a kid, Mathew Rosengart never could stomach seeing someone bullied. He remembers one incident in particular, when he was fourteen or fifteen and at summer camp in the Poconos. A group of about ten boys—friends of his—hatched a plan to wait until one of their bunkmates fell asleep so they could pick up his bed, carry it down to the lake, and leave it there so, Rosengart ’87 recalls, the boy would “wake up in a terror.”

Rosengart was adamantly against pranking the boy and tried to stop it. “Why pick on this kid?” he says. When darkness fell, he refused to participate as the plan was carried out amid whispers and snickers and great hilarity. “I didn’t find it fun like everybody else did.” The next morning, he sympathized with the bunkmate, who was “humiliated and on the verge of tears.”

It was one of the few times Rosengart has lost an argument. And though he has refined his persuasive skills since adolescence, that early impulse to champion the underdog has remained. “He is sure enough of his powers, and of his own value, that he doesn’t have to score off others,” former Supreme Court Justice David Souter wrote of Rosengart in a 1988 recommendation letter. “His object is to get where he has to go without pushing anyone else around more than he has to, without doing any needless damage to another person.”

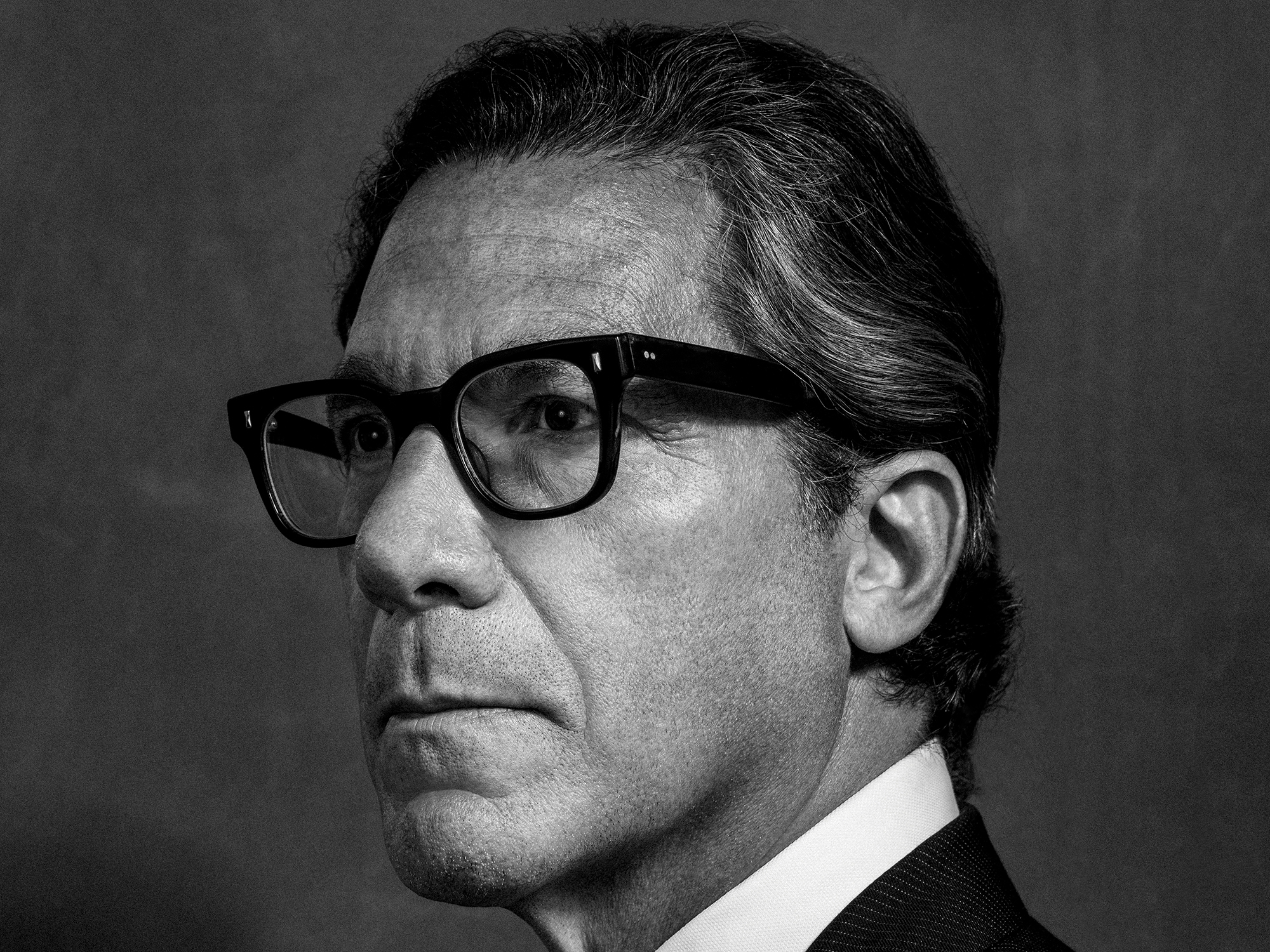

Along with an unrelenting work ethic and what Justice Souter called his “instinct” and “drive for thoroughness,” Rosengart’s personal integrity has brought him respect and kudos in the public sector, the corporate sphere, and among the sports and Hollywood elite and their fans. “He’s pretty uncompromising,” says director and screenwriter Kenneth Lonergan, whose 2016 film Manchester by the Sea won scores of prestigious awards, including an Oscar for best original screenplay. “He gets very worked up and indignant and seems ethically offended by the position his clients are in. He believes in what he’s doing.”

Most recently, Rosengart’s desire to do the right thing helped raise his profile to near-celebrity status when he handily won Britney Spears her freedom from a conservatorship that had allowed her father, Jamie Spears, control over her career, finances, and personal life for nearly fourteen years.

