Margaret Heckler kept a sign on her desk that read: “Whatever women do, they must do twice as well as men to be thought half as good. Luckily, this is not difficult.”

Heckler, who passed away August 6, 2018 at the age of eighty-seven, knew what it took to forge a career in elite male-dominated arenas. At BC Law, she was one of only two women in her class (and the only woman to graduate in 1956) and she was the first woman from Massachusetts to be elected to Congress without succeeding her husband.

Born in 1931 in Flushing, New York, to Irish immigrant parents, Margaret Mary O’Shaughnessy relied on her brains, drive, and staunch Catholic faith to make her way in the world. “Her motto was ‘work hard, study hard, pray hard,’ and she was never idle—she could out-study, out-last, out-perform any other human,” said her daughter-in-law Kimberly Heckler.

Heckler’s introduction to politics was to run as Speaker of the House for the Connecticut Colleges’ Student Legislature, as an undergraduate at Albertus Magnus College in New Haven, Connecticut. Her future husband John M. Heckler managed her campaign, and the pair had to ask the mother superior’s permission for Heckler to miss curfew, so that she could campaign on other college campuses. Margaret was allowed to go, under one condition: “WIN!!” she was told. She won by a large majority, the first woman to hold the office.

After graduation she and John Heckler, now married, both applied to and were accepted at Harvard Law School. The dean advised that student marriages rarely survived law school intact, so Margaret Heckler headed instead to Boston College Law School, graduating sixth in her class.

In the mid-1950s, Heckler faced discrimination when she applied to established Boston law firms. “They told her, ‘You’d only be considered as a secretary—you’ll never go further here,’” said Kimberly Heckler. So Margaret went into private practice, volunteered in Republican campaigns, and in 1958 became a member of the Republican Committee for Wellesley, Massachusetts, where she and her husband raised their three children.

Heckler defied the Republican establishment in 1966 by running in the primary against veteran Congressman Joseph W. Martin, who had represented Massachusetts’ 10th district since 1925. She won, and went on to beat her Democratic opponent in the general election. She soon built a reputation as her district’s champion in Washington, DC, setting up a toll-free hotline for constituents, making weekly visits back home, and promoting policies that benefited local interest groups.

Her son John fondly recalls his child’s-eye view of southeastern Massachusetts towns while riding in the back of an Oldsmobile convertible, and his certain belief that the petite whirlwind at the wheel—Heckler stood five-feet-one-and-a-quarter inches tall—was a super-hero “capable of leaping tall buildings and stopping locomotives.”

