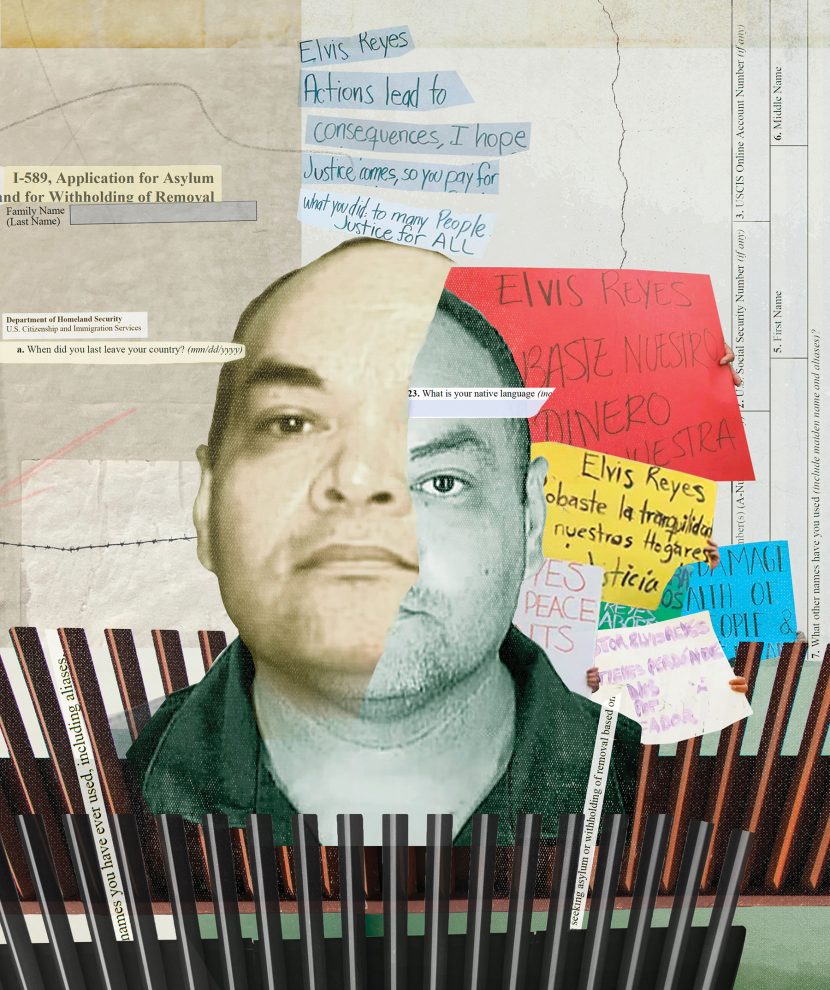

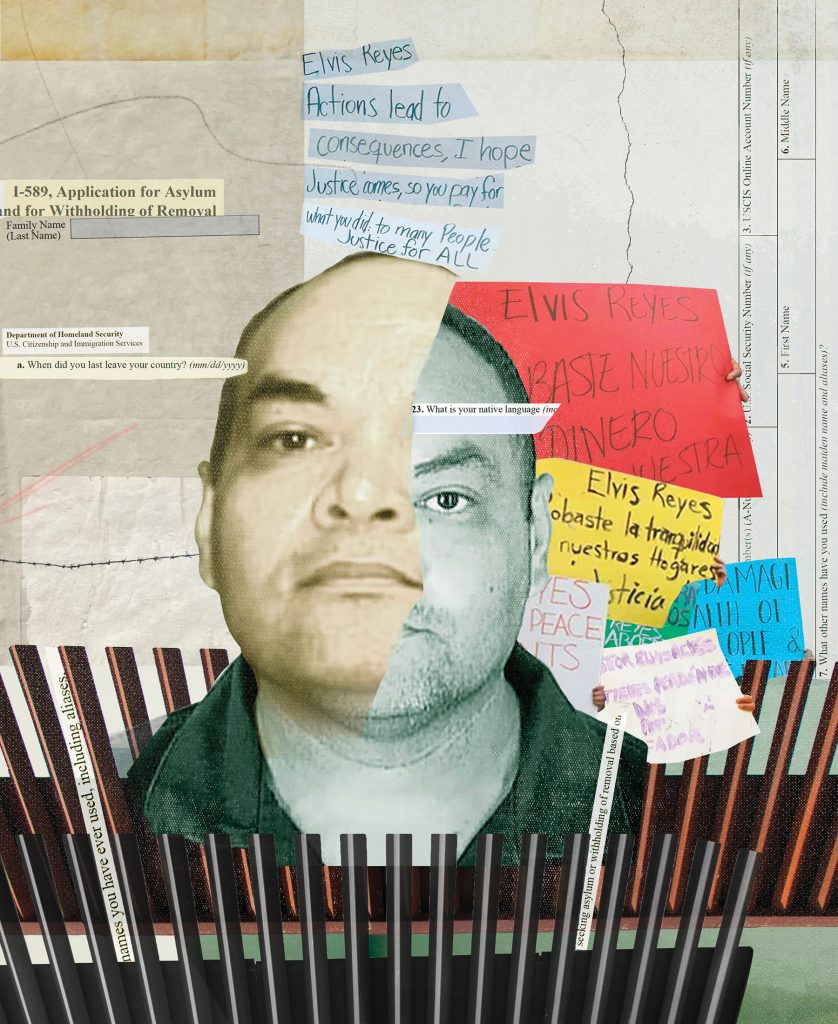

She was willing to do almost anything to live in the United States—even delay her cancer treatments. In 2018, a poor, Spanish-speaking undocumented immigrant identified in court records as “A.C.L.” paid $4,652 in legal fees to one Elvis Harold Reyes, who promised to get her a valid driver’s license and temporary work authorization. But that payment strained A.C.L.’s resources so severely that she had to postpone her life-saving cancer care. Compounding the tragedy was that the money she paid was money lost: Reyes turned out to be a fraud.

Reyes was holding himself out to A.C.L. and hundreds, possibly thousands, of others as a Christian minister and immigration attorney. He was neither. A.C.L. wasn’t the only one whom Reyes had harmed. Others were deported, or lost a path to citizenship or permanent residency, or saw their life savings evaporate. Nearly 300 individuals are known to have been his victims; there were likely more. A conservative estimate of their combined losses exceeds $411,000. Potential losses exceeded $1 million.

Reyes’s crimes were coming to light at the height of then-President Donald Trump’s scare-mongering about caravans of migrant “invaders,” and his aggressive deportation and border policies. Yet, even in less heated times, the plight of people living in America without legal status garners, at best, only limited sympathy.

Nevertheless, Frank Murray ’12 prosecuted.

