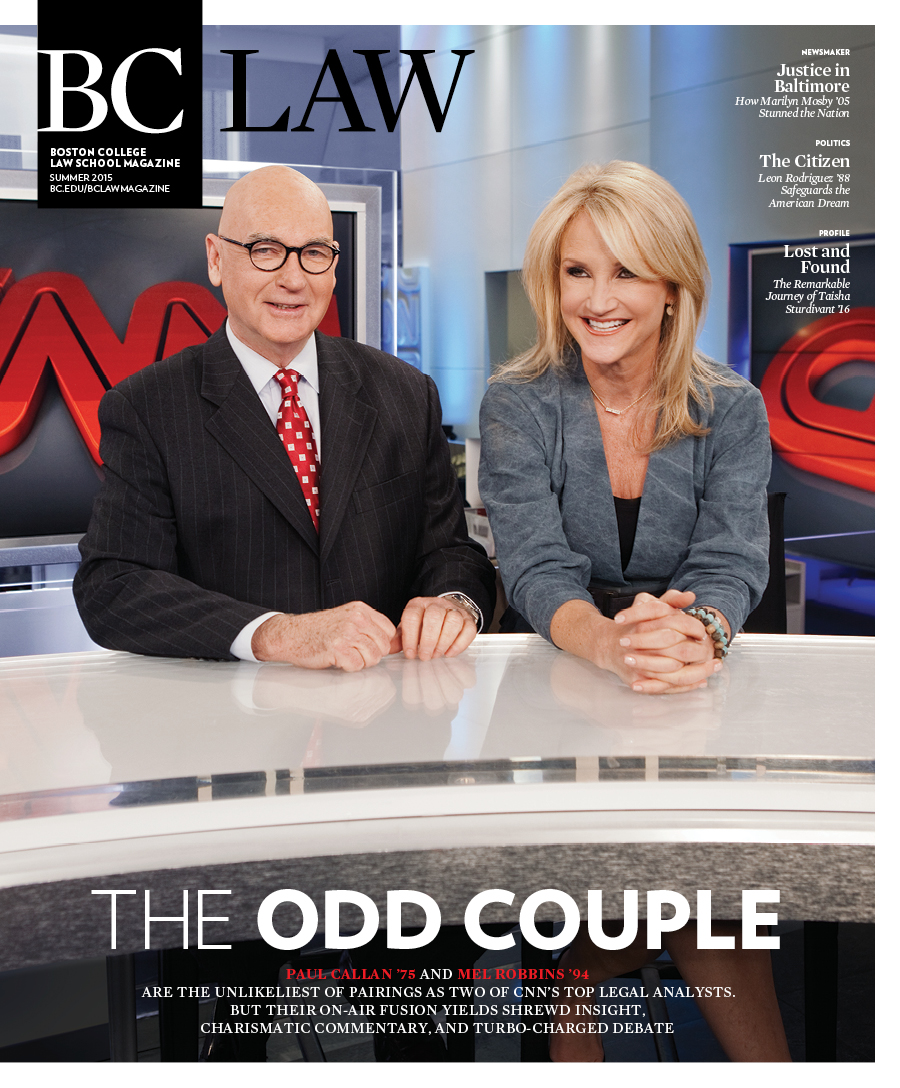

It is hard to reconcile where Paul Callan and Mel Robbins are now with where they have been. On so many levels. He drove a cab for years, couch-surfed for a spell on university campuses all across the UK and once worked six months as an ADA in Brooklyn without a paycheck. She spent her infancy living in public housing, waged war with postpartum depression as a first-time mom, and discovered her true calling at an Oprah Winfrey conference.

To be sure, cherry-picking from almost any accomplished résumé usually produces an idiosyncratic zig or zag. But as divergent as the backstories might seem from the current realities of their professional lives, the pair’s must-see-TV convergence inside the same network studio on the same shows at the same time is, at best, improbable.

