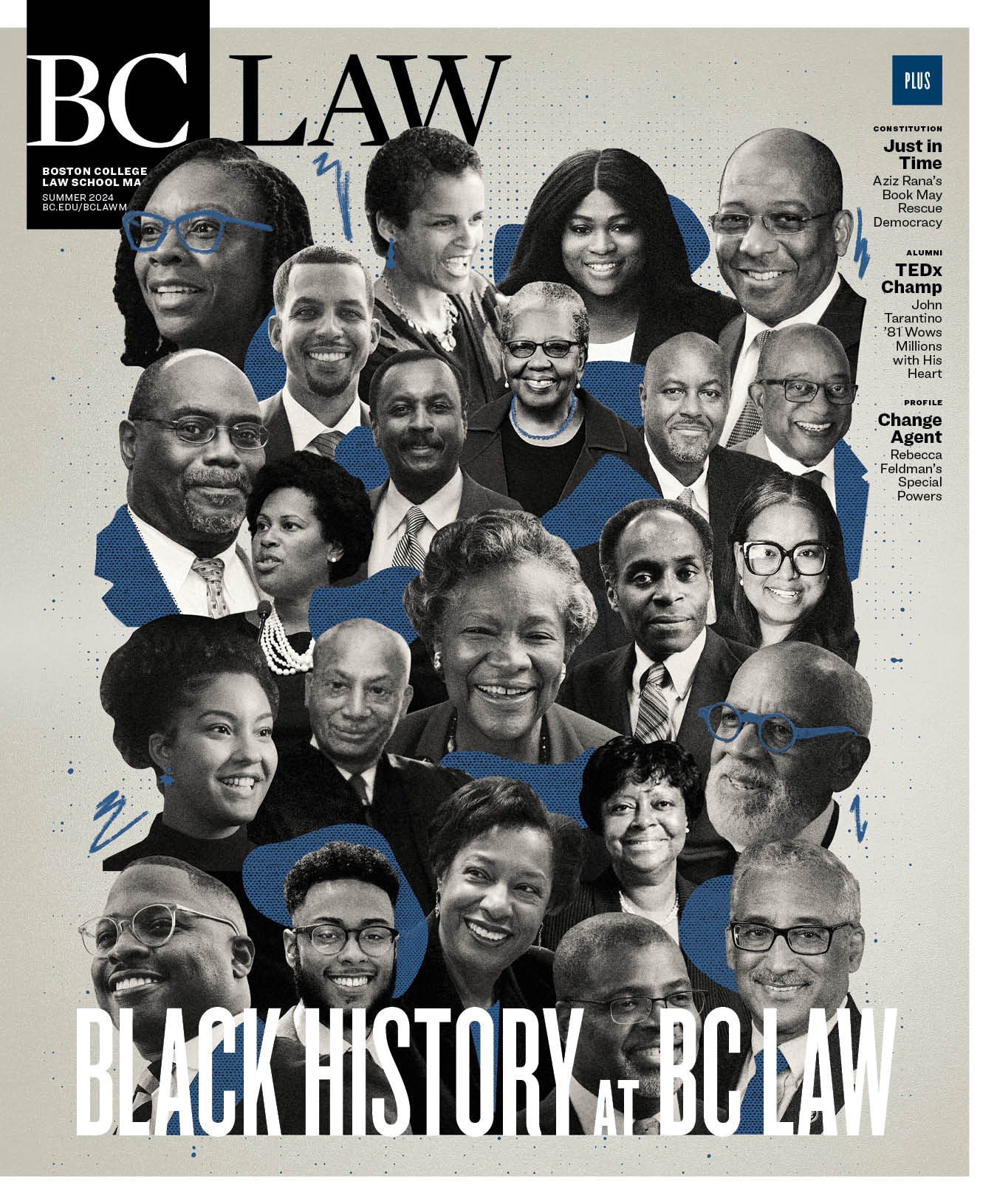

In 1898, more than three decades before BC Law’s existence, African American activist Mary Church Terrell coined the phrase “lifting as we climb.” It poetically captured the Black American ethos of rising together, an ethos that was eventually introduced to BC Law by generations of Black students, graduates, faculty, and staff, where it harmonizes with the Jesuit mission of service to others. It has guided the savvy, loving insistence with which BC Law’s Black community has encouraged the Law School to live up to its ideals, paving the way for barrier-breaking judges, scholars, law firm partners, nonprofit and industry executives, and public leaders, and changing the bench and bar forever. Much of that story is told in the form of interviews, videos, photographs, and timelines on the website “Black History at BC Law,” which was launched this past spring. Here, in the magazine, is a narrative companion to parts of that dynamic archive. It’s quite a history. Let’s take a look.