An award-winning attorney for the Department of Justice in the Middle District of Florida, Murray litigated United States of America v. Elvis Harold Reyes and saw to it that Reyes was sentenced to twenty years and nine months in federal prison. But why? Why put prosecutorial resources toward crimes directed at a community that the president and a considerable swath of the American public disdained? And what does it take to coax such vulnerable people to come forward in a federal case?

Long before the Reyes matter crossed his path, Murray had ambitions to become a prosecutor. He’s still in touch with Professor Brian Quinn and with Associate Professor Paulo Barrozo, who describes Murray as possessing a rare combination of intelligence, curiosity and open-mindedness, and deep empathy for individuals and their predicaments. After graduating law school, while he was pursuing a master’s of public administration at Columbia’s School of International and Public Affairs, Murray applied for judicial clerkships and purposefully sought out Anthony Porcelli, a federal district court judge in Tampa, Florida, who had once been a prosecutor himself.

Murray rose to the top of Porcelli’s list because of a letter of recommendation from University Professor and former BC Law Dean Daniel Coquillette. “What stood out to me was that the recommendation was the highest that could be given, but it was also very personal,” Porcelli says. As Porcelli’s clerk, Murray distinguished himself through his tireless work ethic and exceptional writing skills. On Murray’s career as a prosecutor, Porcelli notes admiringly, “Frank never views his cases as wins and losses. It’s about the justice system working and presenting the evidence they’ve gathered to have a jury make that determination.”

