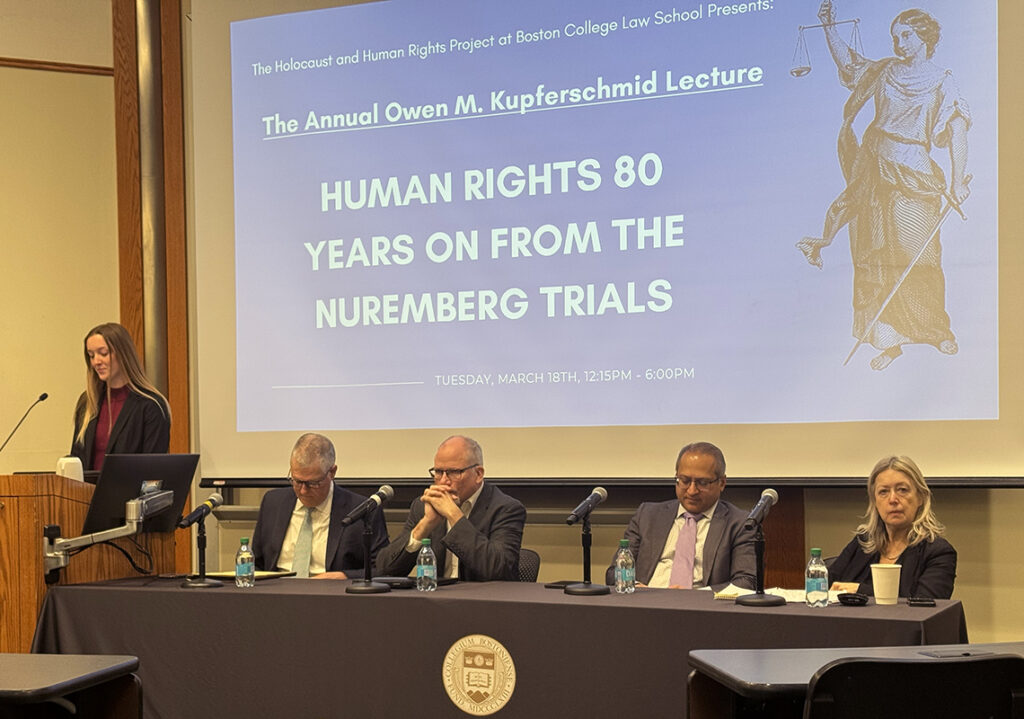

This year marks the eightieth anniversary of the Nuremberg Trials, when the allied powers formed the first international military tribunal to try a total of 199 defendants for war crimes and crimes against humanity after World War II. BC Law’s Owen M. Kupferschmid Holocaust/Human Rights Project (HHRP) commemorated the anniversary by bringing together esteemed scholars and experts for a symposium on March 18.

HHRP, named after its founder, a 1986 Boston College Law School graduate, advances awareness of human rights challenges across the globe and ensures that the historical, legal, and ethical lessons the world learned from the Holocaust are forever remembered.

After a brief introduction by Seth Kupferschmid, who paid tribute to the impactful work his brother Owen did to discuss and promote the practice of human rights law, the first panelists provided perspectives on contemporary global justice.

Ruti Teitel of New York Law School focused on a paradigm shift that occurred at the end of World War I, away from the conventional norm of collective punishment and towards individual punishment. This shift was emphasized in Nuremberg, where it was the individuals who were held responsible, a change heavily pushed by the United States. “We can see the importance of presidential leadership in resolving these conflicts,” Teitel said.

John Q. Barrett of St. John’s University Law then offered an overview of the process leading up to, during, and briefly after the trials. Early on, “war- making was a sovereign power of the states,” he explained. “The law had nothing to say about it.” That changed in 1945 when the allied powers signed the agreement to create the world’s first international criminal court, a move that demonstrated judicial independence. Today, ad hoc tribunal processes are successor institutions to Nuremberg. “Each of them is a starting point,” Barrett said. “Each of them works in extremely difficult contexts.” Additionally, these processes today are often sought in the middle of war, rather than at the end, which Barrett, explained, is a modern concept.