Early Years Produce Judicial Trailblazers: 1929-1969

Four African American men graduated from BC Law in the forty years after its founding in 1929. The first, Harold A. Stevens ’36, and later graduate David S. Nelson ’60, left indelible marks on the American judiciary. The other two, Thomas M. Simmons ’56 and Henry S. Quarles ’59, practiced law in Boston.

Stevens, born in South Carolina in 1907 on a farm owned by his father and formerly enslaved grandfather, followed through on his youthful ambition to become a lawyer after an African American woman and her two brothers were lynched in his town. “I was inspired to study law,” he later said, “because it was our best bet to eliminate things like this.” The segregated University of South Carolina turned him away, but BC Law admitted him, in 1933. He was elected class vice president in his third year, and went on to a successful career in labor law. His 1974 appointment to the New York Court of Appeals ended its 128-year streak of white-only judges. He died in 1990. In 1995, BC Law’s Black Alumni Network presented the Hon. Harold A. Stevens Award to Okla Jones II ’71, a US District Court Judge for the Eastern District of Louisiana.

Nelson, a Double Eagle, graduated in 1960, practiced law in Boston, and served as chief of the Massachusetts Attorney General’s Office Consumer Protection Division. In 1973, he became a state Superior Court judge. With his 1979 appointment to the United States District Court, he was the first Black federal judge in Massachusetts history. In 1992, the BC Law Alumni Association established the annual Honorable David S. Nelson Public Interest Law Award. After he passed away in 1998, Boston’s federal court founded the Nelson Fellowship, a summer program for high school students that culminates in a mock trial argued before a federal judge. Nelson was an important early influence in the building of BC Law’s Black community.

Black Recruitment Begins: 1966

Two years after Brown v. Board of Education and nearly a decade before the passage of the Civil Rights Act and the Voting Rights Act prohibiting racial discrimination and Black disenfranchisement, Father Robert F. Drinan, SJ, was appointed dean in 1956. As he sought to transform BC Law into a nationally recognized law school dedicated to social justice and reform, Drinan initiated the recruitment and admission of a group of six Black 1L students, four men and two women, to the Class of 1969.

Still, enticing aspiring Black lawyers to an essentially all-white institution proved challenging. Between 1969 and 1971, the number of Black students never exceeded three per class. One was Benjamin Jones ’69, a retired Louisiana state court judge. Another was Ruby Ann (Roy) Wharton ’69, the first Black woman to graduate from BC Law; she still runs her own law firm in Memphis.

Wharton has spoken publicly about the loneliness of being Black and female on campus in those years. Significantly, though, BC Law’s numbers would never be so low again.

A Community Flourishes: 1970-1985

Drinan resigned in 1970 to run for Congress and was succeeded by Richard “Dick” Huber, who, with Louise Clark, assistant dean of admissions, worked closely with Black students and alumni to make the law school a supportive, welcoming place for its underrepresented students. During his tenure, annual Black class enrollment often reached double-digits, achieving a high of eighteen in 1980.

Fatefully, in 1970, the community-minded Ruth-Arlene W. Howe ’74 arrived on campus. Howe availed herself of a perk that, because her husband Theodore was a Boston College professor, allowed her to take university courses for free. At Dean Huber’s recommendation, Howe audited Contracts with Professor Sanford Katz (who would become a mentor, co-author, and close personal friend). She also studied legal research and writing. Soon after, Howe was invited to apply as a full-time student, was admitted in 1971, and went on to become BC Law’s first tenured Black woman professor.

She was a founding faculty advisor to the prestigious Boston College Third World Law Journal, a faculty advisor to the Black Law Student Association (BLSA), and co-founder of the Black Alumni Network (BAN). She became a center of gravity of the growing Black community, regularly opening her home to students and alums, mentoring generously, and forging connections among the various affinity groups emerging at BC Law. The framework she helped build would raise up generations of Black law students and grads, many of whom were first in their families to attend law school and thus without a proverbial “old boys’ network” to gain traction in a white-dominated profession. Not all Black students joined BLSA and BAN, of course; some of them took different paths. But the two groups filled a crucial gap.