Murray began serving as Assistant United States Attorney for the Middle District of Florida in 2015, where he led numerous investigations and prosecutions into money laundering, fraud, and corruption, and into the horrific underworld of human trafficking and child exploitation. The Reyes case came to his attention in 2018, when the investigative news team of the Spanish-language Univision Tampa Bay, Florida, first broke the story. As it turns out, both the US Citizenship and Immigration Services (USCIS) agency and the Hillsborough County (Tampa) Sheriff’s Office were already investigating Reyes. “At that point, with the media attention and us being able to play the gravitational role of bringing all these different investigatory arms together, we started looking into it from the top down,” Murray says.

Amassing the detailed evidence to build a case against Reyes required coordination among agents, police, analysts, and detectives across not only USCIS and the sheriff’s office, but also the US Department of Homeland Security and Homeland Security Investigations. “It was only a matter of time until [the case] bubbled its way up to our office,” Murray says, “but the media reporting really played a pivotal role in not only getting it onto my desk quicker, but in galvanizing community support.”

Reyes’s crimes were hair-raising. He had set up a nonprofit called EHR Ministries, Inc., through which he pretended to be a Christian pastor and immigration attorney. His advertising targeted undocumented migrants from Central America—poor people with little education and barely any English, unfamiliar with US law and bureaucracy. Reyes told them that, for a fee of around $5,000, he would file the legal paperwork necessary to get them Florida driver’s licenses and work authorizations. What his client-victims did not know was that he was filing fraudulent immigration applications in their names. He spent the money, according to Murray’s sentencing memo to the court, on “travel, luxury shopping, spas, jewelry, beautification/anti-aging procedures, and an allowance for his girlfriend.”

He got away with it for years because of backlogs in the immigration system—in particular, USCIS’s implementation of the United Nations Convention Against Torture (CAT). When immigrants file for CAT protection, they are attesting that they face the possibility of being tortured if they are returned to their home countries. A CAT filing triggers an automatic receipt letter from USCIS. That letter is the key. It enables the filer to get a driver’s license in most states, including Florida, and to get temporary work authorization if the filer’s CAT protection application is pending for a prolonged period of time (180 days).

USCIS had a long backlog of CAT protection applications, and was reviewing the oldest ones first. Knowing that no one at USCIS was going to be looking at his filings for a good, long while, Reyes just kept submitting CAT protection applications, fabricating for his unwitting “clients” unsubstantiated stories about threats and persecution and drug cartels and drug lords. He kept his client-victims in the dark by ensuring that all government mailings came to his address, not theirs.

Amassing the detailed evidence to build a case against Elvis Harold Reyes required coordination among agents, police, analysts, and detectives across not only USCIS and the sheriff’s office, but also the US Department of Homeland Security and Homeland Security Investigations.

Reyes kept one crucial piece of information from his client-victims. “What he failed to tell them was that when you file for CAT protection, you have to go to an in-person interview and explain what government-sanctioned torture you’re facing in your home country,” Murray says. “And if you don’t go to that appointment, your application automatically gets denied and you automatically end up in deportation proceedings.”

From Reyes’s perspective, it was all going swimmingly: He was raking in money, and his client-victims were getting their driver’s licenses and work papers, unaware of the legal jeopardy in which Reyes had placed them.

Things had changed in January 2018. That’s when USCIS reversed the order in which it processed CAT applications. Instead of going from oldest to newest, USCIS started looking at the newest applications first. This meant that, for the most recent applications, the 180-day “pending” period wasn’t kicking in. And that meant that Reyes’s client-victims stopped getting temporary work papers. Worse, they were getting called for USCIS in-person interviews, but they didn’t know it, and so when they didn’t appear, USCIS started referring them to immigration court for deportation proceedings.

“People started getting arrested, deported,” Murray says. “And that is when it started to unravel for him.”

Murray’s biggest challenge was going to be selecting, from a frightened and transient community, the witnesses best positioned to make the strongest case. “We went into really disadvantaged communities in Florida, mostly Spanish-speaking, first generation immigrants, who are inherently distrustful of law enforcement, especially in those years,” he says. “Having Univision consistently reporting on this helped galvanize the community. I think there’s even an article that was in Tampa Bay Times about how the victims started making friends with each other. So, there was a lot of community-building that we benefited from that we had no responsibility for creating. It just happened and it was one of the silver linings that came out of the case.” Murray continues: “I also credit my investigators, many of whom were bilingual and were fantastic at bridging that gap as well.”

