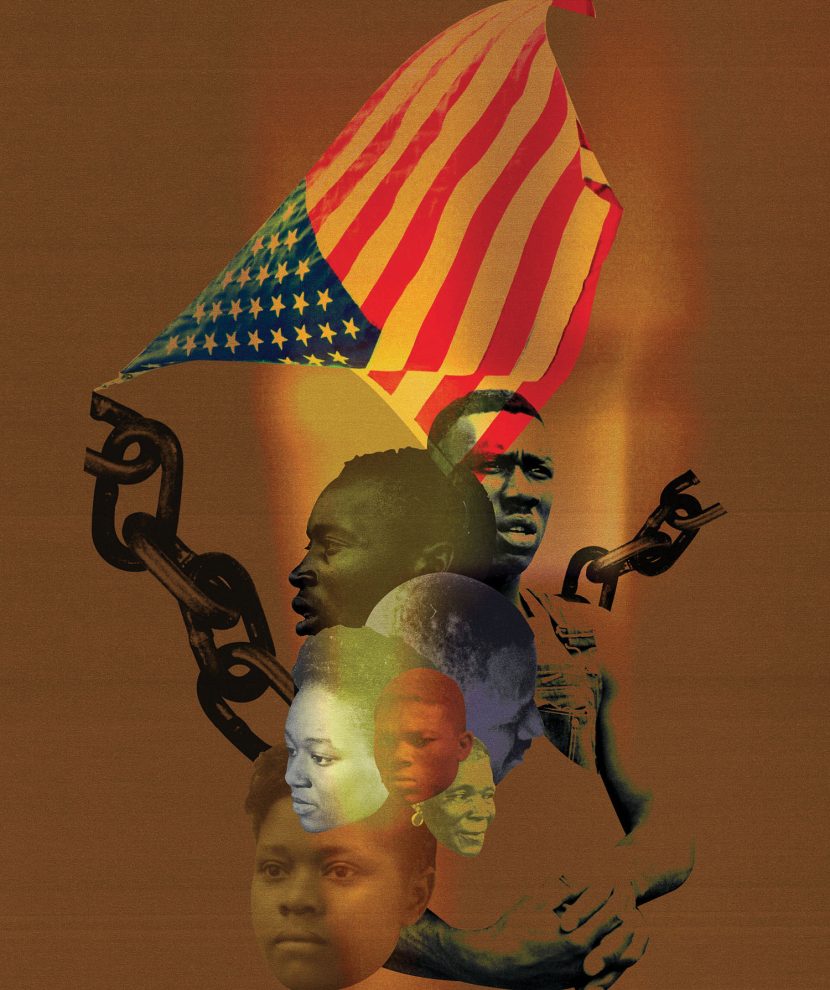

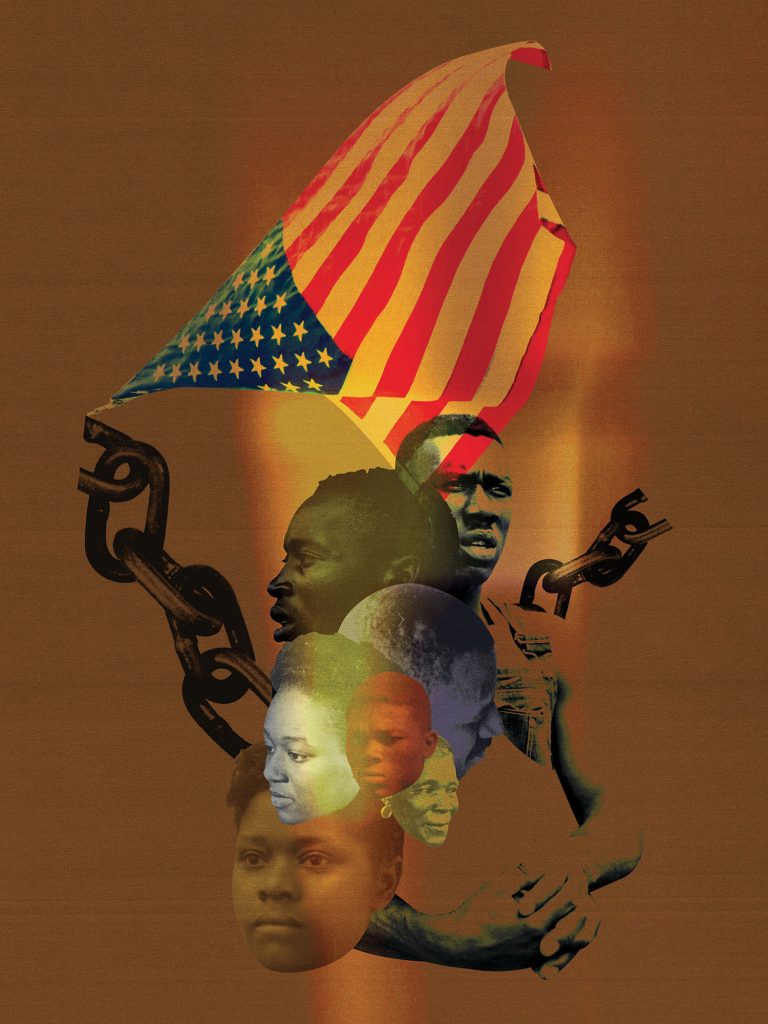

The question of whether and how multiracial participatory democracy can thrive in the United States is as old as the Constitution itself. For as long as the battles over who would be included and excluded from our political community have been fought, local government has been the front line.

When the Civil War ended in 1865, a brief window of political possibility opened across the conquered states of the Confederacy. In the half-decade remembered as Reconstruction, a coalition of newly enfranchised Black citizens, native southern unionists, and northern carpetbaggers rose to power in statehouses and local governments across the South. This “radical” coalition sought to reorder the political foundations of the former Confederacy.

Among the most utopian of the changes they implemented was replacing the old county system of local government with a system modeled on the New England town. The goal was to make space for multiracial democracy to take root and flourish at the local level. Briefly, it worked. In towns across the South, the multiracial “radical” coalition elected Black sheriffs, Black magistrates, and Black town clerks. These officials were the leading edge of an incipient shift in southern politics away from the plantation elite that upheld the system of slavery and toward a racially egalitarian new order.

This outraged the self-described white supremacists across the South, who sought to “redeem” their state and local governments from the hated radicals and return power to the white elite. These “Redeemers” developed an approach to local power and control that was intended to reestablish white supremacist rule. To ensure that white citizens were not subjected to what they called “negro rule,” they developed a Redemption Localism that consistently sought to limit local power, curtail local democracy, and defund or eliminate local services.

North Carolina is a representative example of how this story unfolded across the South. Once the Redeemers seized control of the state legislature there in 1874, they acted to wrest power away from the local governments that were still being governed by the multiracial coalition. Where they could, they dissolved local governments and offices. Where that wasn’t possible, they empowered the state legislature to wrest power from local officers. And when even that did not fully mute the power of emancipated citizens, they defunded local AND state services on the logic that no government was better than being ruled by the radicals.

Redemption Localism was a reactionary political project and overtly committed to establishing white supremacy. And yet, as I argue in a recent article, they were a precursor to, not an example of, Jim Crow. The Redeemers’ limit on local power was an important part of their strategy to slowly seize and consolidate power. Still, it was not until the turn of the 20th Century that they were able to fully dominate state and local politics and violently impose the systemic apartheid of Jim Crow.

Redemption Localism shows how the Redeemers manipulated the balance between local and state power to protect their political power and further the goal of white supremacy. This attitude towards localism remains familiar today, as the tools and structures of local power are manipulated to suppress Black voting power, dilute the voices of multiracial local democracies, and maintain existing distributions of power, wealth, and privilege.

Adapted from “Redemption Localism” (North Carolina Law Review, 2022).