The framework Ruth-Arlene Howe ’74 helped build would raise up generations of Black law students and grads, many of whom were first in their families to attend law school and thus without a proverbial “old boys’ network” to gain traction in a white dominated profession. The Black Law Student Association and Black Alumni Network crucially filled the gap.

The Huber years produced such notables as Robert “Bobby” Scott ’73, the first African American congressman from Virginia since 1891; Barbara Dortch-Okara ’74, the first woman and first African American chief justice for administration and management of the Trial Court of Massachusetts; Walter Prince ’74, a founding partner of the 100-lawyer firm Prince Lobel and former general counsel to the Massachusetts Bay Transit Authority; Charles “Chuck” Walker ’78, a labor and employment discrimination specialist and former chief hearings and compliance officer of the Massachusetts Division of Professional Licensure; Steven Wright ’81, general counsel and senior vice president of the Federal Reserve Bank of Boston; Wilber P. Edwards Jr. ’84, Massachusetts Southeast Housing Court judge; Evelynne Swagerty ’84, former senior counsel to the Federal Deposit Insurance Corporation; Leslie Harris ’84, retired associate justice of the Boston Juvenile Court; and Susan Maze-Rothstein ’85, executive director of Suffolk University’s Center for Restorative Justice, among others.

Maze-Rothstein’s experience is illustrative of how this community has mattered. When she applied to BC Law, a subcommittee of the admissions committee would meet weekly to hear students from BLSA and other affinity groups advocate for the admission of applicants whose files they had reviewed and thought should be admitted. Although student access to admissions files ended by the 2000s, Leslie Harris, one of the BLSA students at the time, “advocated for my file to be accepted as a diamond in the rough,” Maze-Rothstein says.

“BLSA was looking for people who would likely excel, but didn’t look like that on paper,” Maze-Rothstein explains. She was an earnest Ivy League student struggling to complete college as a single mother. She got through law school relying on daycare for her child, a bicycle for transportation, and a part-time job. “So, no, I wasn’t on law review,” she says. But her career has been stellar: She litigated for five years, administratively adjudicated for twelve, taught law school for twenty-two, and currently advances the scholarship and practice of restorative justice. “Essentially every job that I took after law school had some connection to BLSA and BAN,” Maze-Rothstein says.

A Changed Law School, a Diversifying Profession: 1986-2006

When Dean Huber stepped down in 1985, his legacy was a changed law school. BLSA was well established and vibrant. The Boston College Third World Law Journal was shining a scholarly light on important neglected topics. BAN would celebrate a decade of recruiting and mentoring Black BC Law students and alumni. (Dean Huber’s retirement had galvanized local Black alums to organize BAN and file the papers for it with the Massachusetts Secretary of State.) A record two dozen Black students joined the Class of 1996, and BAN convened a national conference on affirmative action on DC’s Capitol Hill. Members of the Black community, like Jessup International Moot Court-winning team member Florence Herard ’86 and Yolanda Williams ’94, the first woman and first Black student to serve as the American Bar Association’s Circuit Governor, were raising the Law School’s profile nationally and globally. Black voices were heard regularly in BC Law’s student newspaper. Scholarship from Black faculty was influencing legal thought and public policy.

Young Black aspiring lawyers were choosing BC Law because, as trial attorney and law firm founder Danilo Avalon ’95 has said, it “felt like home.” Boston, with its unwelcoming racial reputation, was starting to change, in no small part because of Black JDs from BC Law stepping into leadership roles in the public, private, and nonprofit sectors—people like Damon Hart ’99, Liberty Mutual’s chief legal officer and executive vice president and the co-founder of a nonprofit combatting systemic racism; Tanisha Sullivan ’02, NAACP Boston Branch president and biopharma executive; Suffolk Law Professor Renée M. Landers ’85, the first woman of color elected president of the Boston Bar Association; and Pratt Wiley ’06, president and CEO of The Partnership, Inc., the renowned agency that fosters the development and advancement of professionals and executives of color.

And the influence of Black BC Law grads from these years extends well beyond Boston: there’s prosecutor David Michael Williams ’94, supervisor of the Public Corruption and Financial Crime Unit of the Cook County State Attorney General’s office in Chicago, and Margo Anderson ’06, retail credit team leader at the US Treasury Department’s Office of the Comptroller of the Currency in New York.