Devin Pendas, a history professor at Boston College, spoke about the legacy of Nuremberg, debunking popular myths about the trials, like the idea that it was the trials themselves that brought about the democratization of Germany. “The democratization of Germany is much more complicated and often has to do with the rejection of the lessons of Nuremberg, not the embrace of them,” Pendas said. “In 1946, 70 percent of Germans surveyed thought the Nuremberg trials were fair. In 1950, it had fallen to 38 percent.” Pendas explained that it was not the prosecutors, but the defense attorneys, who had the ear of the German public.

Pendas said the legacy of Nuremberg matters most because it helps articulate a culture shift around the norms of international violence that lead to a lot of self-policing. “It increasingly becomes something that is robust and real, and people look to a standard, a norm, not a law, of what is and isn’t acceptable in war time,” he explained. “That leads to political pressure more than legal pressure that can rein in the worst forms of violence, God willing.”

Aloke Chakravada, partner at Saul Ewing in Boston, talked about the trials’ impact on his own career as a prosecutor and former trial attorney at the International Criminal Tribunal for the Former Yugoslavia. There’s more to a high profile trial than just bringing an individual to justice, and for Chakravada, it was important to highlight the hypocrisy of “victor’s justice” that can occur when you impose an ex post facto judicial system on a country.

What is the purpose of a high-profile trial then? For Chakravada, the answer is twofold. “You do it to show that the system works. We’re going to honor the rights and rule of law and what our country stands for,” Chakravada explained. “Another reason is to tell the story. To make a public showing of the facts that are uncontroverted and tested in the crucible of cross examination.” He also discussed the importance of doing something to get through the trauma, to be able to understand what happened and move on.

“The Nuremberg Trials had an incredible influence on what international criminal law and humanitarian aid became,” Chakravada said. Today, he predicts that we’ll see its impact in criminal corporate responsibility, because it is often corporations that manage to escape justice. “Is corporate responsibility going to become a substitute for individual responsibility?” he asked.

Elisabeth Ryan ’06 introduced the second panel, giving a touching remembrance to her father, Allan Ryan, a BC Law adjunct faculty member for many years, and his work in international humanitarian law.

The panelists then brought a more modern take to the conversation, speaking on the laws of targeting during war and proportionality.

Mary Beth Chopas, a BC Law adjunct professor, provided a brief overview of the analysis in attacking a military objective. She explored the definition of proportionality, a complex subject that provides only vague guidance in wartime decision making. Touching on topics like collateral damage, the Lieber Code, and dual use of sites that contain both military targets and civilians, Chopas emphasized that proportionality is a difficult calculus. “Never can you overlook the protection of persons when you are furthering your military goals,” she said, adding that proportionality is determined at the moment the decision to launch an attack is made, not in hindsight.

Philip Weiner ’80, who has worked as a prosecutor and as a judge at The Hague, in Sarajevo, and Phnom Penh, added to this complexity the issue of modern technology, and how it is changing not just the battlefield but the courtroom. When it comes to shelling and bombing, the first issue is factual. Who fired the projectile that caused the damage? Weiner likened this to a murder trial, or a whodunnit. “Proving this seems easy, but believe me, it isn’t,” he said. “And you have to prove it beyond a reasonable doubt.”

Today, new forms of evidence are emerging brought about by modern technology, including drones, satellite reconnaissance photographs, interception of enemy conversation, and open source information. “Is this evidence admissible at trial? How do you authenticate each of these types of evidence?” Weiner asked. “There are so many issues in international humanitarian law that have to be determined. It is our duty to continue their efforts and try to resolve these issues.”

The session concluded with panelist Tim McLaughlin ’09, a former Marine who served during the Iraq war and later worked in Sarajevo as a prosecution intern at the Court of Bosnia and Herzegovina in its war crimes section. “I can give you my experiences with getting it right and getting it wrong in the context of proportionality,” McLaughlin said, and recounted several specific moments where he faced snap decisions that demonstrated the complexity of proportionality and what it really means to weigh civilian endangerment in the middle of an enemy attack.

“Every single person I have ever met in the US military takes the job so incredibly seriously it would blow your mind. The degree of planning that goes into killing people. The degree of planning that goes into warfare,” he said. But there’s never an easy or obvious solution when faced with the problem of proportionality. “People try to get it right, and civilians still get shot up,” McLaughlin said.

The symposium concluded with a reception where participants came together, still discussing the rules of war toward the common goal that Kupferschmid intended when he founded the Human Rights and Holocaust Project.