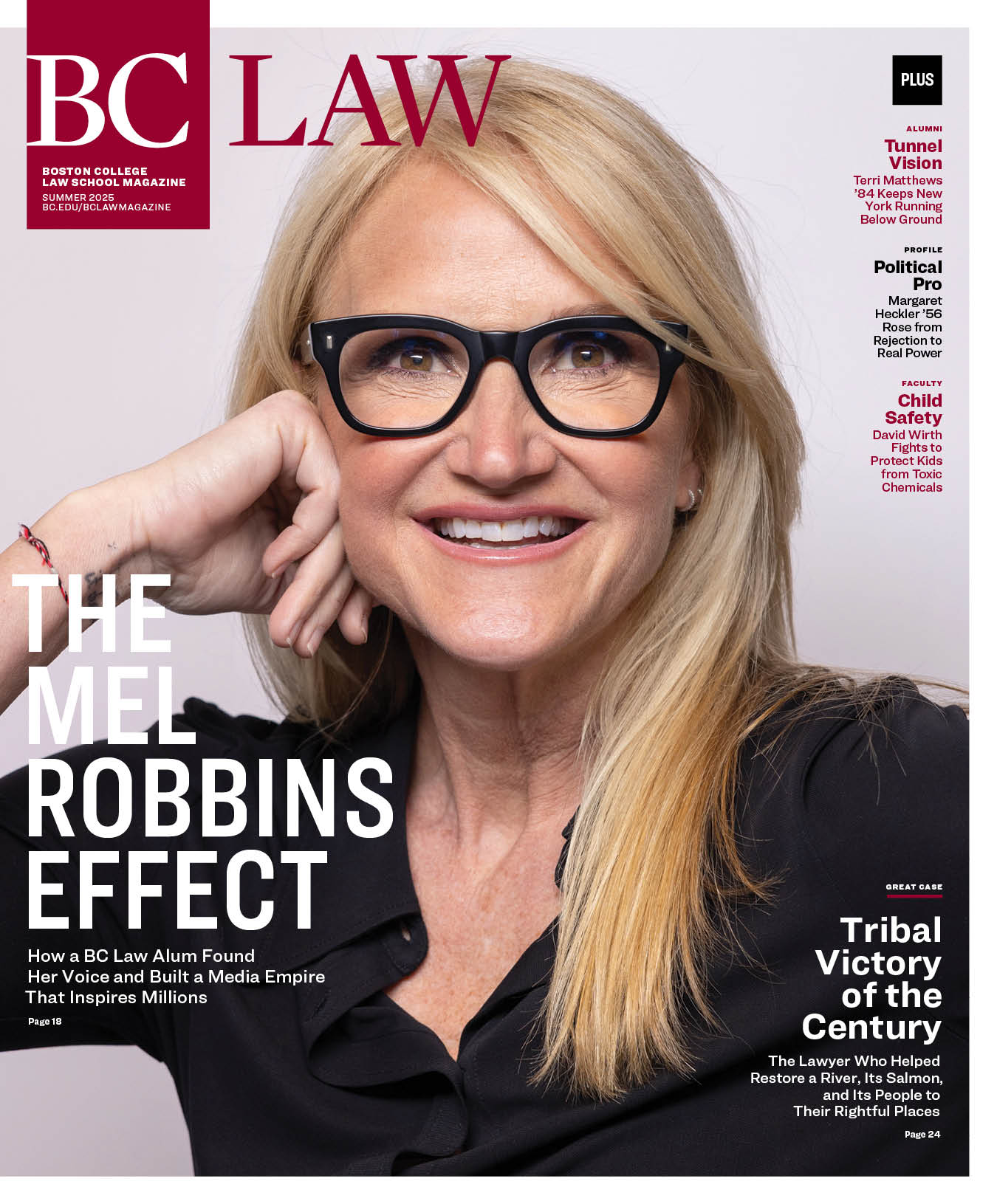

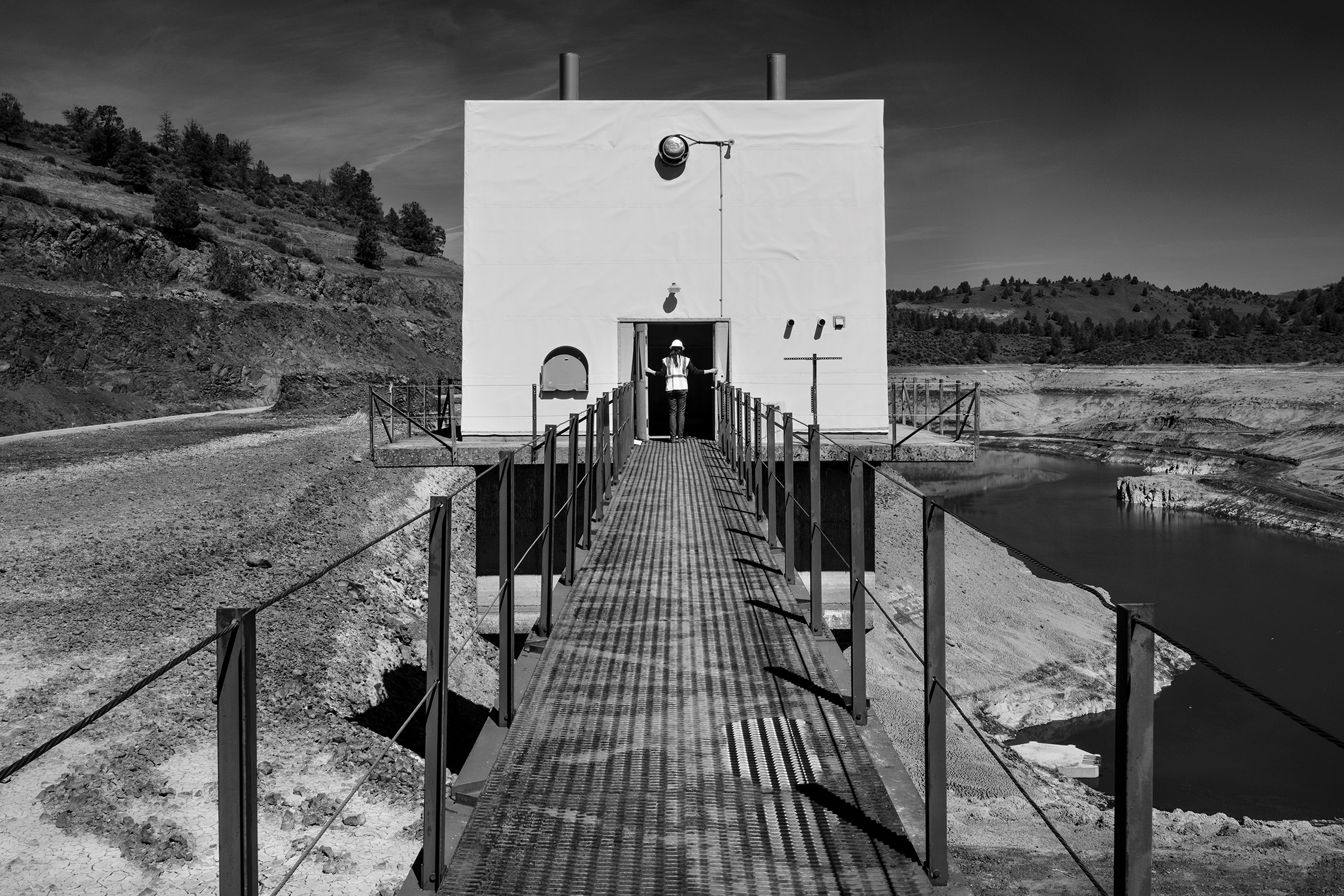

The saga of the Klamath River basin, site of the world’s largest dam removal, completed last October, is a story of withering setbacks, skin-of-the-teeth recoveries, still more setbacks, and finally, against all the odds, an unalloyed victory, the culmination of a two-decade-long campaign led by three of the basin’s four major tribes.

The basin is shaped like a wobbly Dali-esque hourglass draped across the Oregon-California border. The Klamath River was once the nation’s third most-prolific salmon fishery, before environmental insults committed by Americans and Europeans including beaver trapping, mining, logging, and lake-and-wetlands-draining to create farmland turned the waterway into a sad, denatured hydraulic machine.

The four now-dismantled hydroelectric dams, built between 1918 and 1962, were the crowning blows, walls that definitively blocked salmon from upstream spawning grounds. The dams rejiggered the river’s flows to respond to changes in electricity demand, not natural rhythms, and changed water temperatures and chemistry in ways that weren’t hospitable to river and riverine animals and plants, starting with fish. For most of this century, the basin has been considered the nation’s most embittered watershed, yet it miraculously managed to carry out a dam removal project that ranked the highest in the world in the number of destroyed dams (four), their cumulative height (400 feet), and the miles of regained river habitat (420) in which salmon may once again spawn, die, and leave behind fertilized eggs that become the next generation of salmon.