“He comes in, rolls up his sleeves, and performs something that most people, certainly Britney Spears, thought was miraculous. It’s not just a sign of raw intelligence, but also of commitment and devotion to the cause and laser focus.”

BC Law Professor Mark Brodin

“I feel ganged up on, I feel bullied, and I feel left out and alone,” the forty-year-old pop star said in June of 2021, in a probate hearing in which she asked the court’s permission to hire an attorney of her own choosing. Less than a month later, Rosengart had been retained and was striding up the steps of the Stanley Mosk Courthouse in Los Angeles past dozens of cameras and hundreds of pink-clad young men and women waving “Free Britney” posters and paraphernalia.

When he got back to the LA office of the powerhouse law firm Greenberg Traurig, which he joined in 2011, the CEO told him, “The case you are about to embark on is the biggest case in the country. No pressure.”

After a lengthy and contentious court hearing in late September 2021, Rosengart stood before microphones bearing the logos of CNN, ABC, the Associated Press, TMZ, and more than a dozen other outlets and announced, “Jamie Spears is no longer a conservator.” The crowd erupted into deafening whoops of joy that lasted nearly eight seconds, and fans intensified their adoration of Rosengart, who has Twitter accounts devoted to him, a Facebook fan club, an Instagram hashtag, several fancams, and nicknames like “Rosengod” and “Zaddy” (look it up). By mid-November, the entire conservatorship had been terminated, with a similar scene playing out. Rosengart admits the attention can be distracting, but says he succeeded by remaining, as always, resolutely focused on “the court, the law, and the client, doing my job, and shutting everything else out.” (Rosengart is still seeking legal redress from Jamie Spears for what the site Page Six described as a “laundry list of his alleged misconduct.”)

“Matt took on a case that had been stuck in the courts for years and within four months the conservatorship was over,” says Rosengart’s Boston College Law School mentor Mark Brodin, the Michael and Helen Lee Distinguished Scholar and a former Associate Dean for Academic Affairs. “He comes in, rolls up his sleeves, and performs something that most people, certainly Britney Spears, thought was miraculous. It’s not just a sign of raw intelligence, but also of commitment and devotion to the cause and laser focus.”