Murray and his agents narrowed down the witnesses from interviews with several dozen people, after which Murray worked on putting the legal mechanisms in place to keep them in the country as the case went forward. He drafted an indictment to charge Reyes with mail fraud, visa fraud, and aggravated identity theft.

There was one dicey moment that could have triggered a loss of crucial evidence. It was when Univision television journalists confronted Reyes at his home. Spooked, Reyes asked a friend to erase his devices. The friend, however, never got around to it. “We went and talked to the friend, who gave it up. Everything,” Murray says. Investigators were even able to recover Reyes’s messages asking the friend to scrub the devices.

Homeland Security agents later went to search the premises, but by then, Reyes had moved. It didn’t matter at that point. “We had everything that we needed to present to the grand jury,” Murray says. In March of 2020, Reyes was indicted on twenty-five counts of mail fraud, visa fraud, and aggravated identity theft.

Reyes was under house arrest when Murray and his agents met Reyes and his attorney at the US Attorney’s Office to discuss a possible guilty plea. By luck of the draw, if the case were to go to trial, Reyes would be facing a Cuban-American judge sensitive to the plight of immigrants. The evidence against Reyes was overwhelming, and the witness testimony would be damning. “I said, you don’t want this judge to sit and listen to these stories for three weeks and then sentence you after you’re convicted,” Murray recalls. In December 2020, Reyes pleaded guilty to mail fraud and aggravated identity theft.

“We don’t treat people in our society, regardless of their immigration status, as falling outside the protection of law, the Constitution, or basic human rights. They’re still people and they are entitled to the same equal protection under the law.”

Frank Murray

Murray sought a sentence of nearly twenty-two years in prison. The sentencing hearing was held in April of 2021. Maybe a handful of victims, at best, was expected to show up to make impact statements in court. But something remarkable happened: Hundreds of victims came, overflowing the courtroom. There were so many that the sentencing hearing, normally a routine, maybe thirty-minute event, went on for two days straight.

“I can tell you, I’ve handled criminal cases for twenty-five years, and victims don’t always want to come to court, for various understandable reasons,” says Assistant United States Attorney Cherie Krigsman, a colleague of Murray. “I’ve been through many sentencings where victims have elected not to be physically present.” And in those cases, she emphasizes, those victims usually aren’t facing deportation and sensitive immigration issues. “This is a case that inflicted serious harm on this particular community, and those community members desired to be heard,” she says.

“It was sixteen hours of just absolute tear-jerking stories over and over and over again,” Murray says. “The things he said to these people, threats he made when they confronted him. You could hear a pin drop.”

That Murray pursued justice in this case speaks volumes about his vision of the rule of law. “Through his conduct, Reyes assumed that law enforcement would ignore his victims, that they would be voiceless, that we would ignore these folks living in the shadows of society, and that no one would pay any attention to them or believe them,” Murray says. But: “We don’t treat people in our society, regardless of their immigration status, as falling outside the protection of law, the Constitution, or basic human rights,” he says. “They’re still people and they are entitled to the same equal protection under the law.”

In the end, Reyes, at age fifty-six, was sentenced to twenty years and nine months in federal prison. Univision got an Emmy award for its reporting. And Murray received the 69th Attorney General’s Award (Fraud Prevention) from Attorney General Merrick Garland for successfully prosecuting Reyes.

And the victims? Murray says, “We tried to administratively pull levers to undo the damage to get them back to where they would have been before they met Reyes.” As for those who were deported: Murray sees no way to undo that.

After serving the Justice Department for nearly seven years, Murray is now a partner at Heise Suarez Melville, PA, in Miami, focusing on complex commercial litigation. “I do miss the work at the Department of Justice,” he says. “Nothing really replaces that: standing up and saying ‘Francis Murray for the United States.’ It’s something that was an honor to do.”