The prosecution of James “Whitey” Bulger in 2013 may have been the first postmodern criminal trial in which questions of guilt and innocence were drowned out by a battle over who would control the narrative. Led by J.W. Carney ’78, the defense, all but conceding that their client had committed many grievous offenses, labored mightily to buff up an image of Bulger—some would say a fantasy image of him—that the gangster himself had been polishing for years. Essentially, they argued that he might have been a crook and maybe even a killer, but he didn’t kill women and, above all, he never ratted anyone out. The government labored equally hard to show the opposite.

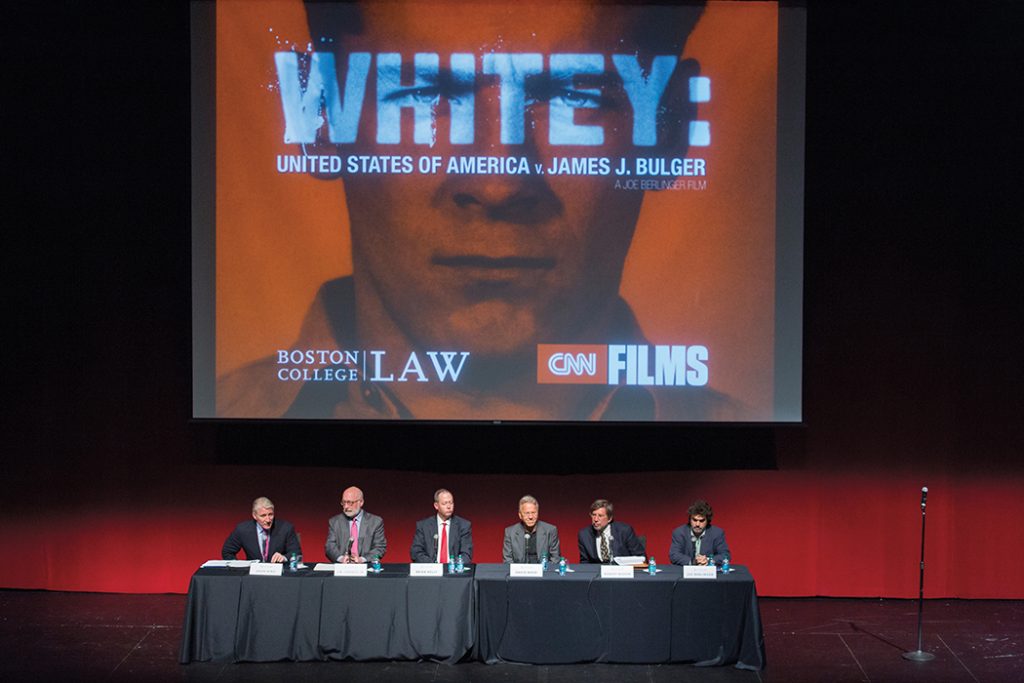

A September 16 panel about the trial co-sponsored by CNN and Boston College Law School and headlined by Carney and prosecution team member Brian Kelly, reargued the question of whether Bulger measured up to his own code of honor, and also dug into weightier matters that had gotten less scrutiny during the trial. The panel, led by CNN’s John King, immediately followed a screening of the documentary film Whitey: The United States of America vs. James J. Bulger, directed by panelist Joe Berlinger.

The panel discussion had hardly begun when Brian Kelly mentioned that Bulger had “met with about a half a dozen FBI agents over the years and gave them information.” And that, Kelly said, obviously made him an informant. Carney countered that information from his client had never “led to a prosecution,” that Bulger had never been “processed properly as an informant by the FBI,” and that he’d never been paid for information. Indeed, as Carney pointed out, it was Bulger who had paid FBI agents for information. (This included information on people who had offered to inform on him, and though Carney didn’t mention it, several of those people had ended up dead.)

While filmmaker Berlinger declared himself agnostic on the question, David Boeri, who covered the trial for WBUR radio, agreed with Kelly that Bulger was, of course, an informant; he just didn’t give very good information.

“He was not a great informant,” Kelly admitted. FBI agents like John Connolly, later convicted for his role in a few of Bulger’s crimes, had tolerated Bulger’s subpar performance as a tattletale “to advance their own careers,” explained the prosecutor, “because they could tell their superiors, ‘I have a top-echelon informant.’ It’s like being in a law firm when you have a big client.”

“What did it say about the FBI that so many agents had succumbed to the charms of a cold-blooded killer?”

As to whether Bulger really had been granted immunity from prosecution for any crime up to and including murder by the late prosecutor Jeremiah O’Sullivan—a narrative US Judge Denise Casper had prevented the defense from unscrolling at trial—Kelly said, “It’s always easy to blame the dead guy.”

Why, then, Carney wondered, would O’Sullivan have removed Bulger’s name from proposed indictments? If he’d been allowed to talk about the deal, his client, Carney said, would have taken the stand and unveiled the juicy details, presumably including how O’Sullivan believed it would benefit the justice system.

Bulger “would have been savaged under cross-examination,” retorted Boeri.

“We would have walked him through every informant report. We would have walked him through every crime,” agreed Kelly. “We would have brought up the fact that he was ratting people out since the ’50s.”

He would also have been asked to produce a copy of his agreement with O’Sullivan, a point raised by both Kelly and Boeri. Robert Bloom ’71, a BC Law professor, agreed, saying that “it’s…on the defendant” to prove the existence of an immunity agreement.

Still, Carney’s question resonated: Why had Bulger been left to kill and plunder for twenty-five years without “even so much as a traffic ticket”?

“He corrupted numerous [FBI] agents,” Kelly said. “Agents who at first began handling him as an informant became infatuated with him, he started paying them off, and that’s why [Bulger’s crime spree] went on for so long.”

This explanation was straightforward enough, but it brought up a number of other questions, some of them equally troubling. What, for instance, did it say about the FBI that so many agents had succumbed to the charms of a cold-blooded killer? Is the agency any cleaner now than back in the days when Bulger ran wild? And why was only one agent, John Connolly, ever charged with involvement in Bulger’s misdeeds? (Kelly mentioned the burden of proof and the statute of limitations as barriers to prosecution, at least at this late date.)

Another hard question came from David Boeri: Had the FBI really put heart and soul into finding Whitey Bulger during his sixteen years on the lam? Or had the bureau hoped he would be forgotten, along with its own history as his serial enabler? Boeri noted that the TV show America’s Most Wanted had reported Bulger sightings “two blocks away, three blocks away, four blocks away” from the spot in Santa Monica where he was nabbed some years later, after having been identified by a former neighbor. “I came closer to him than [the FBI] did,” said Boeri, who himself had gone to California to report on Bulger’s whereabouts. The FBI’s failure to track Bulger down “was an embarrassment for years and years,” Boeri said. “Was it simply incompetence, or was there some design?”

The question hung in the air as the panel ended.

To view the Bulger panel discussion, go to bc.edu/lawmagvideos.