Growing up in affluent Lido Beach, Long Island, Rosengart was a star athlete who harbored dreams of becoming a professional ball player. He was at the center of a group of fifteen or twenty boys who rode their bikes around town all day and hung out at the basketball court or the Carvel stand on the beach, taking the train in to Manhattan for Knicks games and the occasional movie. His competitive streak showed itself early, according to his childhood friend Stewart “Bo” Berliner, now a radiologist in Waterbury, Connecticut. “We had this tough JV basketball coach, and Matt and I always felt like he didn’t give us enough playing time,” Berliner recalls. “In one game Matt really proved himself by scoring twenty-nine points, probably the highest point total of the season. It was like he was saying, ‘This is how good I am.’”

Berliner suspects Rosengart felt some competition on the home front, too, though he may not have been conscious of it at the time. “His brother Todd was three years older but he was valedictorian of his class and just brilliant, with almost perfect SAT scores,” Berliner says. While Matt’s bedroom was filled with National League pennants and sports memorabilia, Todd, today a heart surgeon and chair of surgery at Baylor College of Medicine, had anatomical posters and models lining his walls and shelves. Their mother, Berliner says, was “one of the prettiest ladies in the neighborhood,” and, to complete what Rosengart calls “a Norman Rockwell type of family,” their father was the well-respected town obstetrician.

“He is sure enough of his powers, and of his own value, that he doesn’t have to score off others.”

Former Supreme Court Justice David Souter

The boys’ idyllic childhood came to an abrupt end one day when Rosengart was just thirteen. He and Todd were called home from school after their father fell dead of a heart attack at age forty-six. “It was a very dramatic moment,” Todd says. “I came home and there were ambulances in front of the house. Matt got home about a half hour later, and I just remember grabbing him. That kind of stuff never happened in our world. It woke us up to the fact that bad things do happen.”

Rosengart admits that he “may be still grappling with” the incident. “No doubt my father’s death contributed to my drive, to being in the office at midnight if I have to and making sure every comma is in the right place,” he says. “Maybe I’m proving something to him or wanting him to be proud of me.”

As far as choosing law over medicine, “I wanted to carve my own path,” Rosengart says. Like many a young man in the 1960s, he developed “a romantic notion of being a courtroom lawyer” after reading To Kill a Mockingbird at fifteen, but it wasn’t until several years later that he seems to have really buckled down. After graduating from Tulane with a BA in social science, he enrolled at BC Law, where “he stood out as someone who was really going to make a mark in the profession,” according to Brodin. “He’s a very compelling person.”

Though Rosengart says he was “not an outstanding student,” he graduated cum laude and was gunning for a federal clerkship when a placement officer urged him to meet with Justice Souter, who was then on the New Hampshire Supreme Court and looking for a clerk from BC and one from Harvard. Rosengart agreed to the interview. “You know the feeling you get when you meet a celebrity?” he says. “How the molecules in the room sort of change when you’re in the presence of somebody great? I was very, very nervous and Justice Souter immediately put me at ease, as he does with everybody he meets, and we just hit it off.” They hit it off so well, in fact, that when their year in New Hampshire was over, rather than the typical goodbye lunch, Rosengart and his fellow law clerk arrived at Justice Souter’s house in a limousine to take him to his favorite Boston restaurant, Locke-Ober, for dinner after gin and tonics at the Ritz. “That started a tradition that later included annual hikes in the White Mountains and has gone on for about thirty years,” Rosengart says. He remains in close touch with Justice Souter and calls him a father figure.

In addition to making lifelong friends during that pivotal year, Rosengart solidified his vision of his future as a litigator and trial lawyer. His second big break came in the form of a job offer from the Justice Department, where he served as a trial attorney and then a supervisory assistant US attorney. He says he was “the guy who would try any case just for the experience. ‘Here’s one we’re probably not going to win; give it to Matt.’” He obtained convictions in all of them.