In the private sector are Robert Harrison ’01, assistant general counsel for security company ADT in Boca Raton, Florida, and Jean Gabeau ’04, executive director of Evidence Based Medicine, in-house counsel for the pharmaceutical giant Novartis in New York. And in the entertainment industry is Melissa Clark ’90, founder and CEO of the marketing agency Front Row Entertainment, in El Segundo, California. And that’s just a small sampling.

In these years, the number of Black students per class was typically in the double-digits, once exceeding twenty. But in 2007, a drop-off began, with Black class enrollment sometimes falling as low as seven.

A Reset and a Future of Promise: 2007 and Beyond

The decline in Black enrollment has been attributed to various factors: the change in the national admissions landscape; the decline in Black law school applicants nationwide; the high costs of attending elite New England institutions like BC Law; and the lingering and unequally borne systemic impacts of the Great Recession, among others.

In 2011, after a nationwide search, Vincent Rougeau, from Notre Dame, became BC Law’s first African American dean. His leadership was a beacon of hope for the Black community as he led a sustained focus on Black and other minority matters, despite the era’s cultural and economic headwinds.

In 2018, Professor Emerita Howe was moved to write to faculty and staff to share her feeling that the times called for still greater emphasis. Her point was underscored when Class President Marcus Nemeth ’19, now a Ropes & Gray associate in New York, described in his graduation speech how he entered BC Law in 2016 as the only African American male in his class. Transfers and dual-degree candidates would increase the number of Black men in the Class of 2019 to three. “With our little village as support,” Nemeth said in his graduation speech, “we all leave this institution as the next generation determined to make change and leave the door wide open so those that come after us have a less arduous path.”

“We want law schools to reflect the way that society looks. We want the courtrooms, law firms, the judicial bench to reflect what the country looks like.”

Ashley Walters ’25

Galvanized, BC Law strengthened its recruiting process and drew on the resources of its Black community. The admissions office highlighted BC Law’s access to the exciting professional environment of Boston and the region, including the collaborative, supportive Black professional network. Admitted Black applicants received phone calls from BLSA and BAN members, and were invited for a BLSA-hosted “Shadow Day,” where they took campus tours and were paired with current students to experience the BC Law community in action. BAN stepped up its activities for enrolled students, hosting BBQs, being mentors, delivering care packages, and participating even more actively in significant events. Assistant Dean of Graduate Enrollment Management Shawn McShay credits the leadership of Dean Rougeau: “He was instrumental in bringing the Black Alumni Network into the fold,” McShay says.

The outcome: The incoming class in 2021 was the most diverse in BC Law’s history—thanks in part to it being the largest class in decades with 338 graduates, forty (or nearly 12 percent) of whom were Black. The previous year, with 244 graduates, the number of Black students was seventeen or about 7 percent, which was itself an uptick. In addition to helping attract a broad range of applicants, higher numbers such as these support the continued flourishing of BC Law’s Black community, and ensure that the Law School—and the legal profession it helps to educate—is enriched with, and challenged by, perspectives embedded in multiple lived experiences.

Today, not only is the student body more diverse; so is the faculty and staff. “I think it is very exciting that you now have in place the first woman dean,” says Howe, who retired in 2009 but still comes to events like the annual Ruth-Arlene W. Howe Heritage Banquet.

Indeed, over the last three years under Interim Dean Diane Ring and new Dean Odette Lienau, the number of diverse faculty has continued to grow; in 2022 alone, three Black professors were hired.

Over the last year, at the urging of BAN and the initiative of Dean Lienau, the website “Black History at BC Law” was launched to celebrate the rise of this professional community. The site captures “the ways in which Black folk have added to the fabric, vibrancy, magic, and beauty of BC Law and the fantastic and impactful things that they have done after law school,” says current BAN President Arianne Waldron ’14, attorney for the First Circuit Court of Appeals and co-owner of the District 7 Tavern in Roxbury.

Now, future leaders like BLSA president Ashley Walters ’25 are taking up the mantle. “We want law schools to reflect the way that society looks,” she says. “We want the courtrooms, law firms, the judicial bench to reflect what the country looks like.” The key, she says, is building community: “We can help each other compete because if we all make it, it’s even better than just one or two of us making it.”

When retired judge and BAN member Leslie Harris learned of Walters’ dream of landing a judicial clerkship, he gave her the contact information of three judges. “That’s what BLSA and BAN at BC are all about,” Walters says. “Lifting as you climb.”

Special thanks to the team who researched, designed, and produced the “Black History at BC Law” website; visit bc.edu/bclaw-black-history.