Robbins grew up in a western Michigan municipality so small that CNN’s New York bureau houses nearly as many employees as her hometown has people. And in spite of an increasingly jet-set lifestyle, she still self-identifies as a “Midwestern girl,” though she defies the stereotype entirely. She is brash, brainy, and brutally honest. Titillatingly transgressive. Equal parts legal eagle and Joan Rivers with a dash of Vivien Leigh’s flair for the dramatic. That said, one gets the distinct impression Robbins would never depend upon the kindness of strangers.

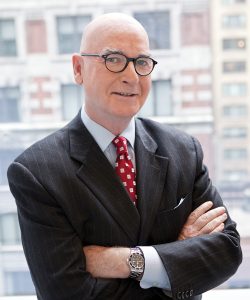

Callan is measured and methodical. He exudes gravitas and poise, possessing a ship captain’s affect, which figures since he’s a “mostly” self-taught sailor. Some CNN colleagues call him “The Professor.” Maybe. But with a gunslinger’s cool. And he is no Fred to her Ethel. Remove the politics and the marriage (though their on-air rhetoric can approximate a domestic squabble) and there’s a very real vibe of antipodal policy wonks James Carvil and Mary Matalin.

Together, these two BC Law alums comprise 40 percent of CNN’s primary stable of legal analysts. They are passionate, contentious, caring, and unvarnished. They are pals. And they remain awestruck by the privilege of the platform they’ve been afforded as well as obsessed with interpretive accuracy. Their earnest partnership—an adaptive and compelling on-screen tango—is arguably revving into cable television’s fast lane. Whatever CNN is paying them, it’s probably not enough.

“Without question, they are nothing less than a dream team,” says Ashleigh Banfield, an anchor at CNN since 2011 and now host of Legal View in CNN’s weekday noon slot. “I couldn’t be happier that they’ve agreed to sit with me on a regular basis. They are delightful and two of the smartest people on television.”

Be that as it may, birds of a feather, they are not.

Callan has been involved in some of the nation’s most noteworthy criminal and civil matters of the past four decades, serving on the prosecutorial team in the case against Son of Sam serial killer David Berkowitz, orchestrating the Nicole Brown Simpson estate’s successful civil suit against O. J. Simpson, and representing parties to past and pending actions in the Central Park 5 case. His other well-known clients as a founding partner at New York’s Callan, Koster, Brady & Brennan have included actor Leonardo DiCaprio, director Quentin Tarantino, and billionaire socialite Ivana Trump. Callan signed an exclusive contract with CNN in 2011.

“I’ve been covering trials for more than thirty years and whenever something new comes up, I’ll make a quick call to Paul and ask him about a point of law,” says longtime CNN National Correspondent Susan Candiotti. “Without fail, he can explain it for me. He’s seen different kinds of cases from all sides.”

While “The Professor” rode the express train into the legal-analyst spotlight, Robbins caught the local. She stopped practicing law almost twenty years ago after a stint with a large corporate firm in Boston preceded by three and one-half years as a public defender for violent felony criminal offenders in Manhattan. The why is quintessential Mel Robbins: “I realized that I love the law, but I don’t ever want to answer the question ‘What do you do for a living?’ with the words ‘I’m an attorney.’”

She hired a life coach, who within three weeks told her she should be a life coach. Robbins followed up by launching two self-help companies, earning a reputation as a tough-love, personal-improvement coach and a guru of CEO makeovers, then scored a syndicated call-in advice show on Sirius.

“Mel doesn’t mind doing ‘ready-fire-aim,’” says retired attorney and family friend Chris Lucas ’94, who partnered with Robbins and Ann Taylor ’94 en route to the New England championship in mock trial at BC Law. “That’s part of her charm, and I think it’s what has propelled her from a media perspective. Nothing fazes her.”

In point of fact, Robbins sports a tattoo on her right wrist that reads: It Shall Be.

Television folks began sniffing around in 2007. That landed Robbins a development contract with ABC, an on-air talent gig with FOX (on a show that never aired), and two seasons as a relationship coach on Monster in-Laws, an original reality series on A&E. The breakthrough came in 2011, when Random House published her self-help book Stop Saying You’re Fine and when her Tedx talk “How to Stop Screwing Yourself Over” became an internet sensation that now has over three million views. She made her first appearance on CNN in 2013.