He later received the DOJ’s Special Achievement Award while working under Janet Reno on a federal campaign finance task force and served as an associate independent counsel in the investigation of Bill Clinton’s former housing secretary, Henry Cisneros, who admitted lying to the FBI. Rosengart honed his skills in those cases, cross examining former Chief of Staff Leon Panetta, Secretary of State Warren Christopher, and several US senators. But his proudest moment at the DOJ, he says, came when he refused to file an enhancement that would send a young Black man convicted of selling ten grams of crack cocaine to prison for life under the “three strikes” law. “My supervisor leaned on me and said, ‘Matt, this is the job and you have to do it.’ I said, ‘No, it’s not the job. My job is to do justice.’”

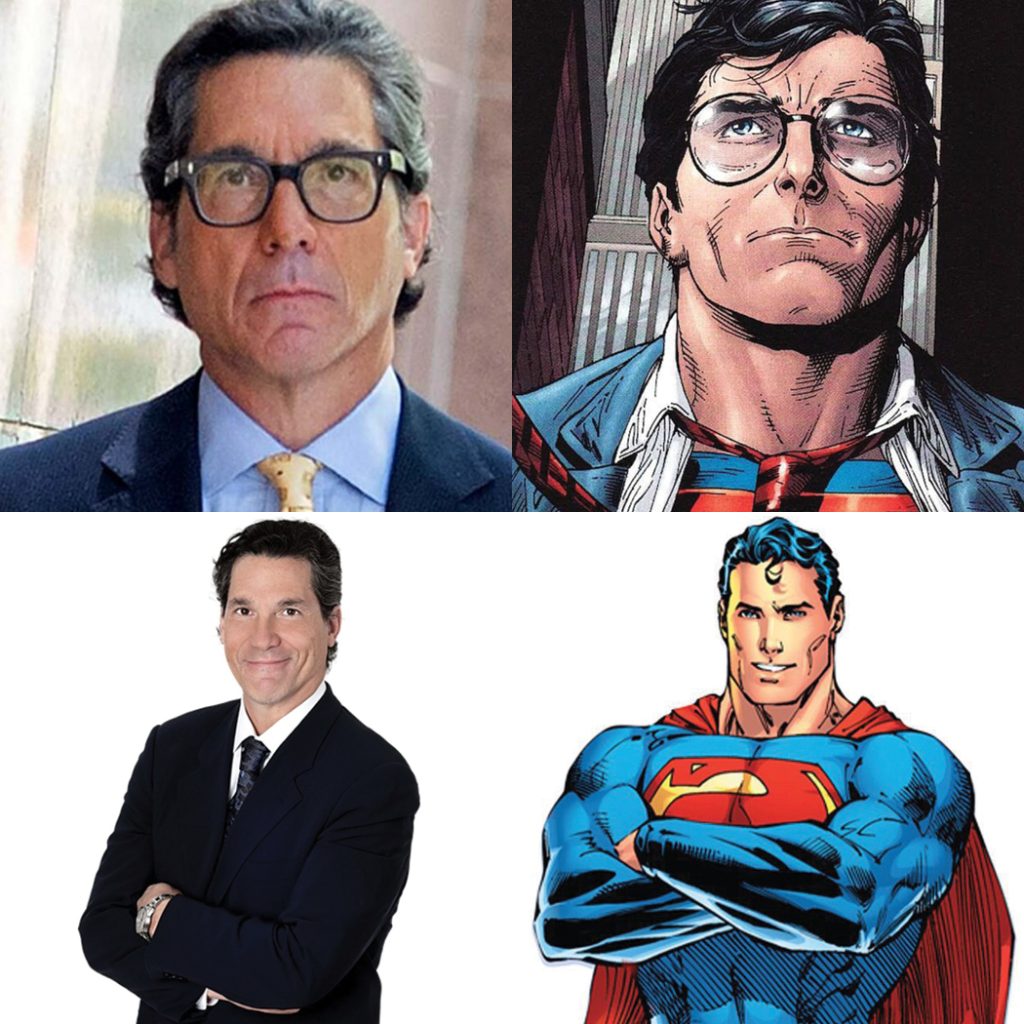

It’s that attitude that led to tweets like the one comparing pictures of Rosengart to Clark Kent and Superman below the words, “I see no difference” as he worked to liberate Spears. Like the Man of Steel, Rosengart accepts that a certain degree of renown comes with his work, but he doesn’t seek it. After a September hearing in the Spears case, he returned to his office to find about seventy-five phone calls and messages, including interview requests from several major media outlets. But, as Berliner says, “he doesn’t want to be out there on every TV show.”

“No doubt my father’s death contributed to my drive, to being in the office at midnight if I have to and making sure every comma is in the right place. Maybe I’m proving something to him or wanting him to be proud of me.”

Mathew Rosengart

Even his brother calls him “very private”—a quality that has no doubt contributed to the extraordinary degree of trust celebrities place in him. “I have utter, complete faith in Matt,” says Lonergan, who hired Rosengart when he was sued by the financier of his 2011 film Margaret and today considers him a close friend. “As much as anybody else, he’s responsible for the survival of that movie, and to some degree to my own professional and personal survival. The fact that it was resolved in my favor made a big difference to how I carried myself going forward.”

Many of Rosengart’s A-list clients—who include Steven Spielberg, Keanu Reeves, Julia Louis-Dreyfus, Pearl Jam front man Eddie Vedder, and six-time NBA All-Star Jimmy Butler—become his friends, no doubt in part because he chooses cases based not only on his level of interest in the subject matter and cause, but also on what he calls his “connection with the potential client.” He says that even the corporate cases he takes on