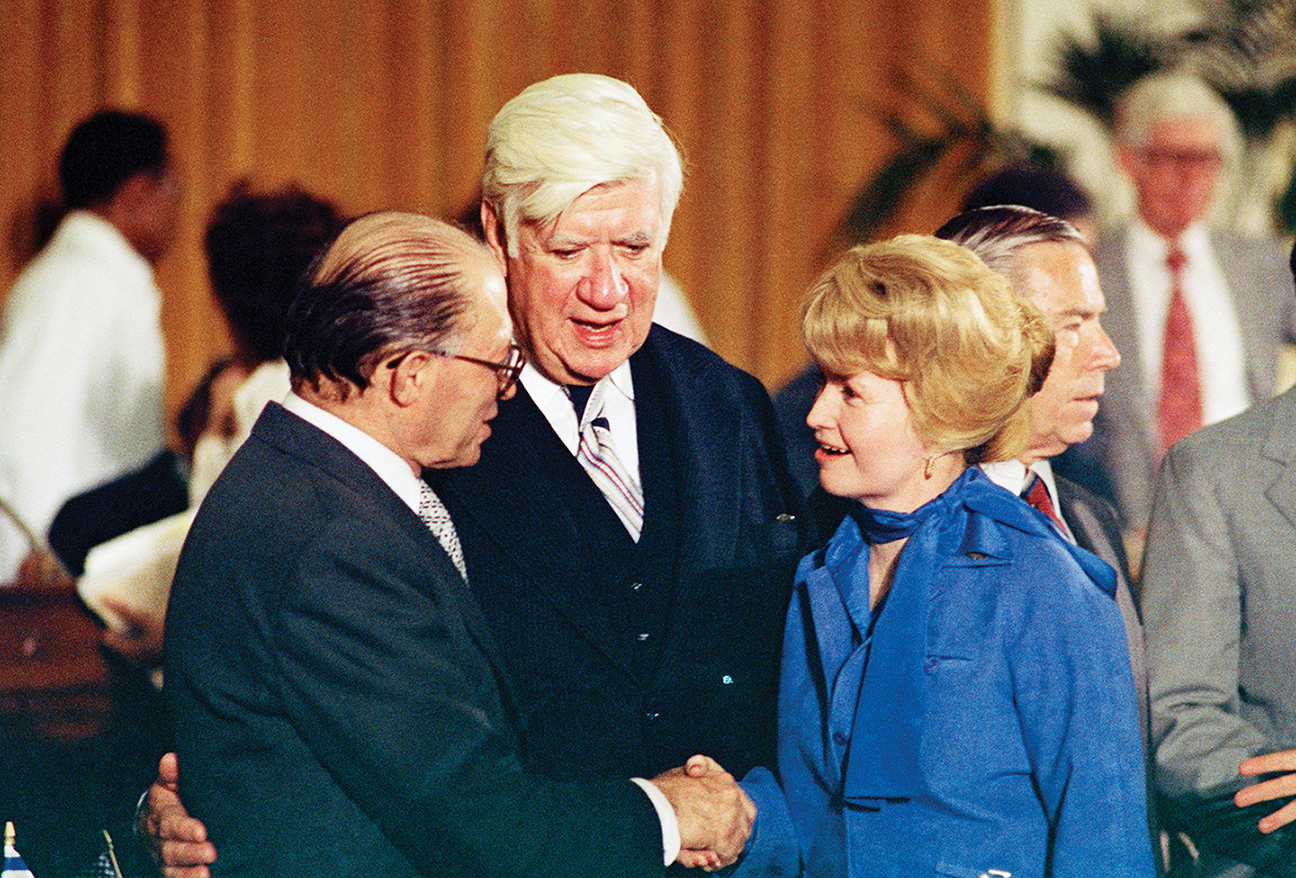

As one of only eleven women in the 1967 House of Representatives, Heckler saw an urgent need to build support for women’s causes. In 1977, she founded and was the author of the Congressional Women’s Caucus that later became the Congressional Caucus on Women’s Issues. She planned it as a bipartisan group. Heckler pushed for the Equal Rights Amendment and was the lead House sponsor of the 1974 Equal Credit Opportunity Act prohibiting discrimination in lending based on gender or marital status.

In 1982 Heckler was the most senior Republican woman representative in the House when she lost her seat to Democratic freshman Representative Barney Frank following congressional redistricting in Massachusetts. The unexpected end to Heckler’s congressional career coincided, fortuitously, with efforts by the GOP to bring more women to the fore, and in 1983, President Ronald Reagan nominated her to head Health and Human Services (HHS), a department with 145,000 employees and a $300 billion budget.

Heckler called the job the greatest challenge of her life, vowing at her confirmation hearings to be “a catalyst for caring.” At HHS, she “kept a frenetic schedule and buzzed with physical restlessness, talking fast and walking faster; aides carrying briefcases struggled in her wake as she marched ahead in high heels,” recalled her long-time speechwriter and Wellesley neighbor Beth Hinchliffe. Always a quick study, Heckler faced the public health crisis sparked by the emerging HIV/AIDS epidemic, which she called the country’s “number one health priority,” and for which she demanded increased federal funding. She also expanded funding for research into breast cancer and Alzheimer’s.

Her greatest legacy at HHS was the groundbreaking “Heckler Report,” a nine-volume study documenting disparities in health and life expectancy among minority populations that led to the creation of the HHS Office of Minority Health. Heckler’s priorities alienated conservative Republicans, who favored spending cuts to Social Security and other welfare programs. This ideological divide, coupled with adverse publicity surrounding her divorce, led to her being pressured to step down from the post in late 1985.

When Reagan offered the consolation prize of the US Embassy in Ireland, Heckler overcame some initial reluctance and tackled her new appointment with characteristic energy. According to the Washington Post, by 1987 the ambassador’s residence in Dublin’s Phoenix Park had become a salon for Irish and American politicians and cultural and business leaders, and Heckler won popularity for her efforts to promote American investment in the economically struggling country.

“Margaret was always throwing a party, wherever she was,” recalled Kimberly Heckler, who first visited the residence as the twenty-something girlfriend of the ambassador’s son. Breaking off from preparations for a party to promote Anheuser Busch, Margaret Heckler whisked her up in the elevator to the best guest room and assigned a maid to help her settle in. “I found that this woman who’d risen to such a level of power was so compassionate and kind,” said Kimberly.

“Margaret kept a frenetic schedule and buzzed with physical restlessness, talking fast and walking faster; aides carrying briefcases struggled in her wake as she marched ahead in high heels.” —Heckler speechwriter and Wellesley neighbor Beth Hinchliffe

One of his mother’s favorite sayings, her son John recalled at her memorial service, was: “I will rest when I am dead.” After her return from Ireland in October 1989, Heckler worked tirelessly for Catholic charities, received numerous honorary degrees, and served on many boards, including the National Alliance for Hispanic Health. “I became very devoted to affirming the faith for all people,” she told the New York Times. As sociable as she was devout, the day before she died she was in her element at a brunch party at the elite Cosmos Club in Washington, DC, sharp and gregarious to the end.

“She was the last of an era,” said BC Law Professor George Brown. “She is a sort of bridge to the time when we were a genuine two-party state, when there were a substantial number of Massachusetts Republicans in Congress, which makes her historically significant.”

NOTE: The John J. Burns Library at BC holds the Margaret Heckler papers and expects to make the archives available for research in fall 2019.

Heckler Portrait: Thomas S. England/The Life Images Collection/Getty Images