Here and now, Callan’s day job revolves around his enthusiasm for civil rights advocacy on behalf of wrongfully imprisoned criminal defendants. In this capacity, he serves as of counsel to the specialty firm Edelman & Edelman, and he has the luxury of being highly selective. He has also downshifted from senior partner to of counsel at the firm he founded to accommodate the workload.

Robbins is a brand unto herself, stewarding the eponymous inspirational-speaking juggernaut, Mel Robbins: A Motivational Experience. She’s booked nearly two-dozen engagements already this year at major sales, leadership, entrepreneurship, and upper-management corporate summits. Growing this business—conceived thanks to Oprah—is her top priority.

So, what does CNN get out of all this?

“They hit at the heart of what an editorial producer looks for,” says CNN Senior Editorial Producer Marie Malzberg. “They have the depth, and they also have a little bit of Hollywood to them. They sparkle. There’s a little something extra the viewer is going to get from them. They have a good banter. There’s good chemistry. There’s energy. When they disagree, it’s a lot of fun to watch. They are such an asset to CNN, and they make us look good.”

PAUL CALLAN

First job ever: Paper boy and also a caddie at Indian Meadow Country Club in Westborough. (“A lot of the guys I carried clubs for were BC Law grads.”) Biggest risk ever taken professionally and the outcome: Quitting my job as a soon-to-be partner in a large civil law firm in NYC and hanging out my own shingle as a solo practitioner in 1980. The firm eventually grew to forty attorneys. Describe yourself in one word: Eclectic. Best piece of advice you’ve ever received: Get your fee upfront. If you could have one more hour in your day, how would you dispense that: Become more active in charitable endeavors. What is the most stressful situation you’ve handled and what was the outcome: Representing an innocent client in a murder case, because you’re always second-guessing yourself, realizing one error on your part could send a person to prison for life. Family: Wife, Eileen. Three grown children.*

Oil and Water

A typical day at CNN for Robbins and Callan is essentially a series of bench sidebars (minus the judge) cranked out at the pace of a short-order cook. And the legal landscape in 2015 has kept them busy: the Boston Marathon bombing case; the trial of former Patriots tight end Aaron Hernandez; the Ferguson, Missouri, grand jury; Indiana’s religious freedom law; the arrest of documentary film subject Robert Durst; the death of Baltimore’s Freddie Gray while in police custody; and many other hot-button legal battles. The network has been unafraid to lean on them like the two most trusted arms in a major league bullpen.

“We’re getting a lot of use and we’re both very flattered they rely on us so much to do commentary,” says Callan. “Whenever there’s been a jury verdict in a big case over the last four years, I’ve been fortunate enough to be invited on air.”

Shortly before nine on an overcast Tuesday morning this spring, they are scheduled to trade jabs at the top of the hour about the likely fate of a seventy-three-year-old reserve deputy in Oklahoma, who shot and killed a suspect while apparently under the impression he was deploying a Taser. They received this discussion topic just forty-five minutes earlier.

Callan crams in a seventh-floor holding area for on-air guests at the Time Warner Center. Robbins sits in a barber’s chair across the hall getting makeup and hair. Though both profess a high degree of solemnity for the responsibility and challenge of what they’re being asked to do each time they go live, neither exhibits any nerves. Suddenly, a frantic text from their producer kicks off a hurried dash to the fifth floor, where they need to be miked and seated at the anchor desk within three minutes.

On set, Robbins keeps things loose, bantering with bystanders and kidding with Callan, who plays along. A superstructure overhead supports a bristling array of forty production lights trained in their direction. Final show prep is executed in intense bursts. They tap on tablets. They scribble notes—she on neatly printed index cards, he in low-slung cursive on sheets of scrap paper—as the floor manager for CNN Newsroom ticks off waypoints from one minute down to ten seconds.

“It’s like a mini law school exam every single day for every single assignment,” says Robbins, who went to Dartmouth as an undergraduate. “It’s not only case law, it’s drilling down into sentencing guidelines. So much of what we talk about are stories at a state level. You have to know the facts of the case, the law, and what applies, but also the sentencing possibilities.”