are “emotional and personal” to him, recounting a multimillion-dollar arbitration case filed by the megarich businessman Ronald Lauder and eleven other claimants against the global financial services firm Credit Suisse, which hired Rosengart. “People think the bank has an advantage,” he says, “but I was up against billionaires and centimillionaires, and the case was crucial to me. Every case is like life and death.”

He personally cross-examined every plaintiff, wrote and argued all the pleadings and motions, and did the opening and closing arguments. “They sued for about $20 million and got zero,” he says. “But putting aside how pleased Credit Suisse was, I received notes from two witnesses in the case—people who were not famous or even well known within the company—thanking me for helping to prepare them for their testimony because if it hadn’t gone well, they would have looked bad and taken heat from their bosses.” Rosengart has won a slew of accolades over the years, including being named legal website Above the Law’s 2022 Attorney of the Year, but, he says, “sometimes the kinds of accolades in those two notes are even more meaningful to me than the official ones.”

The conventional wisdom is that for every hour in trial a lawyer spends three hours preparing, but for Rosengart it’s more like twenty. “It’s about going the extra mile for the client,” he says.

“I went to [Matt’s] LA office and he didn’t even have an assistant to carry the documents over to where the arbitration was happening. He and I carried the boxes. And this is a very fancy law firm; it’s not like he didn’t have the resources. But that tells you something about how hard he was working and how much he cared about the case.”

Director and Oscar-winner Kenneth Lonergan

“He was pretty much working for free by the end of my case,” Lonergan says. “I went to his LA office and he didn’t even have an assistant to carry the documents over to where the arbitration was happening. He and I carried the boxes. And this is a very fancy law firm; it’s not like he didn’t have the resources. But that tells you something about how hard he was working and how much he cared about the case.”

Rosengart’s longtime client Sean Penn—who, along with Justice Souter, Mary Tyler Moore, and a “handful of other celebrities,” according to Berliner, was at Rosengart’s 2006 wedding to publicist Mara Buxbaum—recently presented Rosengart with Variety magazine’s prestigious Power of Law Award. “For those of us who have had Matt in our corner,” Penn said, “we all feel that we were the only fight on his card.”

Except, of course, for truth, justice, and the American way.