The dams’ demolition marks the end of attempts to vanquish the river by overpowering it, by using technology to generate more and more economic productivity at the expense of everything else. For the first time on the river, technology was subtracted instead of being added on, and nature was respected instead of being overrun. It’s a reminder that the social and environmental costs of dams are often far greater than the value of the electricity and irrigated water they provide, and that perseverance is vital in achieving environmental triumphs.

AS A PRINCIPAL LAWYER FOR MORE than three decades for the Yurok, the biggest and most influential of the basin’s tribes, Scott Williams ’74 was a witness and invaluable participant in the events that led to dam removal. He has taken part in the delicate, sometimes awkward dance that is often a feature of interactions between Native Americans and sympathetic non-Natives. His demeanor—calm, self-effacing, thoughtful, perennially respectful—seems to mesh with what many tribal members want from their non-tribal associates. Native distrust of non-tribal lawyers is pervasive, the residue of lawyers’ past egregious exploitation of Native clients, and potently mixes with the more general indigenous distrust of non-Native Americans for centuries of deceit, exploitation, and mass murder.

In the face of this, Curtis Berkey, Williams’ law partner and co-founder of Berkey Williams LLP, says he and Williams try to epitomize respectful behavior in their dealings with tribal members. “You have to really listen,” he said. “You have to walk a line between that and letting them know that you know what you’re talking about, that you have experience or knowledge in this non-Indian world of litigation and federal Indian law—without coming across as arrogant or knowing-it-all or patronizing.”

Williams himself describes his approach this way: “I am not Indian, certainly not a tribal member. I do not speak for my clients unless I’m standing next to them and they tell me to speak. My clients can speak for themselves. They can do it more eloquently, and they can do it their way. So, if there are photographs of signing ceremonies and things like that in [tribal] records, I’m not in ‘em. When the photographer comes, I go off to the side and I push my clients up onto the stage. And if someone asks me to speak, the first thing I say is, ‘Have you talked to the tribe? Is there anyone here you’d like to speak to?’ It is an intentional effort to avoid being the focus. There are lawyers in this world that think it’s a good idea to be the focus. I think it’s a bad idea for me given who I represent.”

Williams’ and Berkey’s expertise in Indian law is particularly useful because the field is voluminous, with a dozen or so subspecialties. The field is so immense that one of the US legal code’s 54 titles, Title 25, is devoted to it—a distinction allotted to no other social grouping. The vastness of Indian law is a testament to the length and bitterness of indigenous-vs.-Euro-American interactions, which predated the Republic by more than two and a half centuries.

Mike Belchik, the Yurok tribe’s senior water policy analyst, describes Williams as “a consummate diplomat, gracious, a good communicator.” Negotiations that Yurok leaders carried out over the fate of the dams and the allocation of Klamath River water were always “a roller coaster ride,” Belchik said. “There were times when you think, ‘We’re making progress—this is great,’ and there were times when you’re like, ‘Oh my God, we’re up against a rock wall here.’ And Scott was rock-steady, always. Every time I was freaking out a little bit, he would say, ‘We’re going to find a way through this.’ And then he would.”

AS A STUDENT, WILLIAMS SHINED. After growing up in a succession of Northern and Southern California suburbs, he matriculated at Stanford before attending Boston College Law School. Robert Condlin, then his BC Law professor and later his friend, said of him in a recent email, “He is one of the half-dozen students I remember best in over fifty years of law school teaching in five different schools.” In an ensuing phone conversation, Condlin explained that what stood out about Williams, in addition to his intelligence, was his even-handed, unflappable, amiable manner. “He didn’t make mistakes in argument, but he was also quite personable,” Condlin said. “He’s friendly. He doesn’t turn it into a contest.” And yet, for all of Williams’ graciousness, perhaps most noteworthy was this observation about Williams’ integrity: “The way he behaves has never compromised his substantive positions.”

Those views were largely formed by the time Williams left law school. At Stanford, he participated in anti-Vietnam War protests. At BC Law, one of the things he most appreciated was the existence of a clinical program that enabled him to spend twenty hours a week working for Boston’s legal assistance program while attending classes half-time. “I had a client, a young woman my age,” he said in a Zoom interview. “She had two children under ten. She wasn’t married. There was no man in her life. I remember thinking that she was really smart, had a lot of courage, was a fighter for her kids. My feeling was, that could have been my life. I knew I had a future that she didn’t have. I had the possibility of living an interesting life and she was going to work hard all her life. And that just didn’t feel right to me. What happens in your life shouldn’t turn on something as ridiculous as where you’re born and what your parents were doing. I never forgot her.”

“There are no laws in the United States that protect the cultural resources of the Yurok. There’s no law that says that the salmon, which are intimately and forever connected to every individual Yurok person, need to be protected because they’re culturally significant.”