The segment lasts only four minutes as the two of them serve and volley core issues of jurisprudence between prompts from anchor Carol Costello. They manage to build tension as well as explain critical and nuanced legal doctrines that will apply to any proceedings. The contrast in styles is immediately evident.

Right off the bat, Robbins reacts to a Callan comment with “What?! You really think that?!” She gawks. She mugs at the camera. It is not beyond her to turn to an anchor and declare, “I’m about to hit him” or “He’s just plain wrong.” But the stagecraft doesn’t come across as overdone. Principally because when it’s her turn to talk, she offers a point of view that’s at once plainspoken and penetrating. Robbins calls her style “ruthless compassion.” Without question, she brings a little working class frankness to her production value.

“Yeah, I can see the analogy,” says Callan. “But [she brings that along] with an Ivy League degree.”

Meanwhile, up against the vocal and vibrant handful that is Robbins, Callan trades punches artfully and with vigor. He is clear, relentlessly unperturbed, and counters her nimbly, occasionally punctuating points with a sly, all-knowing smile.

It is oil and water, and it is great television.

“Paul is the definition of what we at CNN are going for,” says Chris Cuomo, host of CNN’s New Day and the youngest son of New York’s late three-term governor. “Sure, he’s telegenic and his answers fit well into our format. But he’s got street smarts and book smarts along with the experience of being a prosecutor and a defense attorney in the criminal setting, plus he understands civil as well, so he’s a home run.”

By his own admission, some of Callan’s most pivotal preparation for a professional life that now includes jawing on CNN’s airwaves came long before he earned his JD.

He offers up his tutelage at Town Taxi and his UK odyssey mostly as a bit of color. The truth is, he drove a cab to help pay his BC Law tuition, and his hopscotch around British universities was by invitation as a national collegiate debate champion at Seton Hall. Yet both experiences strongly informed his current skillset. The former taught him much “about relating to potential jurors,” while the latter built a foundation for breakneck prep, fluid improvisation, and deft deconstruction of opposing views.

“It takes a lot of practice to develop those skills,” says Callan. “For me, it all goes back to debate. I spent pretty much every weekend of my high school and college career doing public speaking through debate. Trial lawyers require complementary, though very different skills. I’ve had a lot of practice at it through the years.”

BC Law classmate Dan Murphy ’75, a managing partner at New York’s Putney, Twombly, Hall and Hirson, suggests that practice has Callan flirting with perfection these days.

“He’s a tremendously talented trial lawyer, but I think he’s a great commentator,” says Murphy, also a longtime Callan friend. “You usually learn something and he always has some angle on it that no one else has seen. He doesn’t do it with histrionics. He gets his point across, but he’s not saying this is the only way to look at it. He doesn’t try to be somebody else. That doesn’t mean he’s not hard-hitting. He comes across as an earnest, sincere lawyer, and it works. And the great thing is, it’s true.”

Murphy, like Callan, arrived at the Brooklyn DA’s office in 1975 and both went uncompensated throughout the Big Apple’s worst financial crisis in history. Despite that inauspicious start, the considerable breadth of Callan’s lengthy CV serves him well when he has to go toe-to-toe with Robbins.

“I love the way he puts together his arguments,” says CNN legal analyst Joey Jackson, an attorney at Koehler and Isaacs in Manhattan. “He has a way of countering your point by getting his own point out there without demeaning the person he’s with. He’s got that air and that aura of invincibility about him. Mel is a tightrope walk, but nobody walks the tightrope better. Paul’s got a completely different style from Mel, but a very effective way about how he approaches things. It’s not hard to recognize the heights Paul and Mel have reached, and it’s because of their ability.”

Cuomo agrees that though Callan and Robbins often plug into the issues with an AC/DC flow, the meeting of their minds results in a high-voltage, cross-section in terms of the viewer experience.

“When you compare Paul to Mel, as soon as the picture goes up on the screen, the guy’s at an immediate disadvantage—after all, it is a visual medium,” quips Cuomo. “But Paul isn’t just some guy who’s well-spoken, succinct, and provocative. There’s genius that is fundamental to his daily existence for our purposes on television.

