Massachusetts —along with Kentucky, Pennsylvania, Virginia, and a handful of former British territories—is termed a “commonwealth,” but what is the significance of that title? On November 3, BC Law Republicans invited Mark Leduc, former minority general counsel to the Senate Homeland Security and Governmental Affairs Committee and subsequently majority chief counsel to the Senate Special Committee on Aging between 2011 and 2021, to answer that question.

Although not a historian by trade, Leduc demonstrated a passion for English history as he traced the development of the commonwealth theory of governance from its beginnings in the 17th century in response to the despotic reign of the Stuart Kings through to the modern formulation Massachusetts rests on today. After Charles I was executed in 1649 during the English Civil War, the Kingdom of England temporarily dissolved and became known as the Commonwealth of England for about a decade under the rule of Oliver Cromwell (and later, his son Richard).

As the name might suggest, the term “commonwealth” was meant to imply a new period of collective prosperity and public welfare for the British that had previously suffered under absolute monarchy. While the period was relatively short in the grand scheme of Great Britain’s history, the political theory that developed during that time lived on and greatly influenced America’s own founding generation.

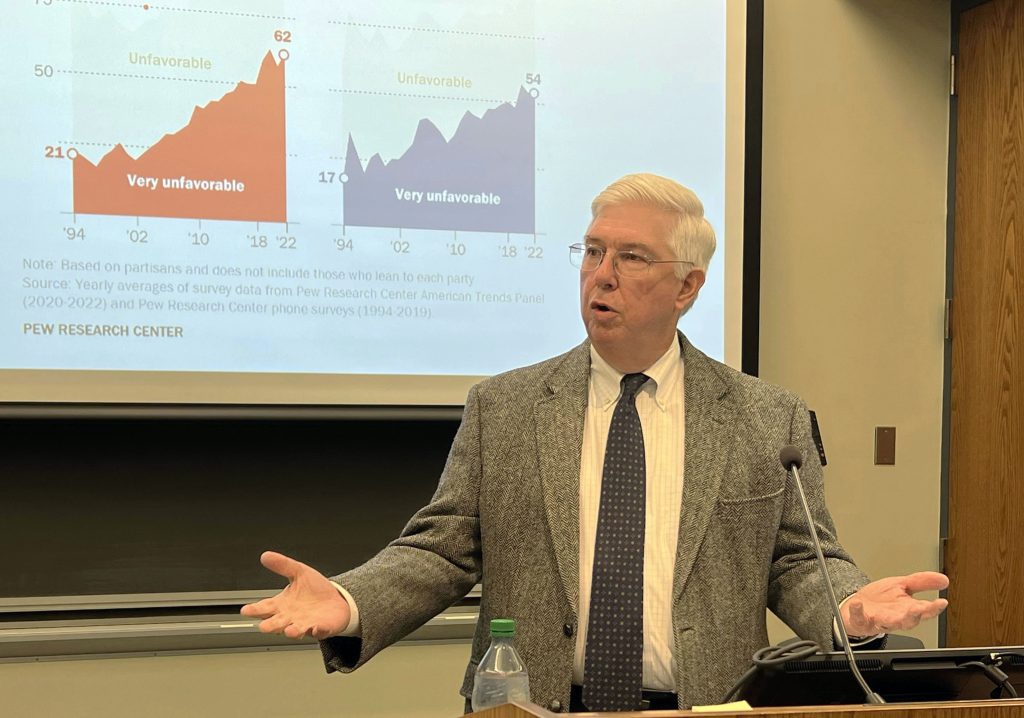

What does any of that matter today? “I want to address the elephant in the room,” Leduc said. “The United States has become increasingly polarized. You’re probably young enough to think this is the way it’s always been, but I’m old enough to know that isn’t true.” He pointed to several studies and surveys conducted by Pew Research showing that unfavorable views of Republicans and Democrats by members of the opposite party are at all-time highs, and a striking statistic showing that the vast majority of Americans (72 percent) feel that they are “losing” on political issues more often than not.

Our politics have devolved into a “lose-lose” game, as Leduc put it, far from the commonwealth ideals that once motivated politicians at the onset of our nation’s history. Commonwealth thinkers were obsessed with the idea of compromise and balance, and were starkly anti-factionalism—one can see echoes of this in George Washington’s farewell address and James Madison’s writings in the Federalist Papers. Rather than striving to find common ground, today’s politics are based on antagonism and obstruction of the opposing side at all costs, Leduc said. “I’ve actually seen, up close and personal, how that works.”

He succinctly paraphrased Madison, describing how our political institutions were created to “tie the ambition of individuals seeking their own private interests to the interests of the institution.” That is to say, the ambitions of one party or branch of government must be counteracted by the ambitions of the others as a check and balance. Supposedly, this ensures that power never accumulates in the hands of the few, and that policy remains grounded in serving the needs of the widest number of the electorate.

Perhaps a return to these concepts of commonwealth could lay the track for a future where the political parties work together to find common ground and serve the widest swath of the population, Leduc argued.