Scott Williams ’74

Condlin’s course in negotiations, whose existence surprised Williams—“I didn’t think negotiations would be a part of a law school education”—also stayed with Williams. It introduced him to the idea that negotiated settlements among all the parties to a dispute were generally preferable to the rigid outcomes of litigation—something that his legal work with tribes would confirm. That assumption is now at the core of the flourishing Alternative Dispute Resolution movement, which supports a range of techniques from lawyer-supported mediation to plain unassisted negotiation that promise more fruitful outcomes than lawsuits.

Influenced by his experiences fighting for the rights of Yurok to fish their ancestral fishing grounds in a river with enough water in it for salmon to thrive, Williams now emphasizes the inadequate role that legal decisions play in resolving disputes. “There are no laws in the United States that protect the cultural resources of the Yurok. There’s no law that says that the salmon, which are intimately and forever connected to every individual Yurok person, need to be protected because they’re culturally significant. There’s an Endangered Species Act which says we shouldn’t let them go extinct, but there’s a difference between near-extinction and having a sustainable fishery. There’s no law we can point to and say, ‘You violated this law because you built these dams’ or ‘You ran an irrigation project badly.’ So, we have to find other ways to solve problems. This is something I learned on the job, but I was given the introductory basic principles at BC Law.”

After representing the Yurok for a decade while working for an Indian-focused law firm, in 2003 Williams and Berkey broke off to form their own boutique firm, at first headquartered in Berkeley, now in Davis, California. From the beginning, it has stood out for its single-minded commitment to representing Indian tribes—and for its frequent successes. Every one of Berkey Williams’ clients is a tribe: the firm takes on no individual tribal members, no one suing tribes or doing business with them, certainly no corporations. Williams hoped he’d never have to represent one tribe against another, but occasionally his ties to the Yurok required him to represent them in a dispute with another tribe. In 2016, for example, he filed a suit on behalf of the Yurok against a tiny band known as the Resighini Rancheria, whose members were fishing the Klamath River inside Yurok territorial waters without a Yurok permit or a California license, at a time when river conditions for salmon were dire. That case is still pending.

Four of the firm’s ten lawyers are Native American. When Williams and Berkey retire, they expect indigenous lawyers to take over the firm’s leadership. Berkey Williams eschews cases involving gaming and economic development, the two subspecialties of Indian law that attract big law firms because they involve large sums of money and the promise of juicy legal fees. The subjects that Berkey Williams takes up—Native fishing and water rights, fish management, recovery of Native land, dam removal, river restoration, health care—are immensely important but not at all lucrative. “We approach our clients by saying, ‘Let’s figure out how to solve the problem, and then secondly, figure out how to pay for it,’” Williams said. “That’s not the normal approach.” While Williams counsels his clients, he searches through nonprofits, foundations, and government agencies for funders who can cover the tribe’s expenses. Sometimes his work ends up being pro bono. Young lawyers at Berkey Williams say they’ve enthusiastically traded the mountains of cash they might have made at bigger firms for the satisfaction of believing that they are on the right side, that they are addressing injustice, that their work has lasting value.

ALONG THE WAY, WILLIAMS AND BERKEY have changed the practice of Indian law in big and small ways. In 1993, when the Yurok tribe for the first time formed a sovereign government and Williams began working for the tribe, he assisted the tribal leadership in implementing a newly drafted constitution that differed sharply from the template provided for tribes by the US government. Instead, while still conventional enough to earn acceptance by the Bureau of Indian Affairs, the new constitution reflected Yurok values and beliefs. It certainly doesn’t sound like James Madison or Thomas Jefferson. Its preamble begins: “Our people have always lived on this sacred and wondrous land along the Pacific Coast and inland on the Klamath River, since the Spirit People, Wo-ge’, made things ready for us and the Creator, Ko-won-no-ekc-on Ne-ka-nup-ceo, placed us here.”

One of the Yurok Tribe’s first victories, decided in 1995, was in Parravano v. Babbitt and Masten, a dispute between commercial ocean fishers on one side and the Yurok and the neighboring Hoopa tribe on the other. An appellate court decision affirmed the tribes’ right to an annual take of salmon, and ended up establishing the principle that regulations might be lawful and necessary outside a reservation to protect on-reservation resources. This meant that the Yurok had a right to expect regulations limiting Klamath River and Pacific Ocean salmon-fishing to protect the Yurok reservation’s salmon take.