“Mel gives you all of those things we’re looking for, but also some palette of humanity,” he continues. “Because it’s not just about the facts, it’s about the feel. She gets the difference between someone having the right to do something and something being right to do. I think it’s easy to watch them and be in a state of wonder about how they are both so accurate and insightful, and they do it in a manner on TV that is not easy.”

Cuomo’s callout speaks to how seamlessly the duo juggles the law and an anchor-desk chaperone while still managing to generate entertainment value. Some of their punchiest exchanges are pure magic, and transcripts prove that anchor Banfield’s show often produces prime examples. Even when they side with one other.

This was the case after a Ringling Brothers circus accident last year in which nine acrobats suspended by their hair were injured after plunging to the ground when equipment malfunctioned.

Banfield: OK, Mel, I decide to hang from my hair thirty-feet up and spin around … don’t I assume some of the responsibility when I do death-defying stuff and then give up my right—

Robbins: The hair didn’t detach. What happened [was] an equipment failure … maybe a sprained ankle, maybe a broken wrist you’d presume might happen in this line of work, and there’s workers’ comp to take care of that. [But] if they can prove something wrong with the equipment or the way it was assembled—maybe there was a union involved [at the venue]—they might have a tort action.

Callan: Absolutely.

Banfield: [But] their job is very, very dangerous.

Robbins: But it’s not to fall from the sky because of the equipment breaking.

Callan: If [the job is] hanging from your hair, it’s still your job, so it’s workers’ comp. But if there was an equipment failure … that’s a products’ liability case … they can sue the equipment manufacturer. And you make more money in those lawsuits than you get in workers’ compensation benefits.

Robbins: I’d like to see Paul try to do that. Hang from your hair up there, Paul.

Callan: That’s very cruel of you to say.

Banfield: Best joke ever on this set.

Robbins: He can take it … he’s smarter than me, so I got to hit below the belt.

MEL ROBBINS

Favorite word: Any four-letter word. Least Favorite Word: Can’t. What turns you on creatively, spiritually, or emotionally: Helping people reach their potential. What turns you off: Mean people. The sound you love most: The sound of my kids coming up the stairs when they enter the house. What profession other than your own would you like to attempt: Best-selling author or a filmmaker. What profession would you not like to do: A corrections officer. My hat goes off to those folks. I’d hate to be with folks who are locked in a prison all day. Family: Husband, Chris. Three children, ages ten, fourteen, and sixteen.*

What’s in a Name?

Within an hour of stepping off the Newsroom set, Callan and Robbins are breakfasting in the bureau’s tenth-floor cafeteria, which boasts a panoramic view above Manhattan. Even more breathtaking than the sweep of scenery is the fact that during their brief journey between floors, the two of them greet more than a dozen fellow employees—from security guards to camera operators to cooks—by their first name. Robbins, who lives in a leafy suburb west of Boston, casually explains the mind-blowing phenomenon.

“When I was given the opportunity to join CNN, I realized I could either be that chick up in Boston that you call for legal stuff, or I could figure out a way to really feel connected to the organization,” she recalls. “So I made a decision … to learn the names of everybody in the building. From the moment you walk in on 58th Street, all the way up. One day, Paul walks in with me and sees this and decides he has to learn all the names too. Now, it’s like a competition to see who knows more names. What happened was really interesting. By taking an interest in other people, we’ve become known inside the organization. It’s the smallest things in life that make the biggest difference.”

Over eggs, Callan and Robbins talk shop. They’ve already huddled industriously with an executive producer regarding their scheduled noon appearance on CNN’s Legal View, where they will discuss jury deliberations in the Hernandez trial. Robbins is hoping a verdict will be reached so she can cancel her 3 p.m. Amtrak home and remain available for the network’s resulting round-the-clock coverage.

There is a profound efficacy to their dialogue. So much so, they have enough margin to whistle while they work.

“This job is stimulating, exhilarating, collaborative, constantly changing, and very fast-paced,” says Callan, a native of Worcester who set down permanent roots in New York after arriving in 1975.

“All of the meaty stuff happens off-set,” adds Robbins. “We’ll spend an hour or two talking about cases, sharing research back and forth, maybe making a call or two to a buddy who specializes in a certain area of law. Then we rush from makeup and hair to the set, and we’re on for just three minutes.”

