Social media, police body cams, and other technologies have increasingly exposed the troubled relationships between some police forces and the communities—particularly communities of color—they serve. The Black Lives Matter movement, born of a white policeman’s shooting of an unarmed black man in Ferguson, Missouri, in 2014, is but one example of this cultural discord and the public’s growing awareness of it.

Two months after Michael Brown was killed in Ferguson, seventeen-year-old Laquan McDonald was shot sixteen times by a policeman in Chicago, exposing another dimension of the disconnect between police and citizenry. This time, a belatedly released video of the shooting revealed that some officers who had witnessed the event had fabricated accounts of the incident; they’d essentially closed ranks around their shooter-colleague to protect him.

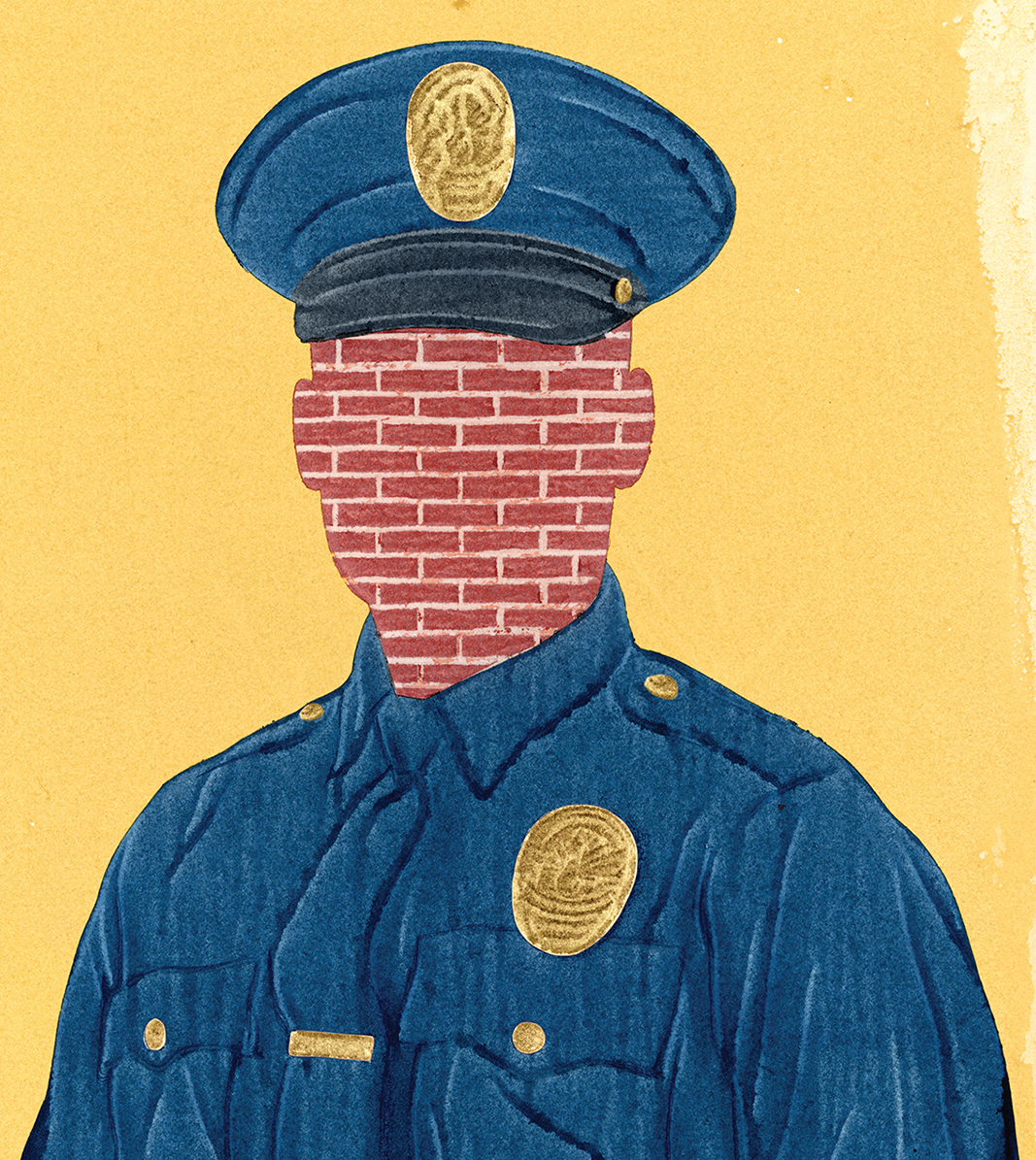

Though this so-called “blue wall of silence” does not come as a surprise, a culture of blind allegiance of individual police officers to each other is nevertheless deeply troubling and a major obstacle to reform. So, it could be argued, are police unions, which jealously shield their ranks from outside scrutiny. As much as police may believe that their culture should be preserved, neither they nor their communities will be safe without an honest coming to terms with reality.

In my years of teaching criminal procedure, I have come to understand the reasons for the wall of silence. Police are somewhat isolated. Their social context, aside from their families, is commonly limited to fellow officers. On the job, they contend with dangerous events and need to rely on each other for their safety. The patrol officer has a lot of discretion and authority to deal with circumstances on the ground. Supervising officers have come up through the ranks and share the same experience as patrol officers. The mix of isolation, danger, and authority lends itself to an extremely closed culture. Police unions feed into this same ethos.

In search of possible solutions, I went to Trinity College Dublin to study the culture of Ireland’s national police force, the Garda, which was founded on a respectful principle expressed by its first commissioner, Michael Staines, in 1921: “We will succeed not by force of arms but on our moral authority as servants of the people.”

Since 2000, several fact-finding commissions investigating the allegation of a whistleblower found corruption in the force. With previously high public confidence waning, the legislature created three independent mechanisms to address the corruption and promote transparency within the Garda. Although progress has been made, the road ahead is long.

The Garda is the only police force in the Republic of Ireland; the United States, by contrast, has thousands of forces: state, local, county, as well as federal. The Tenth Amendment to the US Constitution leaves police function to the states, so a congressional solution is not feasible. Some small measure of federal involvement is provided by the Department of Justice, which from time to time investigates individual police departments because of civil rights violations. Among its recommendations, the DOJ has called for the creation of independent civilian review boards, a move police unions oppose.

Regardless of the differences concerning police in Ireland and America, there is a common insight that emerges: The pressure is on. Citizens are demanding greater accountability and transparency, and systems will develop to achieve that, as Ireland has proven. If police want to be players in making their communities safe—even trusting—environments in which they themselves live and work, then they must begin by earning that trust. They have everything to gain by dismantling that wall of silence, brick by stubborn brick.