Williams says he draws particular satisfaction from a case involving the tiny Kashia band of Pomo Indians, 680-strong, in Sonoma County, California, whose ancestors were ejected from their picturesque coastal land in the 1860s and relegated to a tiny inland ridge that faced away from the ocean—the tribe’s leader told Williams that the Kashia were “a coastal people without access to the coast.” Seaside tribes up and down the Pacific faced similar expulsions. When a rancher offered to sell the Kashia 600 seaside acres of their former territory for more than $6 million, the idea at first sounded exciting but unattainable, as the tribe lacked the money.

Williams overcame that obstacle by devising two easements for the property: he sold a conservation easement to a Sonoma County agency that was working to preserve open space and a trail easement to the state of California, which was building a trail to run the length of the state’s coast. The easements were easy for the Kashia tribe to accept because they called for treating the recovered land with respect, just as the tribe intended to do. Together with grants from two foundations, the easements covered the cost of buying back the land. “Finding that much money was not something I learned in law school,” Williams said.

Perhaps most notably, Williams helped guide the Yurok tribe as it crusaded for dam removal, from the beginning of the campaign in the early 2000s, when the idea was often greeted with derisive laughter, up to its remarkable near-success in 2010 followed by several near-fatal setbacks on the way to final victory in 2024, when the last three of the four dams were dismantled. The four dams were all owned by PacifiCorp, a Pacific Northwest utility. The coincidence that the dams came up for relicensing by the Federal Energy Regulatory Commission (FERC) in 2005, just as dam opponents were mobilizing, provided a crucial opening for the Klamath basin’s four major tribes, which initially mounted a united campaign against the dams. (The Hoopa dropped out in 2008, in a move that seemed to owe as much to tribal rivalry as to the novel legal strategy for dam removal that the Hoopa embraced to justify their act.)

“I am not Indian, certainly not a tribal member. I do not speak for my clients unless I’m standing next to them and they tell me to speak. My clients can speak for themselves. They can do it more eloquently, and they can do it their way.”

Scott Williams ’74

The 1920 Federal Power Act established the hydropower dam relicensing process, but it wasn’t until Congress passed amendments to the law in the 1986 Electric Consumers Protection Act that FERC was required to consider hydro dams’ environmental and social impacts as criteria in relicensing. Williams believes he and counsel for the conservation organizations were the first lawyers to go to trial to take advantage of those provisions in a relicensing procedure. In a trial before an administrative judge, Williams argued that PacifiCorp should be required to redress the enormous harm the dams caused Klamath River salmon, cutting off spawning grounds and altering water conditions to such an extent that the basin’s seven salmon species were all either extinct or headed that way.

The only solution, Williams argued, was the installation of fish ladders on all four dams as a condition of relicensing. It wasn’t that the tribes really advocated fish ladders—ladders for salmon had a spotty record, and did nothing to ameliorate the other detrimental environmental impacts of dams. But fish ladders would cost at least $350 million, as much as $150 million more than removing the dams, according to estimates at the time—a finding requiring fish ladders would therefore make dam removal more desirable because of its lower cost.

In effect, the tribes and their allies were in the bizarre position of having to prove that fish ladders, which they didn’t want, would work—to show, that is, that Upper Klamath basin habitat, for all its many human-induced depredations, could still support salmon—in order to make the case that dam removal would work, too. PacifiCorp maintained that fish ladders (and, by extension, dam removal) would be useless, as the river’s salmon habitat was so thoroughly ravaged that salmon recovery upstream from the dams was impossible. Given that PacifiCorp’s predecessors had built the dams that caused much of the ravaging, that was a nervy argument, to say the least. When the judge sided with the tribes, requiring fish ladders, dam removal for the first time began to sound palatable to PacifiCorp executives, and led to the utility’s 2010 decision to scuttle the dams. Williams’ successful use of the 1986 Federal Power Act amendments was a key development on the way to dam removal; without it, the dams might still be standing.

WILLIAMS’ LONG TENURE AS A LAWYER for tribes has coincided with most tribes’—and certainly the Yuroks’—resurgence as political and social entities. But the Trump administration’s recent suspension of some funding for tribes and its laying off of federally employed scientists and bureaucrats who worked with tribes on environmental issues such as river restoration has hampered tribal programs and called into question the tribes’ continued revitalization. “The threat to tribes is very real now,” Williams said. “The intention of the White House is to create chaos and uncertainty, and they’ve been successful in doing that. That has resulted in paralysis on the part of the federal people we deal with. People we’ve worked with for decades are seriously looking at retiring—it’s just been crazy for them. The tribes will lose a ton of institutional knowledge, in addition to having their funding threatened. This is going to change the federal government for decades.”

Jacques Leslie is a Los Angeles Times contributing writer and author of Deep Water: The Epic Struggle Over Dams, Displaced People, and the Environment.