Given their on-air fireworks that routinely resemble the Yankees-Red Sox animus, the words “collaborative” and “sharing” seem a tad tough to swallow.

“It’s not about us as individuals,” insists Robbins as Callan nods approvingly. “It’s about the product being incredible. Because we’re such good friends and really respect each other and understand each other’s strengths, even though I might vehemently disagree with Paul’s interpretation, I’m still interested in what he has to say. I might even steal some of it for the next segment. Because he does change my mind and I know I do the same.”

Finding balance, then, is both the art and the craft of their task.

“When you argue everything to the extreme and there’s never any concession, you lose credibility,” says Robbins. “We also understand the job. It’s not to sit there and say, ‘You’re right, Paul. Great analysis.’ The job is to tease out the nuances of the topic and argue the law so that people are both informed and entertained.”

Callan, scrolling on his phone, suddenly redirects the flow. He’s received a plea via email to accept an emergent criminal negligence case from an incident in the city the night before.

“Should I take this case, Mel?”

“Are you nuts? You’ve got a lot on your plate.”

“Mel is my career consultant,” Callan muses.

Now, it is Robbins’ turn to interrupt. A producer is texting her for their count-by-count predictions on the Hernandez verdict so an onscreen graphic can be constructed. Callan wants to warm up for this component of their discussion, but Robbins shuts it down, “Let’s not get too deep into this right now, let’s save it for the air.”

Callan leans in with a grin. “Like we wouldn’t argue on the air if we didn’t have [the counts] to talk about.”

Incongruously enough, their interpersonal ease is clearly the wellspring of their success as a feisty professional tandem. Their authenticity when cameras are rolling is little more than an extension of their affinity off screen.

Robbins’ love of pre-cue levity is as much a coping mechanism as it is a character trait. As a young lawyer, she was plagued by neck rashes caused by pre-trial anxiety. The affliction was pronounced enough for her to conceal it with a scarf or turtleneck, even in summer.

“I would get these big, blotchy neck rashes and I was so scared the jury would think that it meant I was worried my client was guilty,” she recalls. “I finally realized I might as well just call out the elephant in the room. Over time, I would stand before a jury during voir dire and say, ‘I don’t know why, but I tend to get red as I talk and my chest gets all hivey, and it doesn’t mean this dude’s guilty.’ I made a joke of it. It’s just my genetic makeup. It always got a laugh. And because I stopped focusing on the rashes, they went away.”

During the Hernandez trial segment, Callan and Robbins predict a hung jury on the two murder counts and the weapons charge (they were both off the mark). Callan tends to take such missteps harder than she, but the merit of their misguided message is most assuredly the medium. He gets from A to B with a sniper’s precision, while Robbins shoots from the hip. Interestingly, her husband predicted she’d last three months before uttering something irrevocable on live TV.

“I remember the first time I appeared on air with Paul and I was like, ‘This guy is a smooth operator,’” says CNN’s Jackson. “He’s conversant with the law, he brings the perspective of his experience and knows how [an issue] relates to things he’s done in the past. Meanwhile, Mel is absolutely not going to run away from the controversy in what she’s talking about, but she’s going to add just enough flavor of diplomacy to what she says to get her point out in a very straightforward way that’s no-nonsense, but not offensive. It’s like, ‘Damn man, how’s she’s doing this?’”

The net for Time Warner is a product that competitors might try to imitate, but will struggle to duplicate.

“I trust and depend on them inherently for their insight, their wisdom, and their research acumen,” says CNN’s Banfield. “We change topics at lightning speed, sometimes when we’re live on the air. Relying on someone’s foundation in that setting is a sticky wicket, but when Paul and Mel are on the air, we’re solid. They are bright, articulate, clever, funny and terrific broadcasters and that is a hard combo to find. There are plenty of smart lawyers out there in the sea. To find one who is engaging, magnanimous, fun, and easy to work is a very tough get.”

It appears that CNN has found two.

Chad Konecky is a regular contributor and a freelance writer based in Gloucester. He also serves as a National Director on behalf of the USA TODAY Sports Media Group.